Lord Whimsy

A lot of the most interesting reading today is produced spontaneously by civilians and available gratis on the Internet. A favorite blogue (my variant spelling) is The Affected Provincial’s Almanack (a Journal of Aesthetic Ecologies, Microluxury, and Other Pretentious Twaddle). In this jaded world, surprise is perhaps the last true luxury, and the author of this digital diary, Lord Whimsy, is a very reliable purveyor of the entirely unexpected. He also authored a very amusing book of disguised or tarted-up philosophy, The Affected Provincial’s Companion, Volume One (Bloomsbury), which, it seems, may be made into a movie by Mr. Johnny Depp.

GLENN O’BRIEN: Where do you come from?

LORD WHIMSY: I was born in eastern Kentucky of the customary stock-Scots-Irish,

Choctaw, Cherokee. But I grew up in a small, working-class bay town in southern New Jersey. As a boy, I was a feral sissy, equal parts Huck Finn and Little Lord Fauntleroy. I was a voracious collector of butterflies and seashells. I would go bird-watching with a beat-up old pair of opera glasses-binoculars were expensive. I became completely obsessed with heraldry for a couple years, if I recall. There were plenty of other things to keep me occupied: dense woods, marshes, beaches, crabbing, derelict concrete ships, violent townies, bait shops, doo-wop motels and diners, snapping turtles, boardwalks, fishing, Victorian houses, tidal pools, nudist camps, elephant-shaped buildings, colonial folklore, nautical kitsch, and casino chintz. Sadly, this place no longer exists.

GO: How did you happen to elevate yourself to lord status?

LW: Well, I originally wore the cardboard crown in jest, but people insisted that I keep the thing on. I’ve grown into my sobriquet over the years. Walking down the street once felt like a performance, but now it feels like a recital. Today, what you see is what you get: a failed dandy, a passionate dabbler, and a middle-aged weirdo. America has had its share of tin grandees-Emperor Norton 1, Lord Buckley, Duke Ellington, the King, Sun Ra, Lord Dexter, et cetera. Of course, it’s shamelessly ludicrous and grandiose, but I believe in the open, generous kind of narcissism that invites others to play, not the churlish, disingenuous kind of narcissism that takes itself too seriously to court foolishness. My fake lordship has gradually become as much about service as it is about smart-assery. I give readings. I serve on committees. I sign and return copies of my book to readers by mail. I provide essays to magazines. I answer people’s questions about clothes and plants via e-mail. I conduct wildlife tours. I’ve penned liner notes for albums. I’ve given guest lectures at universities. I’ve delivered keynote addresses. I’ve designed signature pocket squares. I’ve donated personal effects for charity auctions. I’ve even conducted a few weddings . . . What began as a lark has become a public obligation-an office, of sorts. Some people become clergy, firemen, doctors, or professors. I’m a whimsy.

GO: Did your book, The Affected Provincial’s Companion, Volume One, result from a compilation of pieces written for other purposes?

LW: It started as an exercise inspired by the wonderful charts I would find in 18th-century pamphleteering screeds and 19th-century faux-scientific treatises. My essays grew from the captions that accompanied the charts I made. I wanted to employ an entertaining style of writing that was unapologetically pompous and florid but crisply edited. After whipping up a few of these chart squibs, I shared them with friends over drinks. The beer arcing out of their nostrils encouraged me to keep tinkering. I soon found myself writing and editing for The Philadelphia Independent, a smart little newspaper started by a group of bright young pennies. My own prissy twist to Poor Richard’s Almanack was an ideal fit with the overall theme of the paper, and I began to gather a small following. Young men started to wear ascots and roll their Rs in public. After the Independent decided to close up shop, I gathered my tables and tirades into a slim volume, which I designed and illustrated myself. I offered it for sale on my website. When I started receiving orders from Sweden and France, I thought I might send something to a literary agent. I sent a sample to one agent, Peter Steinberg. Two days later, Peter called me, and about a week later, I had multiple book-deal offers. A little while after that, Mr. Depp’s production company, Infinitum Nihil, entered the picture, and we soon had directors, screenwriters, and other riffraff visiting our house.

GO: How would you describe that book?

LW: I designed, illustrated, and typeset the entire book myself. The leaf-green hardcover is stamped with a silver-foil botanical design, with bright magenta endpapers inside, suggesting the maw of a Venus flytrap. The paper I selected is warm eggshell. It’s a collection of essays, anecdotes, ribald poetry, and satirical diagrams. It draws from the life I led for 12 years in rickety, plant-filled Army barracks in the Pine Barrens of rural southern New Jersey.

GO: What is the history of your blogue, The Affected Provincial’s Almanack?

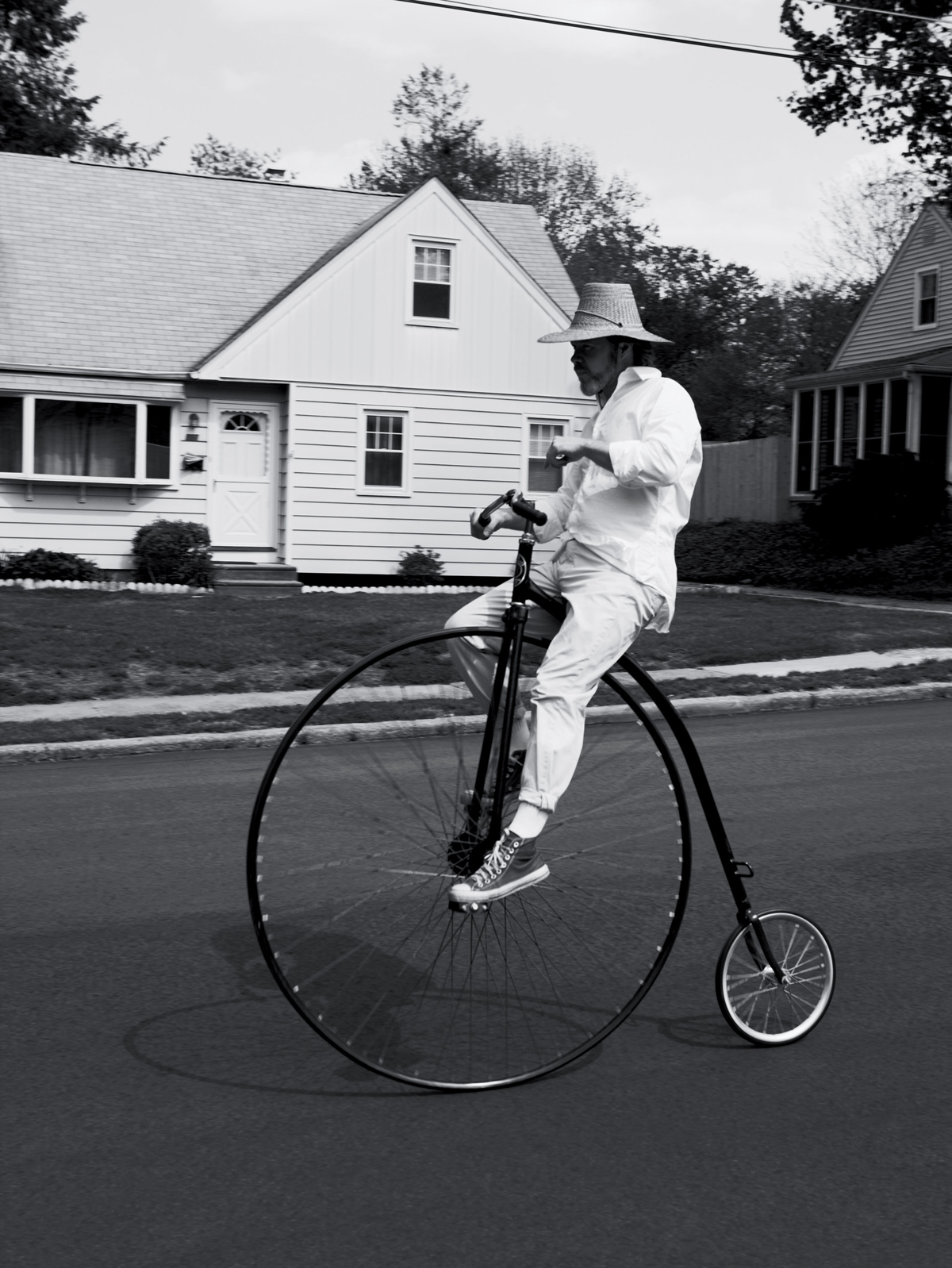

LW: The Almanack is an online collection of dispatches from my daily life. One day it might be pictures of an odd, rare plant that just bloomed in my garden, or photos of my visit to an old orchid nursery greenhouse that’s been colonized by tropical tree frogs. The next day I might post about my friend Adam Wallacavage’s handmade octopus chandeliers. It may seem a mixed bag, but the posts tend to be about anything that represents the qualities I enjoy: improvised, humane, modest, open, quiet, light, poised, generous, delicate, introspective, humorous, elegant, and organic. I generally occupy myself with what might be called aesthetic ecologies-art that acts like nature, and nature that acts like art. Some people have called it a men’s fashion website, but I’m not really interested in fashion. I prefer style, which to me is more accessible, individual, and idiosyncratic. You might see street style on my journal, but rarely haute couture-someone making a $40 hat look like it cost $400 is always going to be more interesting to me than someone simply buying a $400 hat. As Logan Pearsall Smith said, “You can’t be both fashionable and first-rate.”

GO: You draw interesting distinctions between dandyism and foppery. Are you a dandy and not a fop?

LW: Well, I’ve always had a sartorial itch. Life is a brief thing—an occasion—so one may as well dress for it. Both the fop and the dandy are very rare breeds. Although both treat their shoes as an ambulatory stage, there are differences between them. Dandies cultivate a perverse subtlety and restraint, but the fop favors exuberance, ornament, and overstatement. A dandy is not necessarily a gentleman—in fact, he is often a sly parody of one. A gentleman is cultured to the point of refinement, but a dandy is cultured to the point of decadence. Dandyism is a paradox: It’s both reactionary and revolutionary; outrageous and conformist; working within convention but pushing at its margins, giving it a slight twist that may not at first be noticeable. Each dandy must reinvent dandyism in his own image, making it fresh, vital, interesting. It takes courage to be a fop today. Fops do more with their eyeliner than most men can with a full sack. They’re orchidaceous creatures, simultaneously angelic and grotesque. Unfortunately, even people in so-called progressive, artistic circles seem fairly intolerant of such overt artifice. I’ve noticed that the word camp is being used more as a pejorative term now, which is a little sad, since that very sort of exuberance and theatricality has given us so much in the past: pop, glam, punk, et cetera. I worry that there will never again be Liberaces, Screamin’ Jay Hawkinses, or Lux Interiors walking off planes in capes-Sebastian Horsley can attest to this. God save us all from the timid deference to convention that masquerades as good taste! Personally, I’ll take refined vulgarity over vulgar refinement.

GO: Your blogue is increasingly concerned with your activities as a naturalist. Explain your choice of a semirural lifestyle.

LW: I originally studied to become a biologist, and I often employ my incomplete knowledge of biology as an illustrator. If you go to the American Museum of Natural History, you’ll see more than 300 species-identification illustrations my wife and I made for the permanent displays in the refurbished Milstein Hall of Ocean Life. I spend as much time as possible in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, scouting for rare plants and animals. It has a subtle beauty, the Pine Barrens. If you get up close, it will take your breath away. You can find plants in the Pine Barrens that live nowhere else on the planet, and the habitats vary widely. Some microhabitats can be as narrow as 4 inches, beyond which life for the plants in question is impossible. I sometimes find vulnerable, botanically significant areas, and I notify local conservation groups or land trusts in the hope that they might be able to purchase the property. A good portion of the Pine Barrens is federally protected, but not all of the sensitive areas are. I’m doing a lot of volunteer work right now for Bartram’s Garden, the oldest botanical garden in the United States. It was once a Quaker farm and the home of naturalist-explorer William Bartram, but it is now an oasis of green, deep in the industrial landscape of West Philadelphia. The contrast with its surroundings is jarring but fascinating. Wild plants not seen there in decades are now beginning to return, which is an encouraging sign. I help with landscaping, sit on a couple of their committees, and serve as a wildlife guide on their field trips, for which I get paid in plants. The rest of the time, I can be found in my garden, up to my chest in a creek, or with a ladder, helping my neighbor trim the branches from the old trees hanging over the water by his house. We then listen to tree frogs over gin and tonics and watch the fireflies. To me, this is luxury—after all, what could be more luxurious than enjoying and cultivating things that took millions of years to make? To me, luxury is less about cost, pedigree, or provenance than the sensed qualities of a thing. I’m a microvoluptuary—an aesthete, not a connoisseur.

GO: What are your hobbies?

LW: I don’t believe in hobbies. Hobbies are passions exiled from daily life, set aside to be indulged out of view during one’s few precious fugitive hours, as if they were cause for shame. I’m especially fortunate to have organized my life around my interests. My idea of a fun Saturday night is sitting at my desk in my house robe, affixing red felt to the bottom of my coral samples.

GO: What affects you?

LW: Of course there are far too many influences to name, and it’s dangerous to reveal too much of one’s personal pantheon, so I’ll just pick one thing: Philly soul. It was a big influence when I was young, and I still frequent shops in Philly that offer lavender-colored alligator shoes and Technicolor hats; the older gentlemen who still don them are nothing less than heroes. People have forgotten the value of being groovy. You can’t be civilized unless you’re groovy, too.

GO: Please dispel any confusion regarding the other noted Wimsey, spelled differently.

LW: Lord Peter Wimsey of the Dorothy L. Sayers mystery books is a well-known and much-loved fictional character. Lord Breaulove Swells Whimsy obsesses over the scuffs on his shoes and enjoys an occasional pastis.