New Again: Remembering Helen Gurley Brown

Long before Sex and the City, Helen Gurley Brown’s book Sex and the Single Girl (1962) broached and encouraged the subject of pre-marital sex. “Nice girls do have affairs, and they do not necessarily die of them,” Gurley Brown insisted in her bestseller. Certainly a shocking statement in the pre-swinging 1960s, and, alas, something that might still shock many Americans today. Brown’s first book did not entirely shatter gender norms—Sex and the Single Girl expects all women to strive for physical desirability and assumes that their end goal is still to marry “Mr. Right”—but it’s role in the post-war women’s movement in undeniable. Men could have their Playboy fantasies and dalliances before marriage, but so could women.

Three years later, in 1965, Brown became editor in chief of Cosmopolitan and maintained a relationship with the magazine until her death on Monday at the age of 90.

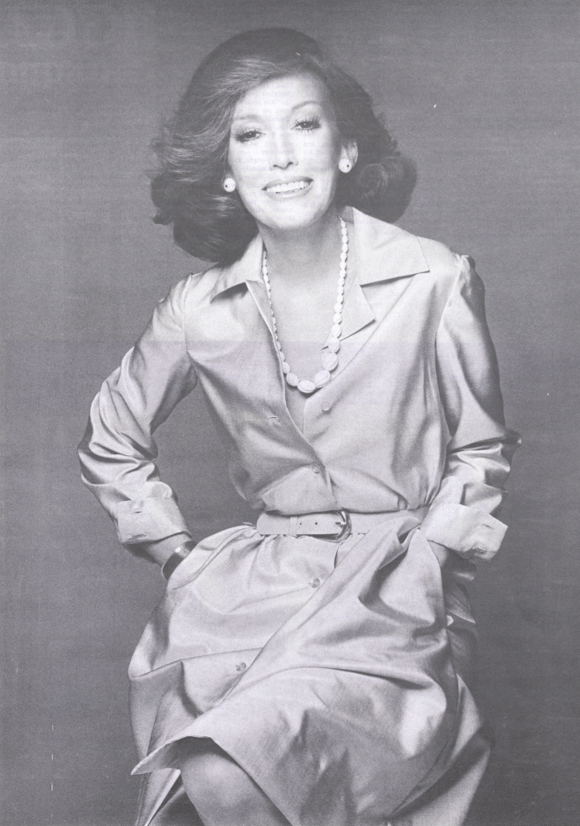

Interview spoke with Brown in 1973. In the interview, which we have reprinted below, Brown talks frankly about her opinions on cosmetics, beauty, and how to “become someone”—the controversial Cosmo girl take on female liberation.

That Cosmopolitan Girl

by Robert Colacello

Helen Gurley Brown speaks softly and carries a big stick. Sitting demurely in her very feminine office decorated House and Garden style, high above West 57th Street, she sweetly beckons Interview to come a little closer on the loveseat, the better to appreciate her soft sonorous whispers. “By the end of the year we’ll have 13 editions: England, Australia, Germany, France, Italy, Mexico, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Peru, Colombia, Central America…” she purrs.

ROBERT COLACELLO: Before we discuss the magazine, I’d like to know a bit about your background.

HELEN GURLEY BROWN: Well, it seems like such a threadbare story by now I’ve told it so often, but I’ll tell it again because it is so essential to understanding me and the magazine. I grew up in Arkansas, in the Ozarks. My family wasn’t as poor as the others around us—they didn’t have food to eat, shoes to wear—we weren’t that bad off, but still it was a difficult struggle. My father died when I was 10; my sister got polio a couple of years later and was paralyzed. So there I was—my sister in a wheel chair, my father gone, and my mother a quiet little mouse. You see, it was the ’30s in the South, so my mother was not prepared to cope. So I was scared to death. And being that scared, everything afterward became a struggle not to go down the drain. Struggling became a way of life for me.

You know, I think I’m a fairly average person, I think I have only a medium IQ. I didn’t go to college, obviously. I had no emotional support from anybody. So the first thing is I guess I’m a survivor. There are many of us survivors and any successful woman of my age has somewhat of that in her. Now it’s somewhat easier for a woman to be a film producer or something like that if she wants, though it’s not that easy. But to be any kind of successful woman took a lot of doing in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s… in the ’70s it’s getting simpler. So my own credo has been to marshal everything I had, which I don’t think is considerable, just a few little things, and I got them all together and kept on struggling and working and being scared and one thing led to another.

But I didn’t really come into my own until I was 40, 10 years ago, when I wrote a book, Sex and the Single Girl, that was a bestseller. And then we started at Cosmopolitan and that has been so bloody successful. I’ve just been so lucky. I don’t know if you’re really able to take advantage of your full potential until you’re older. There are a few people who are incredibly gifted and make it when they are very young, but I didn’t. With women it takes longer. You just keep working and when you finally get it, it feels very, very nice.

COLACELLO: It seems to me that the Hearst Corporation made a very wise move making you editor of Cosmo. How did that happen? Was there one person in particular who was clever enough to recognize your talents?

GURLEY BROWN: Well, it was Richard Deems, head of the magazine division, who gave me the job. You see, after I published Sex and the Single Girl, I had a syndicated newspaper column called “Women Alone” and we used to get sacks of mail from women who wanted advice, because at the time there was no Sensuous Man or Woman, no Dr. Reuben, no Joy of Sex, nothing to tell anyone anything. And here was this reasonable sophisticated woman—me—who had been there, and women seemed to feel that they could write to me and get the straight scoop, whereas if they wrote to Abigail or Ann Landers they just got Mother, Home, and Bible, which didn’t do them any good if they were pregnant or dating a married man they didn’t want to give up.

So I was going mad answering all these letters and my husband said, you ought to have a magazine—it would be a natural. So we sat down one night and developed a format—just a few typed pages—of what such a magazine would be like. I thought up a couple hundred article ideas—all the ideas that had been rejected when I was at an ad agency before the book. And we took this little format to Fawcett and Dell Publishing and a couple of other places, but they didn’t want a new magazine because it’s a very difficult thing to do—it takes a lot of money and guts. But finally it got into the hands of the Hearst people, and Cosmo was doing so badly, they were just about to fold up, and I think they figured they didn’t have a whole lot to lose.

But, you know, there are not that many people who know how to edit. It’s a funny tiny little obscure talent but it’s very special. You have to have the feeling of popular taste. You can do something glorious but there are not that many glorious people out there to buy it. So I just happened to have this talent for editing. They looked at the format and thought I had it. But Hearst was severely criticized. A lot of people canceled their advertising, including Coca-Cola and AT&T and others, because I was considered quite scarlet at the time (1964). Now I’m like Billy Graham, I’m so proper compared to everyone else. But at that time Hearst was quite gutsy to let me do it.

The first issue, all my stuff was in sold over a million copies. They had sold 700,000 the month before. We’re selling now about a million seven. Only two or three others do as well as we do: Playboy, TV Guide, The National Enquirer. We passed up all the women’s magazines, and we raised the price four times. It was 35¢ when I got here; we raised it to 50¢, 65¢, 75¢, and now it’s one dollar. But it’s not how many issues you sell, McCall’s sells eight million but they lose money—maybe they’re finally in the black now. But if I’m considered a hotshot, it’s because what we do works. Makes money. My theory is that people never get tired of looking at beautiful pictures of gorgeous girls.

COLACELLO: I think people are hungry for glamour, not only in magazines, but in entertainment too.

GURLEY BROWN: Of course. I don’t think people want to go and suffer. I think it’s alright to go and cry. I saw Seesaw for a third time the other night. If I like something I see it three, five, eight times, I saw Follies seven times, Night Music three and I’m going again—but here I was at Seesaw crying like a baby. My eyelashes came off as usual. That’s okay, that’s pleasurable, but to go and suffer, that’s something else again. I just think that in the theater, in movies, in magazines everything should be gorgeous.

COLACELLO: But girls must buy Cosmo because they think they can look like the cover girl if they really work at it. It gives them a standard to live up to, no?

GURLEY BROWN: Sometimes I wonder if I’m doing everyone a disservice by perpetuating the idea that beautiful is better than plain, because having done everything just about that you can do, sparing no expense, and not effort, to become better looking, I know that only so much can be done. You start with certain bone structure and certain body structure. And I sometimes think, am I really terribly out of it and unfair to be pushing young women to be something that they may not be able to become, i.e. a living raving gorgeous doll, i.e. Lois Chiles. But I can’t feel that it’s not better to try, because within the trying you get something out of it. It makes you feel good. You know, every morning when I’m thrashing around on the floor doing my solid hour of heavy exercises I’m not really doing that for anyone but myself. It makes me feel good. And it’s true, with all this pounding and pummeling and torture I have only got my hips down from 39 to 36 and there is no way I’m ever going to get down to a 35 or a 24 which would be nifty because I have a 23 inch waist. Even so I’m sure I’m a great deal better off than if I weren’t doing it. So I must really emphasize that I believe what I’m talking about. I believe what I’m doing. I think it is still viable in 1973.

I’m watching all the time to see if the stuff that I’m promoting is still where it’s at. For example, if men and women, and women and women, and men and men can communicate, if they begin to get where they’re all having a great time together, then I think Cosmo would be a bit passé because we deal with problems for the most part. And if there comes a time when you really are thought to be beautiful and wantable and desirable and attractive and lovable and longed for just by looking like a Dutch Cleanser can, okay, I will be out of date, and will do something else. But now, for the moment, I still think pretty is better and you can get a certain distance with pretty that you couldn’t get if you hadn’t tried. Anyone can have teeth fixed and noses taken care of and hair worked on. Like Way Bandy. I don’t know if people think he’s insane or not. He’s the most honest man I know because he frankly admits that he has a touch of silicone, and he uses some makeup, and he tweezes his eyebrows, and Way Bandy is gorgeous. But I only use him as an example because he is so outspoken about it. Nearly everyone else keeps it a secret. Like I have very fragile hair and I go to Dr. Orentreich once a month for injections, and that place is wall to wall people. A lot of them are famous, but of course he ushers them right in and out. But do you think any of these people will admit what they are having done? That’s why I give Way credit. You know, you just can’t operate if you feel that you look funny. And a lot of it is how you feel about yourself. If you’re doing everything you can to feel attractive then that’s enough to get you by.

That’s why I think people are going to be silly if they ever attack the cosmetic industry in terms of labeling everything that goes into the products, you know, truth, truth, truth. Because that isn’t why you buy cosmetics. You don’t buy them because they are going to have any intense medical effect. If they did the FDA wouldn’t let them on the market in the first place. So we’re using a lot of different things because it feels good to do it. It’s sensual, it makes you feel okay. That’s basically what I’m all about. Yes, you ought to be beloved because you get up in the morning and you’re Bob or Helen or Carol or Ted or Alice or whoever. That ought to be enough. Well, it’s not. But that’s only half of it. That’s how you look, the other half is who you are. Being somebody is better than not being somebody vis à vis what you want out of life. If you want to talk to interesting people and have them talk to you, and if you want enough money to live someplace pleasant and to go on trips and be able to help people you love, you simply have to get it together and be somebody. And I think all the kids see now that the protest thing just isn’t enough. It’s okay to protest a bad thing, to march, but it’s not the same as achieving. So that’s the other half of Cosmo. We say, whatever it is, try and do it the best you can. Get on with it, it’s more fun that way.

You see, I’m a very shallow woman. Having had such a rough beginning, I’m still busy keeping it together for me, as it were. So I’m rather self-centered and subjective and all I could tell people are the things that worked for me. I don’t know if I’ll ever be involved in a cause that is bigger than self-improvement and self-realization. There are some bigger and better causes and some wonderful people are leaders in those causes. They become politicians or philosophers or anthropologists, but so far I’m only able to say to my girl, I’ve been there, I know what it’s like, and I will tell you about it and help you. The other night I went to Cleveland Amory’s benefit for the Annual Fund at the Uris Theater and that’s the first philanthropic thing I can remember doing for ages. I try and be kind and not hurt people and to make people happier, but in terms of some outside cause, outside of Cosmopolitan, away from me, me, me, that’s the first thing I’ve done in weeks. It seemed so strange. I’m not a do-gooder… you’re a very good listener. You just listen and listen and one talks on and on.

COLACELLO: Okay, here’s a question. How do you select the covergirls?

BROWN: Well in the beginning I just had the idea that all the covergirls should be gorgeous, and not just interesting, not beautiful in an offbeat or exotic way, just plain yummy gorgeous. The first year I was here, several different photographers tried covers for us, but during the second year I discovered Francesco Scavullo or he discovered us and no one else has really done a cover since with one or two exceptions. The reason is that I don’t know what it is he’s got but it’s some kind of magic, he just gets that yummy yummy beautiful look out of people. They just seem to glow. Many other people have tried but it just doesn’t work for them. Of course, Scavullo cares passionately about his work—he takes so many cover shootings and we only use one, he always photographs beyond the cause. He picks the girls he thinks would be right and then we decide if we’re going to use them. Because I can’t tell one girl from another in person. I can only tell by looking at a picture. So I wouldn’t send him anyone, that’s his expertise. Once in awhile I suggest that we do a girl we’ve done before again because I like her.

COLACELLO: Are you worried about competition from news magazines like Playgirl or Viva?

BROWN: Not really. I like competition. People don’t buy just one thing. If a woman likes two magazines she’s going to get the money together to buy both. What is bad for the magazine business is when magazines fail. It is simply not good for any of us that Life and Look are no longer here, because people stop developing as writers for magazines. They go into film or TV, they think, Well, the magazine market is dried up. But competition is healthy. Alexander’s stimulates business for Bloomingdale’s and vice versa. It’s unrealistic to think you can only have one good product. People are not that poor. They can buy what they want. Viva will probably be different from us. Their features on men and women will probably be just the bitter end.

COLACELLO: Have you seen Playgirl?

BROWN: Yes, it’s quite interesting. I think the male nude centerfolds are well done. I just imagine Viva and Playgirl will be more daring with their sexy stuff. I mean, you just won’t believe how sexy and they’ll sell like mad. But they’re not going to do the same emotional material that we do, how to learn French in 10 easy lessons, the self-improvement aspect, which we are so heavy into, they won’t have to. But who knows.

COLACELLO: Do you plan more nude centerfolds in the future?

BROWN: We have two more centerfolds ready and I’m looking for a fourth because that was the idea, a series of four. It takes a special type to do it. Someone masculine, relatively young, and I guess exhibitionistic, which is okay. You have to be an exhibitionist to be an entertainer of any sort. You have to be out here having people look at you. I guess anyone with a beautiful body, man or woman, loves to be looked at, but to admit such a thing is a little rough at times. That’s why it’s hard to get people to pose.

COLACELLO: Will you take a more sexy direction with Cosmopolitan in the future?

BROWN: No, no. I am not trying to win any awards or be pretentious or have any terrific message. I’m just trying to make a product that people will buy. A good product.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1973 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.