New Again: Emilio de Antonio

Last Friday, the new Whitney Museum of American Art opened its doors to the public at its new location in the Meatpacking District. Its inaugural exhibit, “America Is Hard To See,” includes more than 600 works from the Whitney’s own collection from the beginning of the 20th century to the present. Organized chronologically, the exhibition explores the experiences of artists as they responded to the constraints and liberties of working within American culture. In accordance with the political and social commentary of many of the works, the exhibition borrows its title from a poem by Robert Frost and a political documentary by Emile de Antonio. In honor of the opening, we’re reprinting an interview with de Antonio from our July 1984 issue. The conversation reveals his stance during some of the most controversial and poignant moments in American history—from Nixon’s presidency to the dodgy activities of the FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover. —Savannah O’Leary

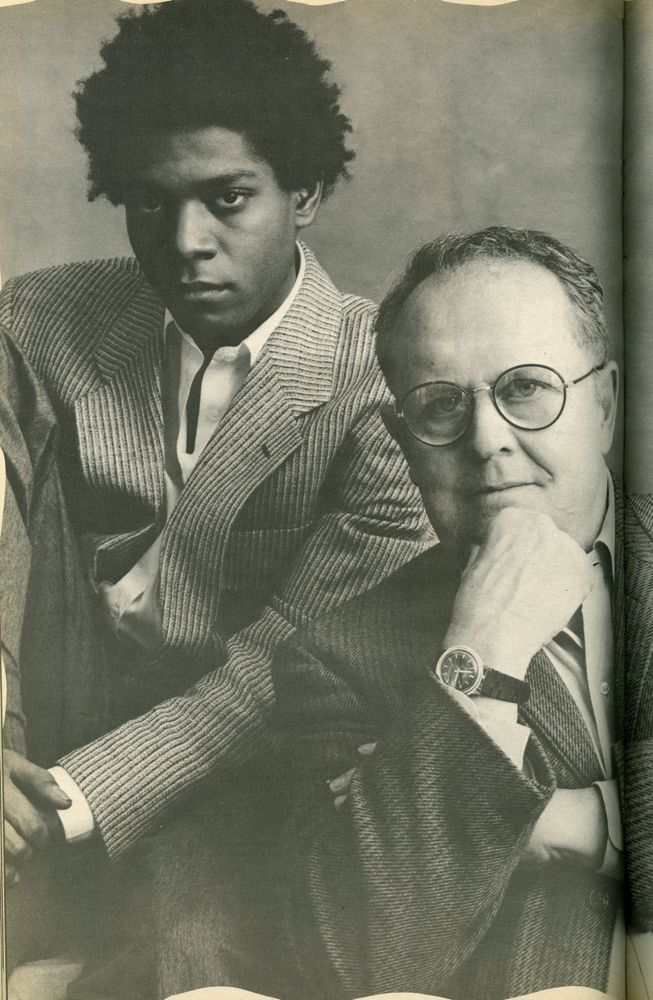

Emile de Antonio with Jean-Michel Basquiat

Elaine calls him the greatest documentarist in the world, and the greatest drinker. Emile de Antonio—anarchist, ex-professor, author, and the only filmmaker on Richard Nixon’s enemies list—has spent the last 20 years making trouble for the big boys with movies like Point of Order (about Sen. Joseph McCarthy), In the Year of the Pig, Millhouse: A White Comedy, In the King of Prussia and Painters Painting. This recent work, consisting of conversations with friends like Rauschenberg, Johns, Stella, de Kooning, Castelli, and Frankenthaler, is the subject of a new book published by Abbeville Press, subtitled “A Candid History of the Modern Art Scene, 1940 – 1970.”

Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the son of a prominent doctor, “D” went to Harvard at 16, taught Philosophy for a short time at William and Mary, made a lot of money in business and moved to Long Island, where neighbor John Cage introduced him to “Bob and Jap” (Rauschenberg and Johns), both still struggling and unknown. Gifted with an eye for genius, D helped the painters—and many others to come—in finding dealers and buyers. He filmed curator Henry Geldzahler’s landmark show of 43 modern artists at the Metropolitan Museum in 1969, and has continued giving painters—whose company he values over that of writers or other filmmakers—the majority of his social and professional attention.

De Antonio lives with his sixth wife, a psychoanalyst, in an East Village townhouse, where two major projects are currently underway: a book on art empire-builder Leo Castelli, and an autobiographical labor entitled A Middle-Aged Radical As Seen Through the Eyes of His Government, about his life and lawsuits against the FBI Taken from that organization’s 5,000-page dossier on de Antonio, the film will star Martin Sheen as the reeling rebel with the last word.

EMILE DE ANTONIO: My new book is called Painters Painting. It’s based on a film I shot in 1970, then interrupted and finished in 1973. Henry Geldzahler did a show for the Metropolitan Museum centennial (which my book documents), and this was probably the only time in the history of this country or of any country that you’re going to have a collection of major modern painting like that at one time. Modern [art] doesn’t travel the way, say, Rembrandts do. Modern is more fragile basically, like the painting of yours I just saw that’s on pieces of wood. Some of those early Rauschenbergs are, and an early Jasper Johns was made with a bed-sheet—his first American flag—the sheet he slept on. Anyway, it was an enormous show, and it filled huge numbers of galleries. I had to sign a lot of papers to get into the museum at night. I had to hire four Metropolitan Museum guards—ex-cops, so they would watch my crew and me to make sure that we didn’t steal anything. It’s very hard to steal a painting anyways when you’re there in the middle of the night. I bought them beer and sandwiches, and after three weeks they were pretty nice.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: You’re a very political person. Tell me about your film Millhouse.

DE ANTONIO: After I shot the material for Painters Painting, the phone rang one day and some guy said, “Listen, we just ripped off the XYZ network, and we have all the Nixon material that ever existed, everything—Checkers, all this stuff that nobody was allowed to have.” I said, “Why are you telling me this?” He said, “Well, we know your work; we’d like you to make a film out of it.” I said, “I can’t make a film out of it, I’m working on a film, and what do you want out of all this?” He said, “I don’t want a penny, I just want you to make a film.” These were passionate times in 1970. There was Vietnam, Nixon was in office, there was no way to ever get him out. I asked the guy for 20 minutes, and I thought, if I do it, I’ve got to put all this painting stuff aside, but I do want to do it because I am a political person. I hate Nixon, I hate the war and I hate everything those people stand for. So when the guy called back I agreed. I said, “I’ll give the super 20 bucks and you come here around midnight; there will be nobody in my place. The super will let you in, you put it all there and get out.” I said, “You don’t want to know me?” and he said, “No.” The next morning I walk in and there were 500 cans of film. There was enough film there to make 50 movies, probably. I went through it all. There was stuff about the Native American takeover of Alcatraz, there was a lot of civil rights stuff. I took all that and gave it to the Cubans.

BASQUIAT: The Cubans?

DE ANTONIO: Castro’s people. I gave it to those guys so they could make a film out of it themselves, and I kept all the Nixon material.

BASQUIAT: What did you give to Castro?

DE ANTONIO: Native Americans taking over Alcatraz, that had nothing to do with Nixon.

BASQUIAT: I don’t understand. Why the Cubans?

DE ANTONIO: Because I’m sympathetic to Castro. We put three industries into Cuba: sugar, whores, and gambling. I’m not against the United States or the people of the United States, but I’m against interfering in Central America. I’m against our going into El Salvador and Nicaragua. We went into Grenada, among other things, because we lost the war in Vietnam. We finally found some small place where we could send in the 82nd Airborne, Rangers, Marines…I mean, it’s insane. But I was in World War II. That seemed like it was worth doing. See, the thing that bugs me about Reagan is that he’s also destroying our language; there’s no meaning. He went on television and said we did not “invade” Grenada—that was a word the press used, “invasion.” It was an invasion. We didn’t go there to make love, we didn’t go there to dance, we went there with arms ready to kill people who would pick up a gun on turf that wasn’t ours. This is the most inhumane government I’ve ever seen in the United States.

BASQUIAT: Is it scary to you?

DE ANTONIO: Sure.

BASQUIAT: You seem to be a very important—

DE ANTONIO: Agitator.

BASQUIAT: No, journalist.

DE ANTONIO: I’m not a journalist; I’m an artist. I make films that aren’t like all the trash.

BASQUIAT: No, you seem like a very real journalist. Your business seems to be compiling information.

DE ANTONIO: Most journalists deal with fiction, but I deal with the documents…Millhouse became a very successful film. It played all over the world. I’m the only person who put in a film what the black riots in Miami were about in 1968, when Nixon ran. That to me was just as important as Nixon getting nominated. People were killed there and the riot was by the police against the people. One of the things I did, for instance…Nixon almost begins to say in the 1968 convention acceptance speech, “When I was a boy I had a dream…”

BASQUIAT: He said, “I have a dream”?

DE ANTONIO: Not precisely those words. It had those resonances. It sounded like that. He said, “I see a boy and he hears the train go by at night,” and it was exactly with the cadences of King. I love making people realize what the world is really about…People used to say to me,” “D, how come you have all these left-wing politics and you like this decadent painting?” Most radicals don’t like modern art, they don’t like modern painting, modern writing.

BASQUIAT: Why?

DE ANTONIO: Because so many radicals are conventional in everything but a single hard political line. And that’s as boring as being like Nixon or Reagan.

BASQUIAT: So your book, Painters Painting, is based directly on the film?

DE ANTONIO: What I find interesting about the book is the same thing that’s interesting about the film.

BASQUIAT: Why make a book today out of a film you shot in 1970?

DE ANTONIO: I thought the period of New York painting covered by the film was just as important as the Renaissance, or Paris in the second half of the 19th century. No written record of those times exists…

BASQUIAT: But Leonardo kept a lot of his own records.

DE ANTONIO: Those are his own records, but it’s not somebody pushing him and leading him into a conversation. I wanted a written record of de Kooning, Pollock, Stella, Rauschenberg and Johns and many others. I knew all those people, it was off the cuff, it was immediate. It’s what they really thought about how and why they worked. There had been only words about them.

BASQUIAT: In this movie did you interview all the artists?

DE ANTONIO: Yes, on film.

BASQUIAT: Who was in the show at the Metropolitan?

DE ANTONIO: De Kooning, Pollock, Kline…

BASQUIAT: Pollock was still alive?

DE ANTONIO: No. There were dead people in it, like David Smith and Pollock. But Stella, Rauschenberg, Johns, Lichtenstein, Ellsworth Kelly, some of the minimalist sculptors were there, Barnett Newman, who was a friend of mine, and Rothko. Rauschenberg has a building on Lafayette Street. I filmed him over there. Part of that building is a four-story chapel, and I put him on a ladder higher than this room, at the top of the skylight and filmed up. He had a Japanese houseboy. Sixteen millimeter film takes 10 minutes a roll. So at the end of each roll the houseboy would hand him another big glass of Jack Daniel’s. He was so good in the beginning, but the end of it I couldn’t use…I loved their work. Their work is why I made the film. I liked being in the spaces where they painted and have them talk about what they did, how they did it, why they did it, when they did it. It’s funny that a camera crew sees people differently. They’re not like news crews or television crews who are bored as hell—they do the same thing every day. These are freelance people and most of them want to become directors themselves…I was the only film director on Nixon’s enemies list. When you think that the government had nothing else to do than look at movies I made against the President…There were all these memoranda, “To John Dean From Haldeman—subject: Emile de Antonio, Millhouse film; let us devise means to release derogatory FBI files of de Antonio to friendly news media.”

BASQUIAT: Fake ones?

DE ANTONIO: No, the FBI. has many pages on me. I talk against the FBI at the drop of a hat. I thought it would be good to do a musical called Johnnie and Clyde, about Clyde Tolson and John Edgar Hoover. Somebody ought to do one about these two middle-aged guys who were persecuting anybody who was having any fun in life whether he was heterosexual or homosexual.

BASQUIAT: Talk more about J. Edgar Hoover. I think he’s interesting.

DE ANTONIO: J. Edgar Hoover was born January 1, 1895. His father was a bureaucrat in Washington. His grandfather was a bureaucrat. He became head of FBI in 1924, and he was still the head of it in 1972 when he died. He was in the saddle 48 years. Nowhere, not in Russia, not in Nazi Germany, not in the history of the world has one guy run the secret police for 48 years…The minute he died everybody in the FBI was ready to pounce on his files, because his files were all about John F. Kennedy and who he was sleeping with, it was about what Nixon really did, it was about what LBJ really did…

BASQUIAT: That would make the great American novel.

DE ANTONIO: That’s the truth; he had it on everybody. His files, one at a time, would expose everybody in political life. He wouldn’t care about de Kooning or Pollock and he wouldn’t care about baseball players unless they said something. If Babe Ruth got up and said the FBI was full of crooks then they would have had a file on him, too…I don’t know what J. Edgar Hoover knew about painters; I’m sure he knew nothing about painting…Picasso was a Communist, that he knew. Picasso was a member of the communist party of France. He did the peace dove. The hardline communists hated his paintings. They thought he did decadent, bourgeois painting. What those people have to say is economically not incorrect; it’s artistically incorrect. They say art should belong to the people, whatever that means.

BASQUIAT: It does, though.

DE ANTONIO: It doesn’t. The fact that you make it at 22 is extraordinary, but most people 22 have never really seen a good painting, a real painting, and particularly not black kids. They don’t understand Picasso in relationship to your work or for that matter Barnett Newman’s work. They don’t even know the Picasso. You know, school is a drag, but you drag your ass through.

BASQUIAT: I never learned anything about art in school.

DE ANTONIO: No, that’s what I’m saying. When Frank Stella went to school he knew that he wanted to be a painter when he was about 14.

BASQUIAT: I knew I wanted to be a painter the whole time. I wanted to be a cartoonist, though, when I was 11 or 12 or 13.

DE ANTONIO: Stella went to a very fancy expensive school.

BASQUIAT: Which one?

DE ANTONIO: Andover, before he went to Princeton. They had a teacher there who taught art and had his own collection. He and his wife would take the better students down to New York to the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan. They’d say, there’s the painting, this is what this is. They didn’t explain it away—they just revealed the presence of the stuff. It had a very big influence. Frank wanted to be a painter and it got him going.

BASQUIAT: I wrote to J. Edgar Hoover as a kid, did you know that?

DE ANTONIO: No.

BASQUIAT: I sent him a drawing.

DE ANTONIO: That’s wonderful, and you got a letter?

BASQUIAT: I didn’t get any letter back. It was one of the first art things I did. I must have been eight or nine.

DE ANTONIO: He answered practically everything unless he thought it was insulting.

BASQUIAT: I got no letter back. It was a design for a gun.

DE ANTONIO: That he might not have answered.

BASQUIAT: It was by a child, though. The bullets were really, really big…I know you don’t go to other filmmaker’s movies. Don’t you think your attitude is pretentious?

DE ANTONIO: No. I see films of the past, I see works I regard as significant, but most mass-produced films are just like Fords. They’re not art, they’re not politics, they’re just something to be consumed.

BASQUIAT: Are you interested in the new painters?

DE ANTONIO: I stopped being interested because I saw nothing new until I saw your work and Andrew Lyght’s. Now I think I’m going to look around some more.

BASQUIAT: All those names you mentioned before, the painters in your book and film, what do you think of their work today?

DE ANTONIO: Well, I think inventive people remain inventive. New ideas come out. I don’t think we’re surprised that Picasso painted interestingly all those years. The trick is to survive physically.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JULY 1984 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.