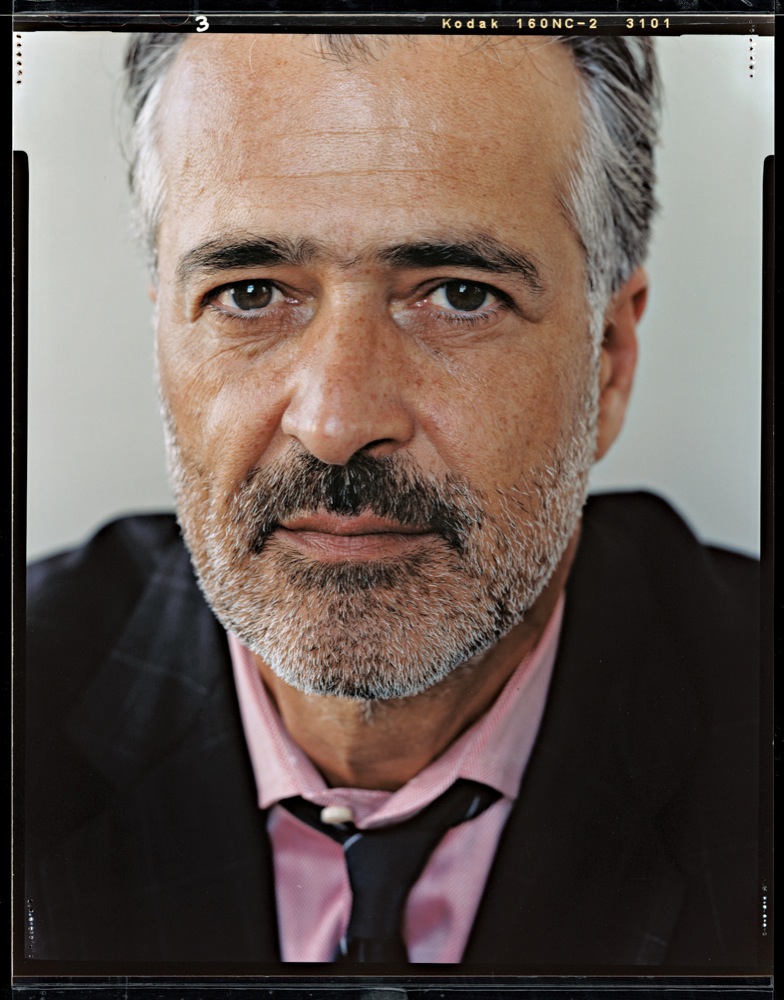

Hooman Majd

When I met Hooman Majd, he had just finished a 12-year run (1986-1998) at Island Records and was the newly installed head of Palm Pictures, Chris Blackwell’s film venture. I was about to start preproduction on my film Black and White (1999), and it took no more than a long lunch to know that I was about to embark on the best experience of my career with a movie executive. As the son of an Iranian diplomat under the shah, Majd, now 51, had grown up as a cosmopolitan citoyen du monde, living mainly in the United States and England but traveling wherever his father’s job took him, including northern Africa and India. The cultural diversity of his background (in addition to a life as a Muslim exposed mainly to Christians and Jews) produced a remarkably shrewd, curious, and tactful mind and an openness to abrupt changes in strategy (on my part) that made directing a film about hip-hop and white fascination with blackness far more pleasant and less volatile than it would have been in more conventional studio hands. His contacts-and relatives-in Iran cut across all political boundaries, and he has served as a translator and guide to current president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in each of his American visits. Majd’s new book, The Ayatollah Begs to Differ (Doubleday), is in equal measure memoir, history, and political analysis. It is written-elegantly-from a perspective whose breadth virtually no other observer of Iran could hope to match.

JAMES TOBACK: Your book, The Ayatollah Begs to Differ, combines personal memoir and sentiment with a rigorous contemporary political analysis. Had you always conceived the book in this way?

HOOMAN MAJD: Yes, absolutely. There are so many books on Iran, whether they’re memoirs about the early days of the revolution [of 1978-79, in which the shah of Iran was displaced by the Islamic republic led by Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini], which are not that relevant to today’s world, or policy books written by academics or journalists in a very dry style. I wanted this book to be something that people could read almost like they were reading a novel, but also to get all the information that they might be interested in knowing about a country that is obviously very much in the news today-and also very dear to my heart because of my own background.

JT: I sense a division of mind and heart in the book, which is to say that you clearly write as an American, but also very much as an Iranian. How do you think of yourself in a nationalistic sense?

HM: Well, that’s a question that has come up throughout my life. I was born in Iran, left at a very young age-less than a year old-and grew up and was educated in the West. I grew up thinking of myself as an American but also, because of my parents and the Iranian culture that was in our home, as an Iranian. So if there’s any such thing as dual loyalty, then I have it-at least culturally.

JT: Given that sense of division, how do you feel about the tense state of American-Iranian relations right now?

HM: It’s incredibly frustrating. It’s probably more frustrating to me as an Iranian living in America than it is when I’m over there. Inside Iran, people are actually quite well educated about America. There are things they don’t understand, particularly in the government, but the people, by and large, know the American sensibility quite well, and the reverse is not true. There’s a lack of knowledge about Iran and the Iranian people. Part of the reason I wrote the book is this lack of understanding.

The idea that you can do things in Iran as long as you don’t talk about them is very much a part of the culture.Hooman Majd

JT: Your father was an Iranian ambassador when the shah was in power. Now, of course, the entire Iranian power structure is an obliteration of everything that the shah stood for, but you still have very definite ties to Iran. From what you tell me, that’s not uncommon . . .

HM: Not at all. Before the CIA-engineered coup of 1953 [to depose the elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq and his cabinet], a lot of people from my father’s generation were against the shah. Afterward, there was this kind of realization for the Iranian people that, “Well, America’s never going to allow us to have a democracy, we’re always going to be stuck with this shah, and we’re going to be a puppet of the United States—so that’s life. We’ll get on with it.” It wasn’t so much that they were supporters of the shah—as evidenced by the revolution, the shah had very few star supporters. What happened was the people in control now—the revolutionaries—had a list of enemies who they felt were dangerous and who could potentially start another coup. But they really didn’t care about people like me. In some ways they’re actually fascinated. I have had many Iranian diplomats ask me about my father’s time, to understand what diplomacy was like under the shah, because there aren’t a lot of those people alive now to tell them.

JT: So the shah has been marginalized as a figure of significance in terms of his relevance to the country.

HM: Absolutely, which is one of the reasons why they really don’t care about the shah’s son [Reza Pahlavi], who claims the Pahlavi throne and sits in Washington, D.C., and goes to Congress every now and then and wants to start a revolution in Iran. Not only does the government not care, but the people don’t care. It’s remarkable how little interest there is.

JT: Why do you think that the revolution has not been more successful in bringing economic prosperity?

HM: Actually, it’s not technically correct to say that it hasn’t. It’s only in recent years that the economy has suffered rather badly under Ahmadinejad. Iran’s economy was actually quite vibrant. A large part of the trouble has to do with the sanctions-U.S. unilateral sanctions and some European sanctions-which have made things like import-export and technology transfer very difficult. That has a trickle-down effect. People don’t invest in the country’s infrastructure because they can’t get letters of credit or foreign loans; and foreign companies don’t invest.

JT: Your book gives the sense there’s a kind of closet openness in Iran about certain things. Among the many rather outrageous statements that Ahmadinejad has made is the denial that there’s any homosexuality in Iran. But then it seems fine for it to exist?

HM: In fact, I was with Ahmadinejad the day that he made that speech, and I said to someone,

“I can’t believe that was translated the way it was.” This is not a defense of Ahmadinejad, but what he said in Farsi was, “We don’t have homosexuality as you do here.” What he meant is that they don’t have a gay-rights movement or an activist gay culture or gay pride and parades in Iran. That doesn’t mean they won’t develop these things—they didn’t really happen in America until the ’60s. But I think that the idea that you can do things in Iran as long as you don’t talk about them is very much a part of the culture.

JT: Would you say that the same approach is taken to the subject of drugs?

HM: Very much so, though the Iranian government has become pretty open about the drug problem in recent years. Opium use is a very traditional, cultural thing in Iran, so the government is actually more open about it than they are about some of the other ills in society. They just don’t want to talk about things that might relate to a Western lifestyle even though they know that Iranians indulge. Because there is no real public life left in Iran-there are no bars and the restaurants are closed early because there’s no liquor allowed to be served—people go and have dinner and then everything retreats behind these Persian walls. It is exactly what Iran was like in the 19th century. The government knows that, and as long as it doesn’t really overflow outside of those homes, they feel like it’s no threat to them. Believe me, there are plenty of people in the religious classes in Iran who drink and then go to Friday prayers. But the government is clever-they know all the paradoxes of their own society.

JT: Something else that comes across very strongly in your book is the sense of Iran as part of a

continuum of the Persian empire.

HM: That’s a very important point because there has always been a confusion in the West about -Islam and about the Middle East and the assumption that the countries are Arab. Iranians very much object to that. They are very proud of their own history, but they have this real inferiority-superiority complex thing about the Arabs and the position of Islam in Iran. One of the reasons why Shi’a Islam is so entrenched in Iran is because it really has allowed the Iranians to distinguish themselves from the Arabs, who are mostly Sunni. The Iranians feel that the West has misunderstood and marginalized their history, which is true to a degree. They feel there’s no knowledge of the greatness of the Iranian people. So that plays a very big part in the Iranian psyche. All this nuclear debate—there’s a very Persian aspect to the way that Iran is handling it, which I think a lot of the Europeans and Americans don’t quite understand.

JT: Throughout your book you come up with very nuanced descriptions of what is really being said in Iranian culture. It is often not articulated literally. There are all sorts of manners and code phrases and parallel ways of saying things. It’s almost as if there were a second language. For instance, when Ahmadinejad notoriously said that Israel “must be wiped off the map . . . ”

HM: That should absolutely not have been taken literally. Very few things that a Persian says should ever be taken literally. [laughs] In that instance, Ahmadinejad was just repeating a quote of the Ayatollah Khomeini’s, which was that Israel will vanish from the pages of time. It didn’t imply that Iran is going to be responsible for that. But I think that one of the reasons that the Iranian government didn’t challenge the translation—which was actually first provided by The New York Times—is that they saw that the reaction from the Muslim third world was positive. It was like, “Iran is the last country standing up for the Palestinians. It’s the last country that will say things that we really feel in our hearts.” I think that there was a bit of playing to that audience.

JT: That raises the issue of the Jews in Iran who, historically, have had a place in the country but who, since the revolution, have for the most part left. And then there is Ahmadinejad’s denial of the Holocaust . . .

HM: It’s interesting because even though a large part of the Jewish community has left Iran, there are still 25,000 Jews living there today. There’s a chief rabbi in Tehran, and there are synagogues and Jewish businesses. There’s a Jewish seat in Parliament under the Iranian constitution. Is there anti-Semitism in Iran? There is. Just as there is in a lot of countries. Is it as marked as it is in other countries of the region? No, I don’t think that it is. Ahmadinejad’s position on the Holocaust was very disturbing, and it’s very sad for Iranian Jews. Many Iranians—including some conservatives—view his questioning of the Holocaust as being really damaging to the Iranian reputation.

JT: You’ve been in a unique position with -being a translator and a sort of guide to Ahmadinejad when he’s in the United States. But is there no one who could show him some footage of the Holocaust and say, “This is not digitally doctored. This actually happened”?

HM: Well, he has since said that he never denied it. He even says now, “I’m not saying that it didn’t happen at all.” As far as most people in the Iranian government are concerned, Ahmadinejad said something very foolish. He hasn’t repeated it, since he’s been told not to. Now, that doesn’t mean that they think Ahmadinejad should be forgiven. As I point out in my book, there are people in Iran who do deny the Holocaust. And those are scary people.

JT: What is disturbing in the long term is that you have a leader of a country who would believe something of that order of idiocy. In fact, you aren’t religious, and you have a devout believer who’s running the country, that alone can be-

HM: Problematic. An interesting thing about the religious people who run Iran is that one of their problems with Ahmadinejad, who they thought would be one of their guys because he’s so religious, is that he actually has some really nutty ideas about religion. He’s too religious. He’s too literal. I mean, there are plenty of people in Iran who like Ahmadinejad’s religious beliefs, just as there are plenty of Christian fundamentalists in America who like George W. Bush’s beliefs. But there are also plenty of people who are very uncomfortable with his overt religiosity.

JT: I think that is connected to the fear of nuclear weapons coming under the control of someone with whom it’s not possible to reason.

HM: I can’t speak for all Iranians, but I think that many of them would be uncomfortable with Ahmadinejad if Iran had nuclear weapons and he had his finger on the button. But the reality is that Iran’s system of government is actually very complex. It has a lot of checks and balances, and neither Ahmadinejad nor any Iranian president would ever have his finger on the button. There are too many people involved in a decision of that magnitude.

JT: And yet history is littered with the corpses that were created by the lack of communication.

HM: I guess it’s possible that someone could ignore all reality and decide to launch something. But from what I know of the Iranian side, I don’t think anybody wants a war. This nuclear issue has turned into a matter of rights for them. You know, “If every other country in the world has the right to enrich uranium on their soil for fuel for their nuclear power plants, then why can’t we, just because we’re Iranian?”

JT: So what do you foresee in the future?

HM: It’s impossible to tell. I mean, we’ve got a presidential election here in America, and the Iranians would like to run out the clock on that. I think that the big issue we haven’t talked about for the Iranians—and, obviously, for the Americans—is Iraq. Iran can be a tremendous help to the United States in Iraq. I don’t think the Iranians have a particular preference for John McCain or Barack Obam—-for them, it’s the candidate who is willing to recognize that they are an important country that can have a serious effect on Middle East peace. That’s the biggest thing for the Iranians. And looking past 2009, if Ahmadinejad is defeated in his reelection bid, then I think things can look up for both Iran and the United States. People know what effect he has had on the economy and on Iran’s reputation, so I wouldn’t rate his chances very highly. That said, I wouldn’t have rated George W. Bush’s chances very highly in the summer of 2004, but he did win -reelection. So it’s impossible to tell. But one would hope that the interests of Iran and the United States don’t have to be so divergent.