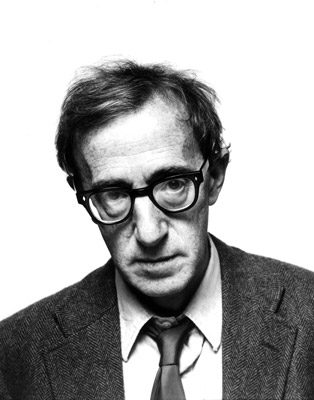

Woody Allen by Moonlight

Woody Allen returned to the theater this season with a contribution to the collaborative effort Relatively Speaking, a trio of one-act plays directed by John Turturro, and featuring, alongside Allen, works by Ethan Coen and Elaine May. Ari Graynor and Steve Guttenberg star as a new couple in Allen’s “Honeymoon Motel,” a wedding farce set in a purple and silk roadside pied-à-terre. The three stories that comprise the production are linked by theme. Like Allen’s, Coen’s and May’s comedies—”Talking Cure” and “George is Dead,” respectively—explore (and explode) the tensions, inadequacies, and absurdities of the family dynamic. Ironically, though, Relatively Speaking also considers the relationship between moral relativism and family dysfunction; the former emerges as a mere survival method, a way to escape a mess without cleaning it up. Of his own play’s pedagogical value, however, Allen is wryly self-effacing, insisting it isn’t his wisest work. On the heels of PBS’s evocative documentary on the auteur for its “American Masters” program, Allen answered our questions about his involvement in Relatively Speaking and his evolving relationship with the city he has, for many, defined. The result was an honest meditation on his city, his craft, and his life in between.

UZOAMAKA MADUKA: In films like Husbands and Wives (1992) or Manhattan (1979), the plots revolve around morally strong characters that provide an axis, a moral reference point, for the viewer. The Manhattan protagonist, Isaac Davis, is a good example—when he is accused of “thinking he’s God,” he responds that “he has to model himself off of somebody.” This moral axis seems to be absent from “Honeymoon Motel”; for the characters, ultimately, relativism reigns. Still, the emphasis on the tackiness of the room at the beginning of the play and the context of the honeymoon itself seem to undermine the characters’ conclusions. Is that an intentional critique or mere coincidence?

WOODY ALLEN: Please don’t judge anything by “Honeymoon Motel.” I wrote it quickly and only to make people laugh. There’s not a shred of purported wisdom in it, and if anything looks like it’s saying something, it’s pure accident. The emphasis on the tackiness of the room is a private joke between [scenic designer] Santo Loquasto and myself, as I believe he did a set that was even tackier than I had imagined.

MADUKA: And setting is your forte—in your various mediums, you have succeeded in establishing and evoking place, such that it often becomes a character itself. Have you always been quite sensitive to your physical surroundings?

ALLEN: I have always been sensitive to the places I’ve been filming in. There is something about big cities that turns me on, and for whatever mysterious reason, places like New York and Paris inspire me. I think it’s because cities represent civilization, and as crime-ridden and broken down as some of them are, it’s still better than skipping through a meadow.

MADUKA: The image of Paris in the rain often captivates your characters; it is again conjured in “Honeymoon Motel.” What is so seductive about Paris in the rain, and why has it become such a potent object for you and your characters?

ALLEN: Paris, like New York, is a city with endless possibilities, and to me, there is nothing like a big city in the rain. If I had it my way, it would be gray and rainy five days a week and bright and sunny two days. Think of a romantic interior: people dim the lights to make it more romantic; they don’t turn them up bright.

MADUKA: Midnight in Paris is in some ways an exploration of how the two worlds of fantasy and reality can co-exist, and how one can found that co-existence on either a fantastic escape or a bold leap. How would you define fantasy? When, if ever, is the bold leap into something fantastic not merely an escape?

ALLEN: Fantasy is only a state of mind that you can employ when existing in a real context. Fantasy is seductive and much more wonderful than reality, but you can’t take it to the bank. It’s always an escape. And if used as an escape, as in attending a movie or a show for a circumscribed period of time, it’s fine. When it starts to become undifferentiated from reality, it leads to big trouble.

MADUKA: “It’s always a question of high aims, grandiose dreams, great bravado and confidence, and great courage at the typewriter,” you once told Michiko Kakutani of your creative process, “and then, when I’m in the midst of finishing a picture and everything’s gone horribly wrong and I’ve reedited it and reshot it and tried to fix it, then it’s merely a struggle for survival. You’re happy only to be alive.” Your description of your creative process seems in many respects to echo your understanding of the world: how has the daily experience of your creative process conditioned your understanding of life itself?

ALLEN: My experience creatively is different than my experience in life, for, as my father would say, the simple reason that you can’t get hurt when everything goes wrong creatively. In life, you’re dealing with questions of mortality: it’s better to get sidetracked by your creative problems, your “second act” problems, than your real problems. Unfortunately, the real problems win out.

MADUKA: In “Honeymoon Motel,” the rabbi who officiates the wedding cuts an interesting character on stage, acting as both an authority and as a buffoon, yet never completely undermined. You have always been interested in the great existentialist thinkers like Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard, many of whom were men of faith. What, for you, is the relationship between faith, the search for meaning, and the specter of meaninglessness?

ALLEN: The search for meaning is irresistible, but everybody really knows deep down—and I mean really deep—that existence is meaningless, and the search has less odds of success than the Mega Ball lottery.

MADUKA: As a writer-director, it must be an odd experience to watch your work on stage when you haven’t yourself directed it. Is it frightening to relinquish control in this regard?

ALLEN: I don’t like relinquishing my work to another director. I was fortunate in being able to have John Turturro, but it was a one-act play, and it would be hard—if not impossible—for me to relinquish a full-length play or film script, no matter the director. I can’t imagine any director directing a screenplay of mine, because the great directors all have very personal styles, and the ones that don’t are not very interesting directors.

MADUKA: It seems that working in theater, you come into conversation not only with a group of artists, but with the place, the city itself. What characterizes the theater in New York, in your opinion, and how has that changed?

ALLEN: When I grew up, the Broadway theater towered in importance over films, and gradually over the years films grew up a certain amount. (I’m talking about American films, as foreign movies were always significant.) But the Broadway theater became less and less potent, and more and more of a trivial tourist attraction that’s vastly overpriced and needs star power to keep it going. This was not the way it was when I was younger: you could see Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, and even Eugene O’Neill productions.

MADUKA: I know you are a dedicated prose writer—is there a prose project you are working on at present?

ALLEN: I tried once to write a novel, which I found to be long and excruciating work, and I don’t think it came out very well, so I scrapped it. Maybe some day I’ll try again, but because I grew up uninterested in literature, a non-reader, I didn’t have any natural flair for it the way I did for show business—I grew up in the movie theaters.

MADUKA: You have given many people their image of Manhattan, and have, in the past, been one of its greatest cultural champions. But, of course, you’ve gone international in recent years. How has your feeling towards this city changed or matured? Does it continue to inspire you and your work? How has the city itself changed over the course of your career?

ALLEN: New York has changed for the better in some obvious ways, like the dropping of the crime rate and people don’t squeegee my windshield when I come to a stoplight. On the other hand, uncontrolled bike riders are a great hazard, and the wonderful idea of more and more people having bikes in New York will turn sour as people become alienated because so much of it is out of control. That will be a pity.

The city continues to inspire me and still remains head and shoulders above any city in the country. One problem for me is that I’ve grown older and I’ve had some success, and all those warmly lit townhouses and co-ops that I used to fantasize about, and dream about what was going on inside, I now know from my own experience. In one sense, I’m part of the establishment—and I don’t mind, except that it’s not as exciting as longing to become part of the establishment.

MADUKA: What is the most captivating part of your creative process?

ALLEN: The only parts that are captivating are beginning to write after you’ve gotten an idea for a film and putting in the music after you’ve shot the film and edited it together.

MADUKA: Has there been a recent time in your day-to-day life here in New York or elsewhere when you were greatly moved or captivated?

ALLEN: There is no vivid day-to-day experience apart from being moved by my wife and children, but I can’t think of anything in life that has moved me as much as the end of The Bicycle Thief.

MADUKA: And finally, what books are on your reading list now? Movies? Exhibitions?

ALLEN: Like everyone else, I very much enjoyed In The Garden of Beasts and a lesser-known book called Rules of Civility. And of course, [Diane] Keaton’s book. Living near all of the museums, my wife and I drop in frequently to all the exhibitions, and I get a kick out of most of them, but nothing ever equals just going to The Met and seeing the Impressionist paintings, particularly the streets of Paris painted by Pissarro. As far as movies go, as a moviemaker, I always find things I love in movies and things I don’t like very much, but my opinion is too prejudiced to be taken seriously.

RELATIVELY SPEAKING IS OPEN NOW AT THE BROOKS ATKINSON THEATRE. BUT YOU WANT MORE WOODY, SO YOU GO IN-DEPTH WITH ALLEN HERE.

PHOTO COURTESYSWIRC/MPA/RETNA LTD, USA