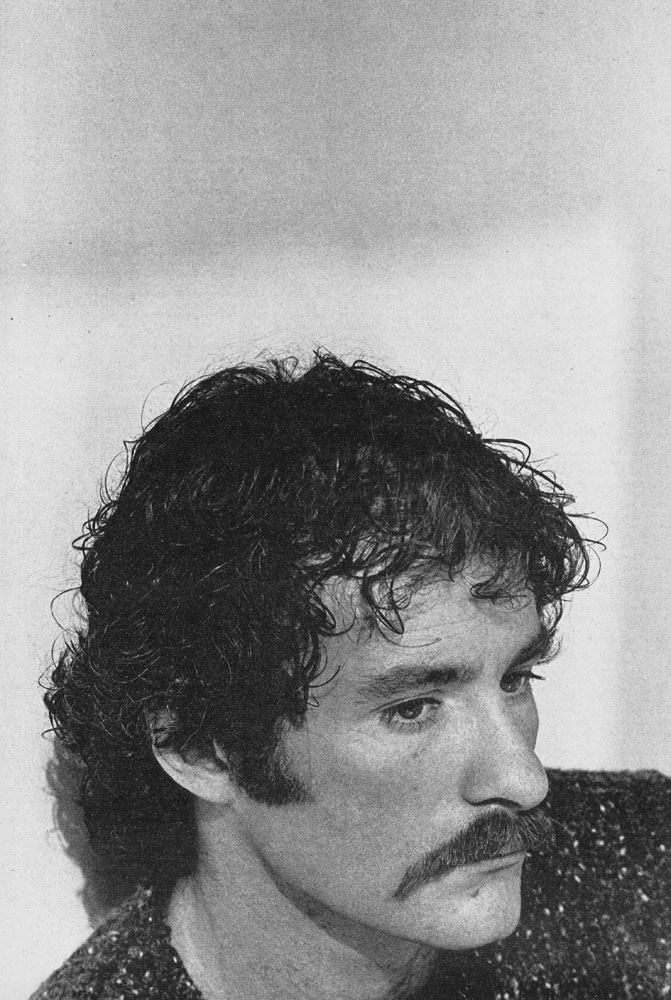

New Again: Kevin Kline

Over the weekend, Kevin Kline took home his third Tony. The award is the Juilliard-trained, Oscar-winning actor’s first since his famed portrayal of the Pirate King in The Pirates of Penzance in 1981, and comes for his rendition of Garry Essendine, the self-obsessed actor at the center of Noël Coward’s comedy Present Laughter.

Today, we look into our archives and revisit our November 1980 interview with Kline, which was conducted just before he received the Tony for Pirates at age 32. In the article, Kline purpotedly laments being compared to Errol Flynn, whom he would go on to play 33 years later in The Last of Robin Hood.

Kevin Kline: The Pirate King of Penzance

By Mark Ginsburg

Being the very model of a major modern pirate is a constant frustration for Kevin Kline. Ironically, he fumes because he reminds people of Errol Flynn each time he plays the Pirate King in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance. For a classically trained, “serious,” as opposed to “commercial” actor, being likened to a matinee idol is blasphemy. Kevin struggles to avoid typecasting both on and off stage, preferring to have no special identity. It is his ambiguous self-image that has given him the freedom to bring enormous life and character to roles from The Lower Depths to The Knack.

His personal life only enhances his swashbuckler image, having been linked with most of his leading ladies, including Roxanne Hart, in Loose Ends; Patti LuPone, a classmate in The Acting Company of Juilliard; and Linda Ronstadt in Pirates. Currently Kevin is on leave from pirate-duty and is the object of the attentions of both Marisa Berenson and Sally Kellerman in Philip Barry’s Holiday, being performed in Los Angeles.

Kevin’s talent as a leading young actor in the American theater has been acknowledged with a Tony Award and a Drama Desk Award for his role in On the Twentieth Century. He received unanimous rave reviews for his sensitive, powerful portrayal of Paul in Michael Weller’s Loose Ends, also on Broadway.

KEVIN KLINE: Perrier with lemon, please. If I lose my voice I’m gonna die. We’re taping Pirates tomorrow night. There’s gonna be cameras all over the place.

MARK GINSBURG: Do those cameras bother you? I mean would you do a television series?

KLINE: Forget it. No. But the more you say no, the more money they offer you. I’m not holding out, I just don’t want to get locked into playing the same character every week for seven years. That’s not what I want to do.

GINSBURG: Have you seen many actor friends get sucked in by a TV contract?

KLINE: Yes. They get lots of money. Most of them talk about how much they miss the stage and want to come back to it.

GINSBURG: How do you see the progression of your career?

KLINE: I see a steady downward slope toward oblivion over the next three years. I’m pessimistic. Everything that’s happened to me so far has been kind of flukey. I went into Twentieth Century because I wanted to work for Hal Prince. The part was too small according to my agent. I had been doing only leading parts, and he thought I should continue that. But the part was enlarged in rehearsal: songs were added, and it became more physicalized and showy. Then I won awards and got attention.

GINSBURG: Did you have any misgivings about playing in Pirates?

KLINE: Many misgivings at first. I didn’t want to do another musical, necessarily. Too many risks. I thought I didn’t have the vocal chops for Gilbert and Sullivan. But it was fun, and I’m glad I did it.

GINSBURG: What kind of role would you have preferred?

KLINE: I had just done a year of Loose Ends and wanted to do Shakespeare or something stylized or period, the classical repertoire. But there isn’t much of that in New York. Because of my classical training there is a conflict at times whether I do something even slightly commercial, or popular. The attitude is that if it’s successful, there must be something wrong with it, like TV—it’s cheap. If it bombs I’ll know it’s good—really warped thinking. But now I feel there are a lot of great things that are also popular, like Beethoven, Mozart, Mornings at Seven, Pirates of Penzance.

GINSBURG: What about work in experimental theater?

KLINE: I did that. I did Viet Rock when I was in college. I’ve played an amoeba. I played half a soul once.

GINSBURG: Where?

KLINE: At Indiana University where I was a music major for two years, majoring in piano, conducting, and composition. Then I took an acting class, tried out for some plays, and started linking that. So I got a B.A. in theater. Then I came to Juilliard and was in the first class of acting division, from which John Houseman formed The Acting Company. They’re out there on the road now somewhere, bringing theater to the hinterlands.

GINSBURG: How does it feel to go from a razzamatazz musical like On the Twentieth Century to a more intimate, straight drama like Loose Ends? Does your support system change?

KLINE: It felt great going down in scale because I knew the audience wasn’t going to go away humming the sets. Loose Ends is an actor’s play; it’s about people and what happens between them. Zack Brown, who designed the set, and Alan Schneider, who directed it, had the good sense to keep it as spare as possible. The people were featured. But when I came to it two days after Century closed my first instinct was to get up and move around a lot and do a physical shtick, which was inappropriate. Weller writes brilliant dialogue, which sounds like the way people talk. But isn’t. It’s poeticized, heightened, and charged. The theatricality I brought with me from the splashy musical informed the work in a good way. I learned theatrical energy and how to control it. Had I not done so, it would simply be like two people sitting at a table talking, just like us, only much more boring.

GINSBURG: In Pirates there was a point in the two times I saw the show, where you and Rex Smith turned to each other and broke out laughing totally out of character. Why did you break the rhythm this way?

KLINE: We cut that out later. It’s just something that happened. The song ends with all this dancing and I was breathing real heavy, and Rex leaned over to me and said, “You got snot coming out of your nose.” And I just cracked up. I started laughing and looked down and he pulled my hair up. Then he tried to crack me up at another point, too. I don’t like it. It can look like it’s the actors finding themselves so amusing that they’re cracking up. Red Skelton did it on his show all the time. You get a laugh and the audience seems to love it. What was your reaction to it?

GINSBURG: I didn’t like it. When it happened a second time I thought it was a planned bit to milk an extra laugh.

KLINE: It happened and a lot of people said to keep it in.

GINSBURG: But the audience loved it.

KLINE: Well, the audience is crazy about a lot of shit. But the show is so open and tongue-in-cheek.

GINSBURG: How was working with Linda Ronstadt and Rex Smith, who are rock ‘n’ rollers, not trained actors?

KLINE: We didn’t have the same vocabulary, or approach. I had to explain to Linda that she was upstaging herself. That if she was turning upstage to say that line, the audience couldn’t see her. So she said, “But I always sing upstage to my band.” When you are learning how to open up to an audience, there are certain rules. Like you don’t move on someone else’s lines, and how to gesture with your upstage hand. Linda would go, “They went that way,” while she was singing and block her face completely. So I showed her how to do it differently.

GINSBURG: Of course, the funny thing is that it really didn’t matter in this case because she was so miked that we could always hear her in spite of it.

KLINE: By the same token Linda and Rex taught us some things.

GINSBURG: Like what?

KLINE: Well, that thing where Rex and I lock heads on “cat-like tread.” That wouldn’t have happened working with another actor. It was kind of a Mick Jagger and Keith Richards kind of thing. It’s a getting down, rock ‘n’ roll thing. Rex and I jam a lot, we’re working on a song together. I would just start playing, and he would be riffing, making up words, and getting me to simplify and clarify. He’d make up the words instantly, suddenly it would sound like a rock ‘n’ roll songs.

GINSBURG: What do you do during the months of unemployment?

KLINE: I had three months between Loose Ends and Pirates, and called it a vacation. I went to an island in the French West Indies, which I won’t name because I don’t want it to get spoiled.

GINSBURG: Did winning a Tony affect your career?

KLINE: I got approached by a lot more agents, and wondered where they were before. More scripts came in. Suddenly I didn’t have to audition, which seemed a bit silly. But it wasn’t because I had won the award, it was because the agents had seen enough of my work so they felt they could trust me. They offered me Loose Ends, and I asked to read for the part to make sure that I was what they wanted. I was insecure.

GINSBURG: If acting hadn’t worked out for you, where would you be now?

KLINE: Playing piano somewhere. Some new music that hasn’t been discovered yet. Maybe if things weren’t too bad I’d be in a cocktail lounge playing cocktail music.

GINSBURG: Where?

KLINE: Muncie, Indiana. As nowhere as you could get. After graduating from university, I went to an audition for regional theaters. I didn’t even get called back and was bummed. I thought I was no good. The Juilliard audition was a week later. I thought of skipping it. It doesn’t take much to deflate entirely my sense of self-worth. If one person I respect says, “you suck,” I’d worry about it.

GINSBURG: Could this person be anybody, like a critic or another actor?

KLINE: Not a critic. But an actor or director.

GINSBURG: What actors in particular would you like to work with?

KLINE: Duvall. He’s the best. I’d even do a commercial or a soap with him. I’d be scared shitless working with him, but I might also be inspired by him. And if I could just meet Olivier, I’d be happy.

GINSBURG: How are the scripts you’ve been getting?

KLINE: Very few are any good. And the ones that are, are not what I want to do. I like variety, which is frustrating. But I’ve always been picky. I was afraid Pirates would be too much like Twentieth Century, broad comedy. But my agent talked me into it. I was spoiled by the range of a repertory theater.

GINSBURG: Did you change the spelling of Kline from Klein?

KLINE: No. My father, who is from Cincinnati, is from German-Jewish extraction. My mother, from St. Louis, has an Irish-Catholic background. I was raised Catholic. But my father is Jewish.

GINSBURG: But you spell Kline the Irish way.

KLINE: My father said his father and grandfather spelled it that way.

GINSBURG: What was the extent of your pirate research for Penzance?

KLINE: I read a book about pirates. I reread some Treasure Island, popular at the time when the show was written.

GINSBURG: Does playing a glorified villain bother you?

KLINE: You know how we say, “That’s really bad,” and mean it’s really good? That’s the Pirate King. He’s baaad. He wants to be bad, but he’s really a mush-heart. He’s honorable, a nobleman gone wrong, gone rough.

GINSBURG: Do you believe in the occult?

KLINE: Yes. I think there is something else out there that we don’t know about. I went to an astrologer once and got all this stuff about past lives. But that’s the extent of it.

GINSBURG: Do you believe in theatrical superstitions?

KLINE: Yes. I room with Rex and Tony Azito. We share a dressing room. Rex whistles constantly. Each time he does, I send him out, make him turn around three times and spit over his left shoulder. Never whistle in a dressing room. Never say, “Macbeth,” in a dressing room, refer to it as the Scottish play. Never even joke quote Macbeth. With Rex, it was a running joke. Finally, we worked it out so that right before a show he would do it to makeup for the times he whistled. It’s stupid but it’s fun. It’s ritual. Rex caught on to it. It’s not just doing a show, it’s going onto a stage, a special event.

GINSBURG: Any actresses in particular that you want to work with?

KLINE: Dangerous question. I could get in trouble with an answer. I have friends who are actresses and I have a great rapport with and would like to work with again. Then there are others…

GINSBURG: Are you more likely to have a relationship with an actress or non-actress?

KLINE: Well, the people in my immediate milieu are actresses, so that’s who I see.

GINSBURG: Do you see yourself having a family?

KLINE: I actually do, someday. And I may have one somewhere that I don’t even know about. I would like children, and a mate. Maybe even a wife. Sometimes between jobs I’ll work on that. Right now I’m worried about finding a place in L.A. to stay, and rehearsing. I’m starting to see a pattern that would enable me to have a family even though I move around in my profession. I’ll probably acting for the rest of my life.

GINSBURG: Are all the people in your Juilliard graduating class still acting?

KLINE: One woman I ran into on the street was writing a book and running a bookstore. But I think the rest are all still involved in acting.

GINSBURG: Did Patti LuPone’s success surprise you?

KLINE: Not at all. She was in my class and we did a lot of plays together. From the first time I saw her it was pretty obvious she would do well.

GINSBURG: How old are you?

KLINE: Thirty-two.

GINSBURG: Were you where you wanted to be by the time you were 30?

KLINE: Yes. I’m right about there. I’m doing what I want to do. I just want to keep it up.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE NOVEMBER 1980 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.