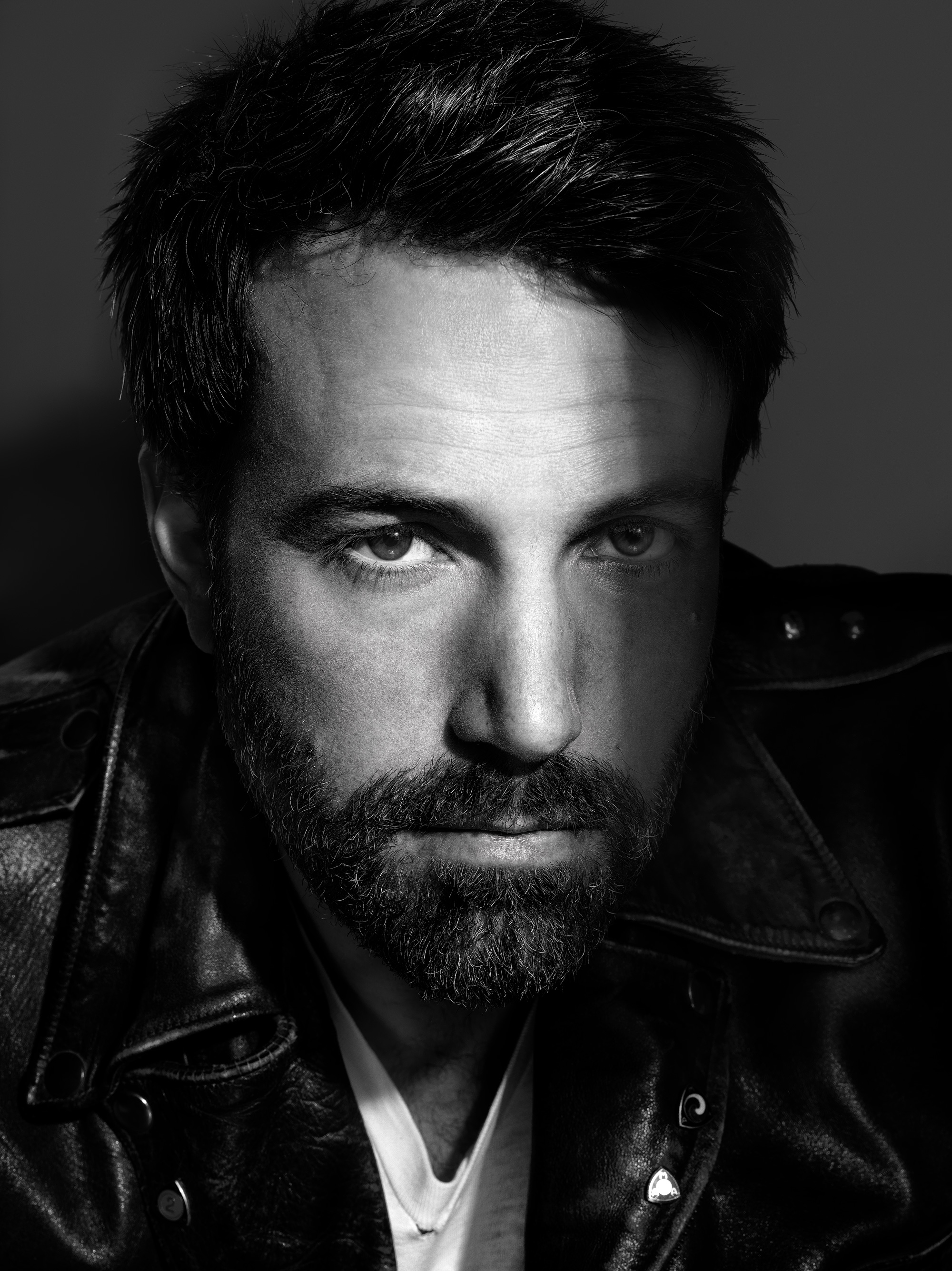

Ben Affleck

You say, ‘I really want to do this,’ and some grown-up gives you this disapproving frown and acts like you’re being irresponsible. But for this movie, I just kind of went crazy.Ben Affleck

Ben Affleck’s new film, Argo, is based on the true story of a special-ops mission known as the Canadian Caper that took place during the Iran hostage crisis of 1979, when 53 Americans were held captive by the Islamist theocracy of Ayatollah Khomeini. The plan—engineered to save six diplomats hiding out in Tehran—involved convincing Iranian authorities that the group of U.S. emissaries were actually part of a Canadian film crew scouting locations for a fictitious sci-fi epic in the mold of Star Wars (1977). Affleck, who directed Argo, also stars in the film as Tony Mendez, the CIA officer who came up with the audacious scheme. But “audacious” is also a good way to describe Affleck’s growing body of work as a filmmaker, which began with a 16-minute 1993 short called I Killed My Lesbian Wife, Hung Her on a Meathook, and Now I Have a Three-Picture Deal at Disney, and, in addition to Argo, includes the 2007 crime drama Gone Baby Gone and the 2010 heist thriller The Town.

All three of Affleck’s features are, in many ways, genre-busters—heavily plotted tales drawn into nuanced character studies. He has also shown himself to have a deft hand when it comes to casting, and some of the performances that he has elicited have been both vivid and complicated: Amy Ryan earned Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations for her portrayal of the neglectful mother of a missing 4-year-old girl in Gone Baby Gone; and Jeremy Renner received a supporting Oscar nod for his work as a twitchy, angry, but fiercely loyal career criminal in The Town. But while Gone Baby Gone and The Town told small stories based on hard-boiled crime novels (the former by Dennis Lehane, the latter by Chuck Hogan) and are set in rough neighborhoods in Affleck’s own hometown of Boston (Gone Baby Gone in Dorchester, The Town in Charlestown), Argo is a more wide-screen affair, portraying a series of historical events with far-reaching implications that took place against the backdrop of the powder-keg international political climate of the late 1970s—with a little Hollywood thrown in for good measure.

Gus Van Sant, who directed Affleck in Good Will Hunting (1997), recently spoke with the 40-year-old actor-director in Los Angeles.

GUS VAN SANT: I was conscious of the whole escapade in history that Argo is based on—that the Americans had gotten out of Iran by some means—but I don’t remember hearing about this story. Was it a secret?

BEN AFFLECK: Well, the movie is about kind of a sub-story in the larger drama of all the hostages and the whole takeover—Argo is just one small piece of that. The story itself was in Time magazine and is actually pretty well documented, but overall, it got kind of upstaged by the larger issue of the hostages. This incident in Argo happened on, like, Day 78 [The diplomats ultimately left Iran on Day 86], but it was on Day 444 that the hostages were released, so the events that we focus on in the movie were like this glimmer of hope that quickly subsided into the general malaise and depression about the fact that we had these people stuck over there and we couldn’t do anything about it.

VAN SANT: Somebody who watched Argo with me mentioned how implausible it was to hide under the cover of a supposed film scout. Then I just thought, No, that’s so perfect because it is implausible. The Iranian military guys would just say, “No one would ever try this, so this must be real.”

AFFLECK: People ascribe a certain kind of silliness to the movie business. Everybody feels like, “In the movies, they do crazy stuff.” So I don’t think audiences would buy it if it weren’t a true story. You’d just think, Oh, this is absurd. But to me, Argo is about storytelling, and in particular, the way fantasy touches a certain place in our collective consciousness. I like the incongruity of how in Iran, these people we think of as being revolutionaries or fanatics or whatever are just as aware of Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader as our people are back home.

VAN SANT: It was completely plausible right at that moment, with Star Wars being this international hit, that people would be trying to make the next Star Wars.

AFFLECK: The first Star Wars movie had come out in 1977 and had become this huge phenomenon with all the toys and everything—it just kind of swept America. But internationally, it was also a big deal. Sci-fi was something that everyone was aware of—it was a shared assumption that those mythologies were what people were making movies about. These tough Islamist revolutionary guards would imagine these fantasy stories, and the veil would come down. I like that a lot.

VAN SANT: It’s interesting because I think that George Lucas based a lot of the production design in Star Wars on places in Algeria and Tunisia and in that region.

AFFLECK: Yeah. In fact, I think they actually shot some of those movies in the Tunisian desert—at least some of the second unit stuff. That whole aesthetic of having these barren, dusty planets—the only place you could sort of go to get that stuff was in that region, so that was part of the whole thing.

VAN SANT: So did you actually go into Iran?

AFFLECK: No. I wanted to go—just for research—very badly. I really wanted to be accurate. The studio, however, said, “This is a bad idea,” to which I responded, “Well, I’m just going to go as a private person, without any association with the movie or the studio—just as a tourist.” Then I talked to the State Department about it, and they said, “Look, you could go, but there’s a likelihood that people from the government will show up with a camera, shake your hand, take pictures, and say, ‘See, this American supports what we’re doing.’ ” All of a sudden, a visit that’s supposed to be apolitical and personal could be publicized and create a headache for me and the movie. I wanted to feel like the brave, intrepid filmmaker who is not afraid, but then eventually it was like, “Maybe I am afraid a little bit.” [laughs]

VAN SANT: Whenever I hear about people going there, they always end up being followed by secret service agents.

AFFLECK: I tried to get this network of Persian filmmakers that I’ve met who worked and lived there to shoot stuff for me. That was so hard—people were so scared, and that was really telling. I wanted to get people to go in front of the former U.S. embassy building and shoot stills, but I couldn’t get anyone to do that. You know, even realizing how really Stalinist that country is . . . taking out any other religious ideology or anything else, it’s really totalitarian and oppressive. It was so interesting because the filmmakers who I talked to told me that there’s a guy who is the official censor. That’s his title. He stands by the monitor when you make your movie, and if the censor doesn’t like a line or doesn’t like what you’re shooting, he’ll just be like, “Don’t do that.” Talk about a studio interfering . . . [Van Sant laughs] Those guys can really dissuade you. You say, “I really want to do this,” and some grown-up gives you this disapproving frown and acts like you’re being irresponsible. But for this movie, I just kind of went crazy.

VAN SANT: How did you discover the material?

AFFLECK: There was a Wired magazine article that brought it to people’s attention. It was one that kind of circulated. You know how in Hollywood development executives and agents are always tracking everything? Like every article that comes out in Vanity Fair that everybody reads to see if there’s a movie in it. This was one of those things. The article came along and was sort of a you-couldn’t-believe-it-was-true kind of story. But is there a movie in it? Eight years before that, Tony Mendez’s book The Master of Disguise had come out, and the incident that this whole movie is based on basically comes from one chapter in that book. Those two things together were what we got the rights to initially, and they served as the basis for [screenwriter] Chris Terrio’s script.

VAN SANT: I was curious about the professionalism of the actual producers that were involved in the incident that you show in Argo. How was the Hollywood part of it handled?

AFFLECK: Really, the main Hollywood contact was John Chambers [played in the film by John Goodman]. If you ask any makeup artist, “Do you know who John Chambers is?” it’s like asking an actor if they’ve heard of Marlon Brando. Chambers won an Oscar for makeup, and was an incredibly accomplished, well-respected guy. He did the original Planet of the Apes [1968]. But he had also been working for a long time with the CIA. He had this double life—which, again, is one of those things that you wouldn’t believe if you just saw it in a movie. Throughout the ’70s, Chambers made masks and disguises used all over Southeast Asia, and was awarded the CIA’s highest civilian honor. So it’s interesting that there was this tension: Hollywood is so gossipy, with people trying to promote themselves all the time; and then the CIA is kind of the antithesis of that, wanting to keep everything secret and withhold information.

VAN SANT: So how many other people were taken hostage?

AFFLECK: In truth, there were something like 70 people who were initially taken hostage, but the story is a bit more complicated. Khomeini released some women to sort of demonstrate that the Iranians were humane, and they released a bunch of African-American hostages as sort of a propaganda move to say, “These people aren’t part of the imperialist government.” Then they kind of held on to the 50 or so people who were left until January 20th, 1981—the day that [Ronald] Reagan was sworn into office—and they were released.

VAN SANT: Wasn’t there a failed helicopter attempt?

AFFLECK: There was. They called it Operation Eagle Claw. To me, it seemed like an operation similar to the Osama bin Laden raid—a precursor to contemporary special-forces units for counterterrorism. It was actually really daring, and in some ways much more risky, because it didn’t just involve American troops, but also American citizens who were being held as hostages. They estimated that some hostages would be killed, so it was really a ballsy operation to order—and not the kind of thing that people usually associate with [then-U.S. President Jimmy] Carter. Of course, they canceled the mission. Then one of the helicopters crashed into a transport plane, which killed a bunch of soldiers, but they didn’t have time to get the bodies out. It’s an interesting political event, because if the operation works, you’re a genius, but if it fails, then it’s a terrible mistake. Basically, our movie takes place between the embassy being taken over and Operation Eagle Claw, which happened just a bit later.

VAN SANT: Here’s a filmmaking question: In general, when you’re working on movies—especially as the director—things are always getting out beyond your fingertips. You see something happening between takes and you’re always like, “Oh, let’s put that in.” Then, when you actually try to re-create it in order to film it, it doesn’t happen the way it did between takes. Is there any special way that you deal with that capturing-lightning-in-a-bottle aspect?

AFFLECK: What you just described is the story of my life. As soon as something good happens, everyone’s like, “Oh, that was cool!” Then you try to copy it in the next take and it’s no good anymore. But the stuff that just happens is always the best stuff in so many movies. Something is happening off camera, and you go, “That’s incredible! We should shoot that!” And then you turn around and shoot it and it doesn’t work. I’ve made capturing those moments the priority, particularly in a movie like Argo, where you have all these guests in a house together, and it’s not so much about what they say as it is about the sense that you get from participating in their conversation. That feeling becomes more what tells the story. If there’s an advantage that I have from being an actor, maybe it’s knowing on an intuitive level when to relax and take risks—becoming un-self-conscious helps foster the creation of those moments. For this movie, I just kept the camera running. I wanted to capture the kind of hesitation, or panic, about where to point the camera, so you kind of catch people in mid-sentence. I would tell the actors, “Do a couple versions with your dialogue, but then nobody say your lines. I don’t really care what happens.” I feel like that’s the best way to get something unexpected—that feels real. I remember actually learning some of that lesson from you when we were doing Good Will Hunting. It was a whole different kind of set environment than anything I had ever been a part of. Before that, I was just so used to this idea that you’re the student and the director is the teacher, and after you do your take, you go to the director and he says “B,” so you go back and change something and try and get a B+ grade. I don’t remember the scene—I think it was in a bar—and we’d done a second take and then we did a third. You just kept going, and I was like, Am I doing something wrong? I didn’t know how to define what was happening, so I went up to you and said, “Gus, what do you think?” And you kind of took a beat, and then said, “I don’t know. What do you think?” All of a sudden, I realized, “Oh, I get to think.” I felt so empowered . . . Maybe you created a monster.

VAN SANT: Yeah. [laughs] But on my shoots, the co-creators are invited to help, and I think that empowers everyone.

AFFLECK: I kind of ran with that lesson.

VAN SANT: The huge crowd scenes in Argo with thousands of extras were really exciting.

AFFLECK: Yeah, I would get excited about them, but it’s also one of those things that cost money. I was always suspicious that they were gonna skimp on me with the extras. There’ll be a big crowd riot scene at a student demonstration in the script, and then it’s just, like, 60 old Turkish guys. You go, “What’s going on here? Where are our extras?” Apparently, we weren’t paying enough money to get any young people. I’m like, “This is a student revolution, not a geriatric parade.” I was always rooting around the budget.

VAN SANT: Did you watch any films for stylistic research?

AFFLECK: It’s funny, because the period of time that the film is set in had this weird dichotomy where some of the greatest films ever, like Being There [1979], were being made right in tandem with some of the cheesiest sci-fi B-movie knockoffs. I watched all of those movies. Then, at the same time, I was watching things like Kramer vs. Kramer [1979], Ordinary People [1980], and Raging Bull [1980]—all these movies that were getting made right around then that were amazing. Cassavetes films like The Killing of a Chinese Bookie [1976] were also especially helpful for the California setting. For Iran, Missing [1982] was a movie from that era that inspired some of what I was doing. The CIA stuff, I wanted to feel like All the President’s Men [1976]—not the sexy CIA, but the CIA where papers are piled up on desks and there’s cigarette smoke everywhere. Bryan Cranston’s character in Argo is also a bit like the Ben Bradlee role played by Jason Robards in All the President’s Men. I thought that if what we did reminded people of movies from that era that were in the collective consciousness, then the subconscious would believe that our movie was actually taking place in the ’70s, so I stylistically adopted some of that stuff—but I kind of like that period anyway. I don’t know about you, but I like to just watch a bunch of movies. Maybe it makes me derivative.

VAN SANT: Depending on the project, I’ve definitely gone through using one, or two, or three movies as guideposts for what I’m thinking.

AFFLECK: Oh, good. That makes me feel like less of a hack if you do it, too. [laughs]

VAN SANT: So what are you going to do next?

AFFLECK: I’m gonna go act in this movie. It’s a really cool part—a smaller, sort of character-driven thing. It’s set in Puerto Rico, which will be hot, but nice. My family will come down and we’ll go to the beach . . . It’s so weird: You direct a movie, and it takes a year-plus of your life, so it seems odd to me now that I can go do three weeks on something and be done.

VAN SANT: Directors don’t have it that easy.

AFFLECK: No, actors have it easy like that, for sure.

Gus Van Sant is a Palme d’Or–winning director. His next film, Promised Land, will be released by Focus Features in December.