New Again: Kevin Spacey

Yesterday, Oscar and Tony Award-winning actor Kevin Spacey turned 57. Only two weeks ago, he received his fifth Emmy nomination for his performance as Frank Underwood in Netflix’s House of Cards. It seems that regardless of the character he’s occupying, Spacey is easy to love: He’s played a surprising amount of psychopaths (Underwood, a serial killer, Richard Nixon, Lex Luthor), a maniacal bug (A Bug’s Life), and even a horrible boss (Horrible Bosses). Despite all these hateful roles, Spacey’s undeniable, carefree composure underlines each performance and can charm the pants off of just about any audience member.

In honor of his birthday, Emmy nomination, and continuing charm, we’ve reprinted Spacey’s feature in Interview from February 1997. In it, he discusses his initial foray into acting, his directorial debut Albino Alligator (1997), and his love for when the bad guy scores a win. —Ethan Sapienza

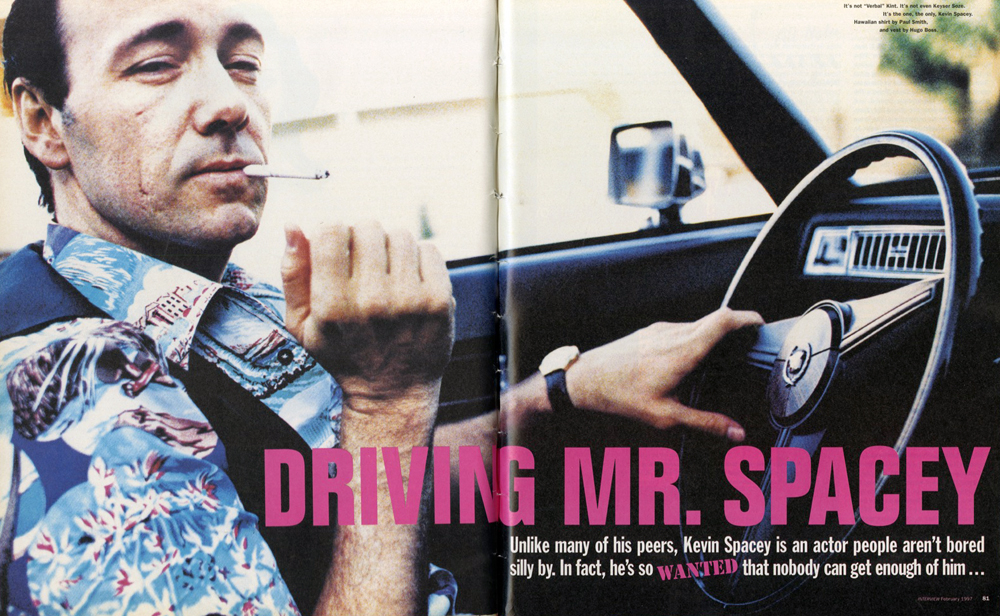

Driving Mr. Spacey

by Mare Winningham

As the question “Who shot J.R.?” was to prime-time TV in 1980, the question “Who is Keyser Söze?” was to hip American movies in 1995. It was, of course, the whining gimp “Verbal” Kint who was revealed as the arch-criminal Söze at the end of Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects. The mystery worked, and Kevin Spacey, the actor who played Kint/Söze, won an Oscar for his performance. The same year, Spacey brought his sardonic calm to the wormy serial killer who presided over a private Armageddon in David Fincher’s Seven, while as Buddy Ackerman in Swimming with Sharks he raised the specter of the Armani-clad Hollywood executive as sadist. In these movies, Spacey demonstrated an uncanny instinct for making even evil ambiguous. He is not an actor who deals in absolutes, nor one who ever tells the whole story. There’s always something else going on.

None of which explains who Kevin Spacey is, or who or what he will be in movies or in life in the future. It’s his talent and taste for the cryptic that makes him a draw, both as an actor and as a personality: “You will never know me,” his entire demeanor says with a smirk, and you wonder who does. His friends? His lovers? His mom? Is his inscrutability calculated, a put on, or just a verbal… kink? Whatever it is, it’s a spirit that informs his directorial debut, Albino Alligator, in which a trio of inept robbers (Matt Dillon, Gary Sinise, William Fichtner) holed up in a bar play psych-out games with its occupants (Faye Dunaway, Skeet Ulrich, Viggo Mortensen, M. Emmett Walsh). This sly, unsentimental drama—or is it a comedy?—opened last month.

Someone we thought might be able to get under the skin of Kevin Spacey is his fellow 1995 Oscar nominee, actress Mare Winningham. Spacey and Winningam have been friends since 1977 when they and Val Kilmer were student actors at Chatsworth High in the San Fernando Valley. As Spacey explains in their conversation, she was one of his key inspirations.

MARE WINNINGHAM: What made you decide to become an actor?

KEVIN SPACEY: I remember the day, because the night before, I’d seen you and Val Kilmer onstage in Chatsworth High’s production of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie at that drama festival [for the best representatives of Southern California high school theater]. I remember thinking, “Those two people are extraordinary, and I wish I could go to their school’s production of All My Sons.” This was the performance when I realized something was happening between me and the audience that I hadn’t recognized before. There was this reaction, and I walked offstage and I saw my friends onstage, frozen, because they didn’t quite know what to do. After the play, a man came backstage and said to me, “My name is Robert Carrelli. I’m the drama teacher at Chatsworth and I would love you to transfer to our school.” And then a bell in my head went, “Ding!” and I thought, “Yes.” That’s how I came to join you at Chatsworth.

WINNINGHAM: What was your very first acting performance?

SPACEY: My parents would say it was when we were living in Santa Monica [Calif.]. They had about six guests for dinner one night, and I walked into the living room quite boldly, put my hands on my hips, and looked at the entire roomful of people and announced, apparently in a very loud voice, “Many one crap!” And I turned around and walked out of the room. My parents still don’t know what I meant. Was I making some kind of social commentary about them having these fake people at their house for dinner, or what? I don’t know.

WINNINGHAM: What was the first award you received?

SPACEY: I won a leadership medal at [Northbridge] military academy, but then they promptly kicked me out.

WINNINGHAM: I can’t believe you really went there. I picture you fucking up all the time and making everyone mad and leading mutinies.

SPACEY: Then explain to me why I got the leadership medal.

WINNINGHAM: Yeah, what was that about?

SPACEY: That right there basically says it all.

WINNINGHAM: What do you think of this scary screen persona that people associate with you now?

SPACEY: Over a spell of about three years, I played a series of roles that were, for me, all very different, but most of them came out within a six-month period. They all dealt with a kind of dark territory that in some cases had been mined before in movies. But it was different from the other kind of work I’ve done over the years—certainly in the theater, where I’ve been mostly attracted to playing men who are in some kind of personal moral crisis, trying to better themselves and essentially be good people within the community.

I was attracted to The Usual Suspects because of its director [Bryan Singer], its writer [Christopher McQuarrie], and because so many things that the movie said to me were beneath the surface. It’s a great thriller or mystery, but on another level it’s a film about the fact that, if you only look at a person through one lens, or only believe what you’re told, you can often miss the truth that is staring you in the face. I think that film is staring you in the face. I think that film also asked me to do the kind of work that was not flamboyant but actually very minimal and very much about how someone’s mind works.

WINNINGHAM: Why did you want to play the serial killer in Seven?

SPACEY: I liked it because it was such a dangerous script and showed just what human beings are capable of. Here was a movie in which Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt, who always win in every movie they ever do, simply don’t win. I felt that was outrageous for a commercial movie. I think what was ultimately scary about it was that people thought that some of the things my character was talking about were right, although they wouldn’t have if I’d sat drooling in the back seat of the [detectives’] car.

It’s been interesting for me to walk down this road. It’s been wild and, in the case of Seven, it was frightening. But I now feel that I’ve gone as far as I can go in exploring that dark side without repeating myself or starting to lose credibility by just showing up and doing what people expect. So I’m not going to look for characters that are emotionally available and not manipulative and not dark, but who will be just as complex and just as interesting for me as an actor, and I hope for audiences as well. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to go off and do really bad romantic comedies.

WINNINGHAM: Where does Albino Alligator, your first film as a director, fit into this?

SPACEY: It’s certainly a dark story, but not so much of the type that I’ve done as an actor. Directing a film was something I was yearning to do. I always wanted to see if I had the capacity to be a good storyteller. With Albino Alligator, I felt I’d found a story that had the potential to be surprising. Then it was just a question of, How do I film this so that people don’t go screaming to the exits after thirty minutes? I also didn’t want it to seem like a film that had my hands all over it. At a certain point in the movie, I want people to forget who directed it and just follow the story and the characters.

WINNINGHAM: Many of the characters in it are ambiguous. We don’t quite know what they’re thinking or what their next movie is going to be. In that respect, they echo some of the characters you’ve played yourself in recent years—especially Keyser Söze in The Usual Suspects.

SPACEY: The Usual Suspects was a good template. Bryan [Singer] and Chris [McQuarrie] believe that audiences are much smarter than most filmmakers ever treat them, and that they are also movie savvy. Essentially, what they did was to use that audience intelligence about film against the audience, to lead them in the wrong direction every time. Similarly, when I found Christian Forte’s Albino Alligator script, I felt there was the same kind of possibility for the characters to take you where you don’t expect to go. I thought that would not only interest audiences, but also actors. We are so often given scripts that, nine times out of ten, are full of trivial, mundane, flat characters that are there just to serve a certain function in the script. I felt that this was the kind of movie in which people aren’t doing that and aren’t what you’d expect them to be.

WINNINGHAM: What quality do you think you have that people want when they go to a movie?

SPACEY: I enjoy watching actors we know a lot about and who always turn in winning performances. But there are other kind of actors who get into films, who don’t look like movie stars, who bring perhaps a different quality you don’t see much of these days. I think I’m probably one of those.

WINNINGHAM: One last question: Where is Keyser Söze now?

SPACEY: [laughs] I would imagine he’s running around pulling a lot of really bad jokes on people. He’s a real practical joker, that guy.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE FEBRUARY 1997 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.