Stand Up For Your Rights

Six years ago, when I started work on two different gay biopics, Milk and Pedro, the lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transsexual, queer rights movement seemed to have followed in the footsteps of the black civil rights movement and the women’s movement— without their measures of success in obtaining anti-discrimination legislation. The movement had become corporate. There were only a handful of organizations that garnered much public attention, so the options for many potential young activists were limited. They could volunteer for or donate to these groups, but ultimately younger participants had little say when it came to strategies. Worse still, many of these groups had committed themselves to a make-no-waves, piecemeal-equality approach, preferring to remain settled in manicured, modern office buildings with its “leaders” rewarded with six-figure salaries.

I will never forget my first interview with activist Cleve Jones while doing research for my screenplay for Milk. After hours of sharing photos of demonstrations, blazing police cars, and brazen street theater in the 1970s, a flash of nostalgia and regret filled his eyes. “I can’t imagine what it must be like to be a part of your generation, Lance,” he said. “We had a real sense of purpose back then. We knew what we were here to do, and we knew how to fight for it.” His words felt true. My generation was the first in decades never drawn to activism in the streets.

Then, on November 4th, 2008, California voters approved Proposition 8, and for the first time, young people who had grown up with Will & Grace and Ellen, and who had been taught since birth that they were equal, were told their country considered them second-class citizens, and they were expected to take it. That kind of self-loathing just wasn’t in their bones.

When the dominant LGBTQ organizations took to the stages to shift blame away from themselves and plead for calm in the face of such discrimination, these young people refused. In Los Angeles, they literally marched away from these leaders, took over the streets, pounded on CNN’s windows, staged walkouts, kiss-ins, and gave birth to a new, strategically diverse, unapologetically aggressive grass-roots movement. And in doing so, they inspired the return of many of this movement’s greatest early leaders.

Back in 1973, Harvey Milk said something that’s become one of my favorite quotes: “Masturbation can be fun, but it does not take the place of the real thing. It is about time that the gay community stopped playing with itself and get down to the real thing.”

From long-time organizer David Mixner’s bold call for a march on Washington in May 2009, to fellow activists Jones and Robin McGehee’s answer to that call in the face of Congressional opposition later that year; from openly gay serviceman Dan Choi chaining himself to the White House in March and April, to the American Foundation For Equal Rights’ move to fight Prop 8 at the federal level, rejecting the self-loathing sentiments behind a piecemeal approach, it’s clear the gay movement is shifting back Milk’s way.

In short, the LGBTQ movement is doing what no other movement has previously done. It’s emerged from a corporate culture and given birth to a new grass roots. But how can this new energy be captured in images or words? Inherent in the term grass roots is the notion that there is no single leader or prevailing philosophy. Instead, there are thousands of voices with differing points of view and strategies, often speaking in opposition to one another and occasionally at each other’s throats. (Lord knows I’ve got the bite marks to prove it.) But it’s these disagreements that are making this movement strong again.

In a country as diverse as this one, it’s going to take a multitude of approaches and voices working concurrently and aggressively to win full equality in our lifetimes. And yes, I want to get married before I die, but more important than that, none of us want to see another LGBT kid grow up being told he or she is less of a person—or deserves fewer rights—than anyone else. So let me be clear, in no way do these profiles define the new grass roots. It would take an encyclopedia to do that. These are simply some of the new grass roots, representing thousands just like them, and hopefully inspiring more men and women to take singular stands or to form their own bottom-up organizations to take on city hall or the United States Supreme Court. Because the new gay movement isn’t playing with itself anymore. It’s after the real thing again. —DUSTIN LANCE BLACK

Rick Jacobs, Founder and Chair of the Courage Campaign

“I have always been passionate about social justice and politics, and I also always knew that I was gay,” says 52-year-old, Los Angeles-based Rick Jacobs. Growing up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, however, Jacobs did everything he could to suppress his sexual orientation, immersing himself into a career in finance, all the while keeping silent. It was presidential hopeful Howard Dean, and his unequivocal support of gay rights, who gave him the courage to politicize his identity. “The way I got into activism was when I met Howard Dean in the summer of 2002. By November of 2003, I quit my job to chair his campaign in California. I never went back.” In 2005, Jacobs decided it was time to bring this activism to a local level. “Every four years, California exports labor and capital for presidential races, but there is very little progressive infrastructure in California. I saw that energy and I said, ‘Let’s try to put something together.’ ” What transpired was the creation of the Courage Campaign, California’s member-driven, progressive online organizational hub that has made LGBT rights and outreach a priority. The campaign has trained 1,600 people in, as Jacobs puts it, “the public narrative story,” providing a forum for LGBT activists to verbalize and then mobilize with their experiences. Courage Campaign has just 13 employees and no office, but more than 750,000 members. “My essential guiding light is that I don’t want to live in any ghetto,” says Jacobs. “I want to live in America, and the hope that I have is that the next Rick Jacobs, growing up some other place where it isn’t yet comfortable to be gay, I hope that the work I’m doing will help him or her to understand that his or her sexual orientation is natural and that he or she can dream about marrying whoever they want to marry, can dream about being anything they want to be, and then go do it.” —ASHLEY SIMPSON

Chad Griffin, Board President of the American Foundation for Equal

Chad Griffin, the 37-year-old head of the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER), has no shortage of accolades. He was the youngest ever West Wing staffer (press assistant to the Clinton administration at age 19 in 1993), graduated from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in just three years, and has successfully led campaigns for issues ranging from clean energy to stem-cell research (which resulted in the passage of California’s Prop 71 in 2004). One cause that holds particular meaning to Griffin is the fight for full marriage equality. “When Prop 8 was overturned, it was one of the proudest and most joyous moments of my life,” says Griffin, whose organization assembled the legal team for Perry vs. Schwarzenegger, the case that brought down Prop 8. “In that moment, it was clear to me that so many lives were going to be impacted. It was real—those brilliant 136 pages of law and fact. It will go down in history as a turning point in this country.” Of course, the fight for full marriage equality isn’t over. AFER is currently fundraising, with the support of a powerful celebrity base, which includes Hilary Swank, Julianne Moore, Marisa Tomei, and J.J. Abrams, among others, for what Griffin refers to as “round two,” a Supreme Court hearing. “We won’t stop until there is full federal marriage equality in this country,” says Griffin. “It has never been convenient to give a minority their rights and there have always been those who suggest that the time is not right. It’s always taken a group of people to push the envelope. That’s what our team is doing.” —AS

Troy Williams, Executive Radio Producer and Activist

Growing up Mormon in Eugene, Oregon, Troy Williams led what he calls a “turbo righteous” existence. “I sublimated my sexuality into right-wing politics. I thought that God would somehow straighten me out,” says the 40-year-old Salt Lake City resident. “Thankfully, he ignored every single one of my prayers.” Today, Williams leads an equally active life on the opposite side of the political spectrum. He is the public affair director of station KRCL, which takes a very vocal role in Utah’s LGBT community, particularly the hour-long evening show that Williams executively produces, RadioActive, “which is dedicated to the ideal of ‘full spectrum social justice.’ ” He also organizes numerous LGBT rights events—such as February 2009’s Buttarspalooza, a celebratory protest/party that brought some much needed heat on Utah Republican state senator Chris Buttars after his now infamous gay–Muslim terrorist comparison. Williams’s approach to activism is multifaceted, and, as he’s happy to admit, “all over the map.” But if there’s one thing that ties Williams’s many actions together, it’s his militant commitment to ground-up activism: Williams embraces the idea of being a radical. “The goal with my RadioActive team is to inspire grassroots engagement within the community,” he says. As for Williams’s take on today’s national movement, “It’s bottom-up trajectories we need,” he says. “The radical in me isn’t satisfied with just access to marriage and military service. I want to see extraordinary social eruptions. I want to be the big, dangerous, scary queer the Christian right has been warning you about!” —AS

Alan Cumming, Actor and Activist

Alan Cumming was once described in The New York Observer as a “frolicky pansexual sex symbol for the new millennium,” a characterization which seems to indicate that his sexuality—both on-screen and off—is as much a part of his public persona as his work in film and theater. Cumming is something of a gay icon, but his activism started long before he became famous. “I come from Scotland, where we are brought up that we are encouraged to protest against any forms of injustice—and I genuinely believe that,” says the 45-year-old actor. “I’ve been politically active all my life. As I got more famous, I became more of a voice, because people listen.” But it wasn’t until he came to the United States that Cumming—who now lives in Manhattan—realized how disparate the rights of straight and homosexual citizens were. “I started to get really pissed-off that I was paying a lot of taxes in a foreign land and yet not being treated as a first-class citizen. That’s when I became more active with different organizations, and more vocal.” Perhaps because Cumming himself has been married to a woman and is currently to a man, he is able to articulate so clearly what seems to be at the center of this debate—that the gender of one’s partner has nothing to do with the rights one is entitled to. “For me, the whole thing is much more about civil rights,” Cumming explains. “It’s about the individual being treated in exactly the same way and having the rights and the protections of anyone else. It’s all very well us having nice words and being given affirmations from the president or whoever, but unless we have the same rights—the same legal rights—there’s no point in us having the conversation.” —LUCY SILBERMAN

Cleve Jones, AIDS and Equal Rights Activist

One of the founding fathers of the equal rights and AIDS advocacy movements, 56-year-old Cleve Jones has experienced a roller coaster of highs and lows in his 30-some years of activism. “The single most important day of my life was November 27, 1978, when Harvey Milk was assassinated,” says Jones, a close confident of the late San Francisco city supervisor. “I was there that day. I was one of the people who found his body. Everything that has happened to me since really goes back to that day.” What Jones is referring to is effectively the entire legacy of the gay rights movement, which Jones himself had a role in helping to build. A student at San Francisco State University at the time of Milk’s assassination, Jones dropped out to work as a legislative consultant. He went on to co-found the San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1983 and was responsible for the creation of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1987. Today, Jones remains active in the equal rights movement. He coordinated October 2009’s National Equality March and is currently working with “Sleep with the Right People,” a union campaign that encourages LGBT travelers to stay at hotels that treat their workers humanly. And while Jones was once skeptical of today’s gay rights movement, he is hopeful. “For the first time now, we’re really articulating the dream, and the dream is full equality in all matters governed by civil law. For decades, we fought state-by-state, county-by-county, city-by-city for fractions of equality, and now the movement is very clearly focused on winning equal justice under law in all matters governed by the law in all 50 states. Real change is possible.” —AS

Theresa Sparks, Public Official

Theresa Sparks served her country in Vietnam. She had been married with children. She started several successful businesses. She did all of these things as the straight, normal American man she was raised to be. In 1996, the Kansas native moved to San Francisco, where she began living as a transgender woman. “I transitioned in the mid-’90s. Prior to that, I had been CEO of several medium-size multinational corporations. After I transitioned I just assumed that my life would go on,” Sparks says. “I was unable to find employment for almost two years just due to discrimination. During that period of time I got involved with an activist group in San Francisco that was really focused on violence against LGBT people in the United States. We found statistics suggesting that three transgender people were being murdered every month. This had to stop.” Sparks threw herself into the political LGBT movement in San Francisco, working with and eventually becoming a leader of both the city’s Police Commission and Human Rights Commission. Now, at 61, she’s running for District 6 supervisor in San Francisco. The famous political activist, Harvey Milk, pushed the envelope for gay rights, and Sparks is carrying on the tradition, but her history—and visibility—as a transgender person is perhaps mending a rift within the gay community even the famous 1970s city supervisor could not. “You know, transgender people have been involved in this movement since day one,” she explains. “We’ve been at the front lines for a long time, and I think now, almost 50 years later, we’re being accepted as an equal partner. That’s very important for the movement and it’s certainly important for us.” —LS

Pam Spaulding, Blogger, pamshouseblend.com

Pam Spaulding didn’t set out to have one of the most popular blogs dedicated to gay civil rights, but pamshouseblend.com quickly went viral. “When I launched the blog in 2004, it was really just to personally vent about the state of the political situation at the time,” the 47-year-old North Carolina–based blogger says. “[George W.] Bush was up for reelection. I was seeing the level of rancor on the side of the religious right over LGBT rights. When I started, I wasn’t thinking about people reading my work.” Soon, Spaulding was serving on panels to speak about the discriminatory political landscape and guest blogging on sites like the Huffington Post. She became what she terms an “accidental activist,” with a blog that racks up almost 250,000 visitors a month. Part of the site’s draw is that it allows readers to submit diaries about what’s going on in their cities. “I think the Internet has given voice to people who are terribly frustrated, with feelings of isolation. Now they can go on and see what other people are doing by reading blogs like mine,” she says. Spaulding knows it’s not just people in the gay community trafficking her site. “The first time I was called by the White House communication over a year ago, I nearly dropped my phone,” she remembers. “The [White House is] reading the blog and responding to either criticism or praise that I have.” It would be easy for bloggers to hide in anonymity—especially when the government is watching—but Spaulding purposely uses her own name. “I feel like I have to speak for people who are unable to, just to show that you can do this,” she says. “I have a full-time day job. I can’t quit and just blog. I like to have more voices than silence. Everyone needs to speak.” —LS

Gavin Creel, Activist and co-founder of Broadway Impact

In 2008, Gavin Creel was interviewed about his role as the sexually and otherwise conflicted Claude in the Broadway revival of Hair, the classic ‘60s countercultural musical. The journalist asked Creel if there was anything about his character that he related to, professionally or personally. Creel admitted what he had long known—that he was gay—and, by coming out publicly, he embraced his role not only dramatically but also politically. “Hair woke up this great activism in me,” the 34-year-old Ohio native says. “I just thought, ‘We have the possibility to become the industry that is at the center of this movement. I don’t want to sit still anymore.’ ” Soon after his revelation, he helped form Broadway Impact, an organization composed of men and women who work in the theater community and are dedicated to the support of marriage equality. They started their mobilizing effort by attending Prop 8 protest rallies; within two months, Creel and his co-founders, Rory O’Malley and Jenny Kanelos, had a full-on grassroots organization. “We were like, ‘Let’s teach people how the government works,’ ” Creel explains. “As I got older, I realized the power we have in electing these people [as] our representatives is everything—our vote is everything. They’re only elected to do what we tell them to do. With Broadway Impact, as we learn, we’re going to share the information and we’re going to try to fire people up.” Broadway Impact utilizes its talented supporters to raise awareness through performances by Broadway casts, rallies, and fundraisers for other pro-equal-rights organizations. “All I want in my lifetime is the law. I want the law and the rights in pen, in the books, case closed,” Creel says. “That’s what I’m fighting for. People aren’t going to see me as equal until the law of the land declares me as equal.” —LS

Constance McMillen, Teen Activist

Constance McMillen did not ruin the prom. But she did ruffle feathers in her conservative hometown of Fulton, Mississippi, after the ACLU sued the city’s public school district on her behalf. McMillen had been told, in no uncertain terms, that while she could attend the prom with her girlfriend, they could not arrive together, slow dance, or do anything else to indicate they were a same-sex couple. McMillen’s case made national headlines earlier this year, but it only came to light because she advocated for another classmate who had faced discrimination. “There was a boy who dressed in feminine clothing, and my school told him that he could not come to school like that,” she says. “I called the ACLU. I told them about him, and I told them my story. They were like, ‘Well, they can’t do that to you, either.’ That’s really how the whole thing started.” The “whole thing” included a canceled prom (a response to the lawsuit), a separate “formal dance party” (read: prom) to which McMillen was not invited, a fake prom held especially for her (and attended by only seven other students), and attention—both positive and negative—from people on both sides of the debate. McMillen was awarded $35,000 in the case, which also resulted in the school district adopting a policy forbidding discrimination or harassment based on gender identity or sexual orientation—the first of its kind implemented by a public school in the state. “I’m completely full of hope, because if I weren’t, I would be one of those sad gay people who are like, ‘It’s sad to be gay because we’re discriminated against,’” the 18-year-old says. “I’m the opposite. Like, ‘You’re discriminated against? Let’s do something about it.’” —LS

Alan Bounville & Iana DiBona, Activists, Queer Rising

Sometimes words aren’t enough. Sometimes you need to chain yourself to the entrance of a New York City marriage bureau to protest marriage inequality, or crash a former state senator’s Christmas party to let him know his voting record matters to you. Alan Bounville and his group, Queer Rising, believe actions speak louder than words (although they use those too—often loudly). Since 2009, the New York City–based, 20-strong organization has been engaging in acts of civil disobedience all over the country. “It’s the people rising up and saying, ‘I’m no longer willing to wait for what is rightfully mine, my equality,’ ” 34-year-old Bounville explains. “In order to speed things up, I have to get involved and jam up the system as consistently as possible. And I need to work with people to build that part of our movement.” Though he had come out years before, Bounville’s activism really started in 2008, when he was still living in his native Florida, where voters passed the equivalent to Prop 8, a measure which defined marriage as being between one man and one woman. “I had talked to my family about it and said, ‘Please vote no on this amendment.’ They dodged the subject,” he says. “I never thought my family would vote against my equal rights, but that’s exactly what happened. It woke me up.” Bounville left Florida, co-founded Queer Rising, and engaged in direct-action activism, which has resulted in a lot of attention (and a couple of trips to jail). Iana DiBona, a lead organizer for Queer Rising, sums up the group’s mission succinctly. “People have to understand that their individual voices are being heard the more that they go out there and push for their equality,” she says. “We all want the same things. We all want to be equal.” —LS

Dan Choi, Face of the Movement to Repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”

Growing up as the gay son of two Korean immigrants in Orange County, California, Dan Choi, now the most prominent face of the movement to repeal “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” never planned on coming out. “My parents were very conservative, very religious,” Choi says. Silence was assumed over the years as he became a student at the United States Military Academy at West Point and then a soldier in the U.S. National Guard. It was Choi’s proximity to death—and love—that changed everything. “I served in Iraq. A lot of people in my unit never came back alive,” Choi says about his time at war in 2006. “All of a sudden, life was so short, so unstable. I thought to myself, ‘I could die at any moment. Why am I hiding this part of my life?’ ” So, when Choi returned to the States after his tour, he started his first relationship. Then, he started talking. He told his friends, his comrades, and his father. In a March 2009 interview that shocked the nation, he even told Rachel Maddow live on her show. “That was civil disobedience,” says Choi. “Coming out shouldn’t be called civil disobedience. It should just be telling the truth. But the fact of the matter is we’re not there yet.” Since entering the public eye, the 29-year-old Choi’s voice has only gotten louder. He chained himself to the White House twice this past spring, took part in a seven-day hunger strike last May to send a message to the Obama administration, and spoke out at numerous LGBT rights events, including October 2009’s National Equality March in Washington D.C. “You can talk all day and make legislative agendas and give a lot of money—and we have—to trying to get this bill through Congress, but the greatest effect is just people coming out and committing to civil disobedience,” says Choi. —AS

Robin McGehee & Kip Williams, Co-Founders of Get Equal

Northern California residents Kip Williams, 28, and Robin McGehee, 37, believe in the power of direct action. They met in the spring of 2009 while organizing responses to Prop 8 and were recruited by Cleve Jones to help develop the highly publicized National Equality March, which drew an estimated 200,000 individuals in Washington D.C. It was clear that the two shared similar philosophies of activism. “In doing all the organizing for the March, one thing stood out,” says McGehee. “There is such an undercurrent of frustration, and not only for LGBT people, but straight people, who just think, This is so stupid! Enough is enough.” Williams agrees: “There aren’t fractions of equality. Every now and then, the government passes something to us and says, ‘Here you go. Now be quiet for a while.’ That’s not enough.” After the success of 2009’s March, the two converted their feelings of anger and urgency into further action. They founded Get Equal in March 2010, an LGBT rights organization that utilizes direct action to push for equal rights. “We’re just trying to apply more pressure than other organizations,” Williams says. The group’s tactics include leaving combat boots in the offices of Virginia Democrat Senator Jim Webb as a result of his response to his support of “Don’t ask, don’t tell” this past September. Among the core issues for both Williams and McGehee are federal protection for LGBT employees and repealing “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” The greater goal, however, is one of dignity and outreach. “There are so many people that live, in their opinion, undignified lives, because they’re afraid to be honest,” shares McGehee, “In the end, if you can give those people a little bit more pride and a little bit more courage, everything that you’re doing is worth it.” —AS

Cynthia Nixon, Actress and Representative of Fight Back New York

Cynthia Nixon is not Miranda Hobbes, but they do have something in common: They’re both tough-as-nails New Yorkers, dedicated to equal rights. In recent years, the actress, perhaps best known for her role on Sex and the City, has made an equally impressive turn as an outspoken voice in the gay community. Since coming out in 2004, Nixon, 44, has lent her celebrity to Cyndi Lauper’s Give a Damn Campaign and True Colors Fund (among other important causes), and to Fight Back New York, an organization dedicated solely to ousting anti-equality New York senators, both Democrat and Republican. “We’re literally going after people here,” Nixon explains. “You voted against our rights? We’re going to let people know about that, and the other heinous things in your record. You’ve gone after us, we’re going after you.” Fight Back can be credited at least in part with the recent defeat of Buffalo’s Democratic state senator Bill Stachowski, having spent $130,000 to raise awareness about his anti-equality platform. “I sat in his office and said, ‘This is so important to me and my family and my girlfriend and our kids.’ And he said, ‘Yeah . . . it doesn’t feel right to me,’ ” Nixon recalls. “That’s the really frustrating thing— people who are against it actually don’t have an argument. It was exciting to watch him go down, and to know we were a large part of that.” Equally gratifying was hearing newscasters discuss the senator’s loss, specifically mentioning his opposition to gay rights. Nixon and Fight Back are working toward ending discrimination in New York, but their mission is part of a national dialogue. “The days of the closet and being treated by the law as second-class citizens are waning,” she says. “As we like to say at Fight Back, ‘We tried the carrot and now it’s time for the stick.’ ” —LS

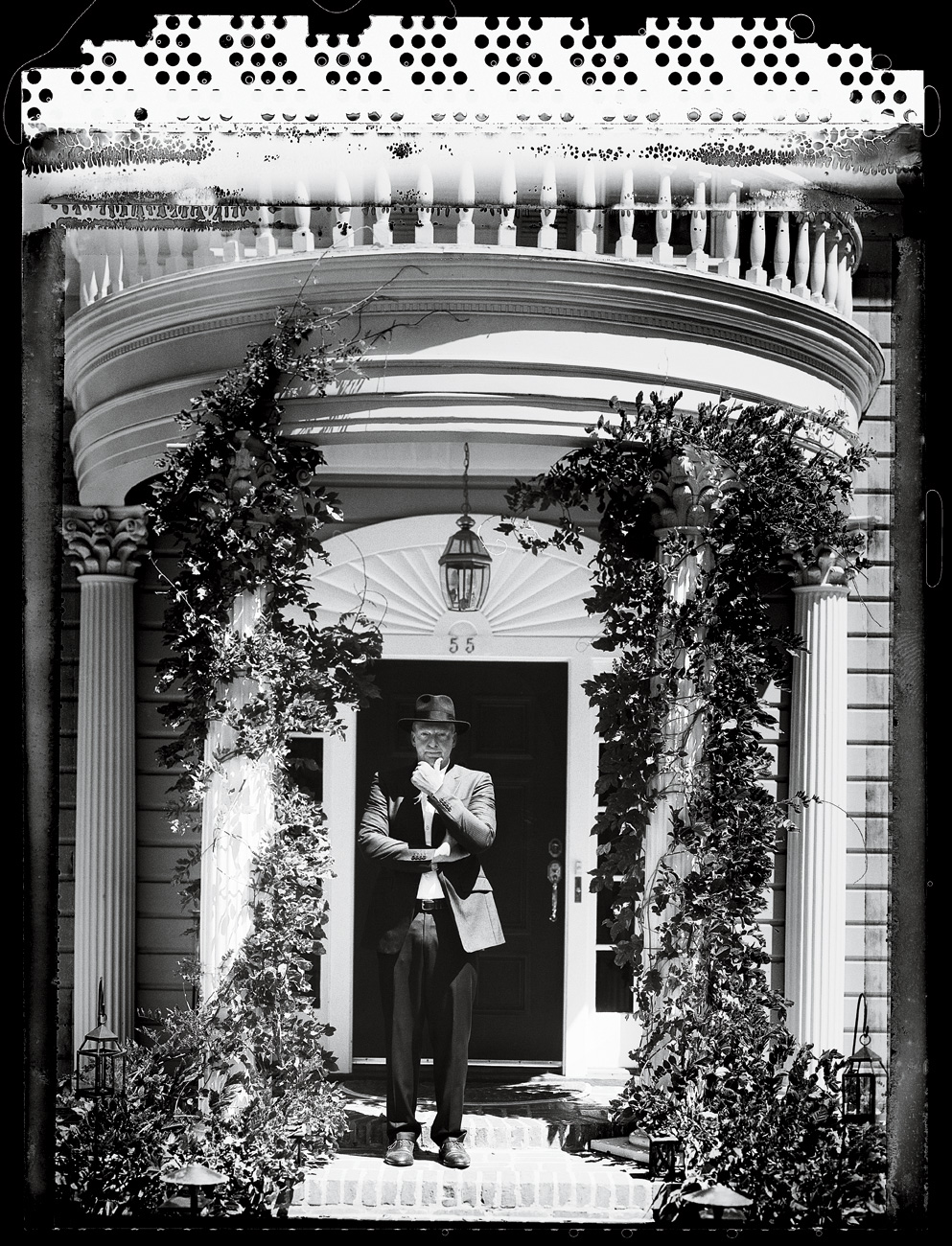

David Mixner, Activist, Organizer, and Writer

“I’d describe myself as a homosexual whooping crane,” says David Mixner, who, at 64, is a surviving member of a generation of gay men who weathered the 1980s AIDS epidemic. “We are in a community absent of men getting older.” At the height of the civil rights struggle, Mixner began a 50-year career in organizing and activism, rallying city workers to unionize; assembling students to protest the Vietnam War; and later spearheading several progressive political campaigns. But it wasn’t until the mid-’70s that Mixner, then 30 and living in California, became a gay rights activist—and admitted who he was to the world. “Anita Bryant came to California to launch a campaign to make it against the law for homosexuals to become school teachers,” he says of 1978’s Proposition 6, to which he mobilized oppositional voices. “I knew if I did that, I’d have to come out. So Anita Bryant brought me out of the closet.” Mixner helped found the Municipal Elections Committee of Los Angeles (MECLA, the nation’s first gay and lesbian political action committee) when politicians he’d long known rejected fund raising efforts. The AIDS crisis further inspired his gay rights activism. Mixner estimates that he lost 300 friends— including his longtime partner—to the disease (“I did ninety eulogies in two years”). At a liberal dinner party in the ’80s, Mixner and his partner were served on paper plates, while everyone else ate off of china. “You say, ‘Do we stay here and raise money, and suffer through this humiliation, or do we walk out?” he recalls. “Of course we stayed. We had to.” Mixner has since produced bestselling books, plays, and a heavily trafficked blog, davidmixner.com, dedicated to promoting equality. “I want to live one day—just one, I’m not greedy—as a free man,” Mixner says. “I would just love to know what that’s like.” —LS