q&a

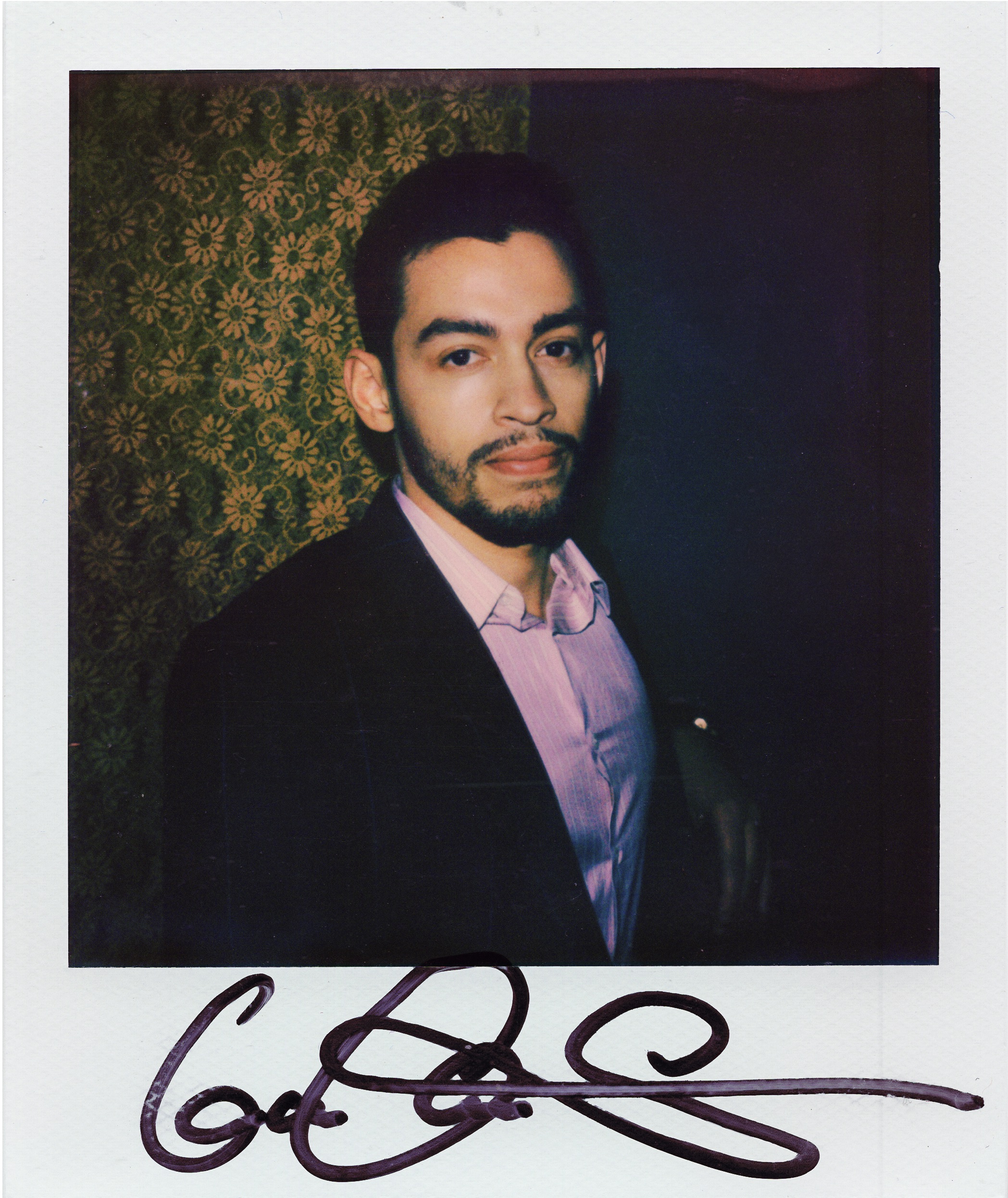

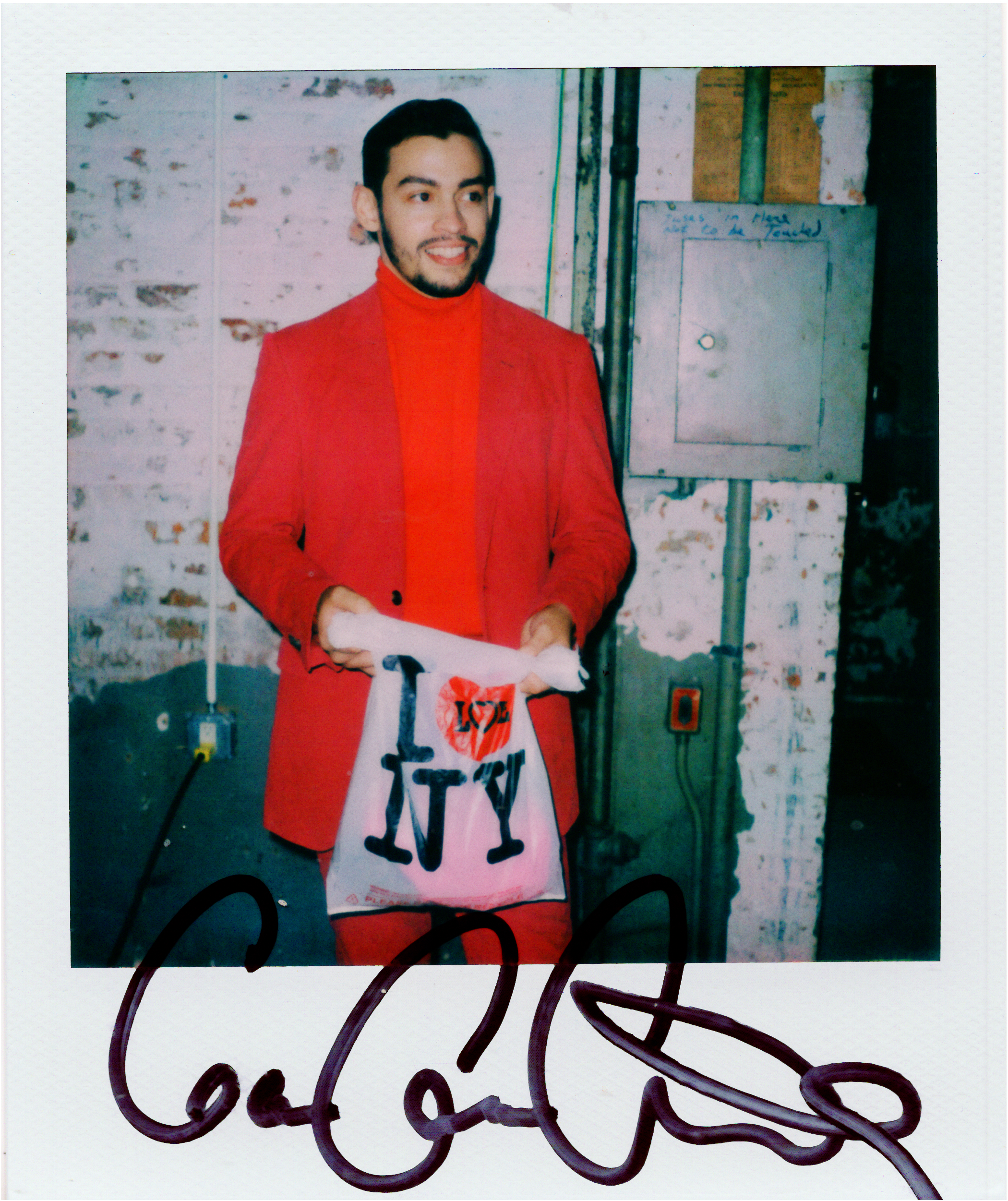

Gabriel Ocasio-Cortez Is Building the Inclusive World He Wants to Live In

Gabriel Ocasio-Cortez. Jacket and turtleneck by GABRIELA HEARST.

For many white people, 2020 was the year that they began unlearning racism. It’s a daunting, lifelong project, to be sure, and that’s mostly because though racism can be evaluated on its jagged surfaces, it is a deep-rooted disease that lives in the mind and heart. Eradicating it requires expansion, a whole new pair of collective glasses with clear lenses, rather than rose-colored ones. In the poem “Song of Myself,” from 1855’s Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman, a white man, wrote that he was a bundle of contradictions, but nevermind those because: “I am large, I contain multitudes.” People of color, meanwhile, are rarely extended the same courtesy for their own multidimensionality. This past summer, America witnessed a series of nationwide uprisings supporting Black Lives Matter amidst a pandemic, protesting ongoing police brutality and systemic violence against Black and brown people. However, people of color are so much more than the oppression they face. They contain multitudes.

Gabriel Ocasio-Cortez—the younger brother of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 31-year-old, history-making Democratic Congresswoman representing the 14th district of New York—knows these truths to be self-evident. He’s her biggest fan. He’s also an ascending artist and musician, an advocate for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing, a voice for ending homelessness, a queer liberation activist, and a native New Yorker with Puerto Rican heritage. He’s been told he looks like a young Marc Anthony—by the one and only Cardi B, no less. He’s a free-spirited, forthright and strong-willed Sagittarius who cares deeply about ensuring those who share his lived experience have the support and community they so richly deserve. At times, he’s had to build himself up from ground zero, having lost half his hearing and his father as a teenager, leaving him to help fend for his family. Nevertheless, Gabriel’s story is one of the transmutation of personal experience into a vehicle for helping others. For example, when he first began to lose his hearing as a teenager, Gabriel taught himself guitar and piano, which he still uses to compose his own original music. Years later, his passion has evolved into a Deaf-centered arts collective, Deaf Collective, which he is turning into a nonprofit.

On a brisk late-November afternoon in New York, I met Gabriel at Washington Square Park to sip lattes and discuss his life’s work, his upbringing, his sister’s rise to fame, and how his life has changed as a result. As a queer Black artist who has also built myself from scratch, I have so much in common with Gabriel. He too has overcome seemingly impossible odds to become an agent of change, a tireless co-creator of the inclusive world he wants to live in.

———

MICHAEL LOVE MICHAEL: It appears that you juggle so much between being an artist, activist, and community organizer. And these days, it seems that standing up and owning our points of view is paramount to the progression of culture and society. Would you agree?

GABRIEL OCASIO-CORTEZ: We’ve had so much time lately to reflect as a culture. Each of us is having a long overdue “Man In the Mirror” moment, if we’re paying attention. Being saturated with a lot of activism, it is easy in this day and age to be overwhelmed, but the reality is that if you are not going to pioneer something or campaign for something, the problems we face are just not going to go anywhere. If I am not actively fighting for change, I am going to feel helpless. Being a voice for others is the only way that I am going to ever really calm my own nerves.

MLM: Was fighting for the things you cared about part of how you grew up? In other words, have you always been a kind of activist, even before you knew what that was?

GOC: I think so, but fighting for the things we cared about back then was a little bit more survivalist. What we cared about was keeping a roof over our head, and when you grow up fighting for yourself, it makes it easier to fight for others, because you know how to at least play defense, and then as you master defense, you can get on the offense. Looking out for other people is also being on the offense for yourself ultimately.

Jacket and button-down by LANVIN.

MLM: I know what you mean. It’s like discovering a higher purpose beyond yourself, understanding that your liberation is tied to the liberation of all, and vice versa. How do you embrace the parts of you that are vulnerable?

GOC: It is funny because I think some of the sweetest people have had to fight for themselves, no matter how hard they try. It is so hard for them not to be the heroine, but the reality is that even the greatest superpowers sometimes are hollow. I grew to love failure—that is something recent for me. I was 15 when my dad died. It was a very progressive, degenerative, visible decline for two years, and I remember having this overwhelming feeling of doom, knowing that when he passed we would all be free of this constant worry and fear. But then the fear came back tenfold, as he was the main provider. Where were we going to live? Where will we be? He wanted to take his family, put them somewhere safe, and get his kids out of the Bronx, and at least that came to fruition, but there was more going on at the same time that made it all so hard.

MLM: What else was going on?

GOC: I also lost half of my hearing, and it was just like I literally had no sense of direction when it came to sound or even when it came to my life. I was also coming to terms with my sexuality and wanting to come out, but always having the fear, a very valid fear, that I would be rejected from my house. [Because of my sister], many people assume that there were many progressive values in the way we were raised, but the reality is that we were righteous when it came to our beliefs and morality about class. My dad instilled in us that we would have to always be ten steps ahead, had somebody passed the ladder back down.

MLM: That’s all so stressful. I grew up similarly. For me as a Black person, internalizing the idea that you have to be “twice as good” as a white peer in order to survive or even make it half as far in life, is certainly its own kind of burden.

GOC: Precisely. Add to that, at the time, I am like 15 going on 16 years old, and scared of being homeless because they were going to foreclose on our house. I immediately had to start working, start hustling, doing things that are not necessarily done in daylight in order to obtain income for the sake of trying to keep our day-to-day going, but at the same time, still not being able just to be myself. So it’s like, what do I do? Do I become homeless with my family or without my family? These were the things going on in my head, and that was my reality for a long time. I did not feel comfortable coming out to my family until I was 150 percent financially stable because I felt that it was just simply going to rock the boat to launch.

MLM: That’s so tough. I understand that choice—of needing to withhold something really important about yourself until you knew without a doubt that you could take care of yourself. That’s something most people never have to experience.

GOC: Right, and it’s not necessarily the right choice. The right choice is always going to be situational. My story is never meant to be a how-to guide.

MLM: A moment ago, you said you weren’t afraid of failure. What does that mean to you exactly?

GOC: I had that fear of just having the carpet pulled out underneath me for so many years in a row. When my sister got elected, it did pull the carpet out underneath me, and at the time, I was a real estate broker. I was very successful. I was really proud of the business that I had built, and when I nominated my sister for a Congressional bid to run, I remember thinking that I always knew she could do it. There was never a question about it. For me, it has always been a matter of fact. I am not surprised by who she is. This is the person I have always known, and the reality is that before I hit send on that letter, I remember thinking to myself: this could fuck shit up.

MLM: Fuck shit up in a good way?

GOC: Meaning that this could be a direct threat to my safety. This could be a direct threat to my family.

MLM: Because Alexandria would instantly become a public figure.

GOC: Exactly. I could lose my business. I definitely weighed the fact that every facet of my life that I considered positive could go negative, and everything that I took for granted could be flipped. But I believe people like my sister are everywhere; people with her goodwill and brilliance are all around us. The problem is that often, as a society, we do not spotlight the right people and we do not believe enough in ourselves to change anything for the better. Alexandria did believe in herself, and so did I.

MLM: How did her rise to fame affect you?

GOC: When she first started getting a lot of attention, I got a call from the FBI saying that I could not open my mail because there were mailing bombs. We do not have any address out. It is definitely tricky. I had to stop working because I could not post open houses as a real estate broker, because people would come and be weird. People would wait outside, and it got to a point where it was genuinely overwhelming. I would say it definitely splintered me. I actively worked as much as I could for a few months just to try to save as much as I could, and I basically had to quit because it was what I had projected as my worst-case scenario. But was it worth it? Yes. I had already been through so much, I thought it couldn’t be as bad as it was when we were about to get foreclosed on. I didn’t know it would be a thousand times worse, but I am so grateful for it because I needed to lose my mind. I needed to allow myself to fail, and I did. I quit. I burned out. I moved. I changed everything.

MLM: That’s wild. But on the flip side, I read once that you said that it was Alexandria who gave you faith in government that you hadn’t had before.

GOC: It’s true. I never felt represented in government. I have never felt cared about by the system. I never saw a cop that I trusted. There was nobody on the government payroll that gave me any type of joy, but once she got involved in politics, it was the first time I ever felt hope in the government. It’s one way I knew I was doing the right thing by supporting her.

MLM: The last four years have been difficult in terms of division within political parties. While Alexandria has been a lightning rod for younger Democratic voters, what do you believe can still be done to unite Democrats?

GOC: Perhaps it will change with Biden in office, but I still think the Democratic party is totally splintered at the moment. Luckily, we’ve been able to get through this past November, but there is just so much finger-pointing in the party. There can be an incumbent who is choosing to campaign on stances that are repeatedly proven to lose elections, and then they lose the elections and blame young progressives.

MLM: The youth are often accused of being apathetic about politics, especially young progressives. What sorts of organizing efforts would you like to see take place to help shift that perception?

GOC: Well, how are you going to create a lasting snowball effect for the power of the party if you cannot appeal to the people who are going to carry the torch? I think that the Democratic party is so bought and paid for. I think both parties are, to be extremely clear. But trust: corporate America succeeds regardless of who exactly wins. It is just perhaps different sectors.

MLM: That’s a fair point.

GOC: The reality is that we need to get corporate money out of the election—out of elections, period. You need to get corporate money out of politics altogether, and then people are actually going to see politicians running on actual stances that affect our communities because the communities are going to be the number one priority.

MLM: I’d like to think that with this incoming president, the tide is shifting toward greater accountability.

GOC: Exactly. Even once Joe Biden is sworn in, anybody that has been paying attention knows that you still have to hold him [and Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris] accountable for everything that they’ve said. Even if you are just looking at student loans, then you have a vested interest. If you are looking at the fight for the equality of Black lives, you have a vested interest. If you look at anything that our generation distinctively cares about, then you have to aggressively campaign for that president’s administration to care, too.

Pant by GABRIELA HEARST.

MLM: Have you been asked about running for office yourself?

GOC: Yeah, for sure.

MLM: What is your answer to that question?

GOC: It’s interesting. That question is always paired with some question or comment about the Kennedys. I understand how hopeful my sister makes people feel, and I think that is something really special and sacred. I bring up the Kennedys because it was another time back then when people felt really hopeful. That said, I would never want to win an election just because of my last name. And I do not want to encourage and further set the precedent of family dynasties in politics.

MLM: We’ve been talking a lot about how the country could be run. What are your hopes and dreams for the communities you’re specifically part of?

GOC: For me, it is about getting people into more of a mindset to create organizations. I think people are starting to wake up, but there are many more steps. You still have to look at your immediate community. You have to look at your zoning board. You have to look at the things that are directly affecting you. But for me, to practice what I preach, I created Deaf Collective, which is going to be an organization that is applying for nonprofit status and is going to be essentially a gallery and a spotlight for Deaf queer talent. It is going to be a fundraising platform to go ahead and pay for sign language classes, direct-to-you grants, and scholarships—you have so much visibility in the queer community, especially right now. But when you think about Deaf representation it’s fractional, even though we outnumber the queer community in the U.S. When you think about representation in the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community, you might think of someone like Nyle DiMarco or Deaf U—which is great. However, considering we outnumber the queer community, we should strive to get to their level of representation.

MLM: So how do we broaden the scope of understanding how Deaf and hard-of-hearing people can be represented more fully?

GOC: You start asking questions. How are the Deaf and hard-of-hearing being represented in our architecture? Where is it in our visibility of others? Where is it in public health and safety initiatives? And the reality is that you have twice as many people who are Deaf and hard-of-hearing than you have queer Americans. There are about five percent of Americans who are openly identifying as queer, which likely means more, of course, and about ten percent of Americans are Deaf or hard of hearing, so the margins are way off in terms of visibility. You also have huge numbers of mental illness and severe depression for people who are Deaf and hard-of-hearing, and I experienced that. You are less likely to ask people to repeat themselves because you are tired of asking people to repeat themselves, and people get tired of repeating themselves. You are tired of not hearing that joke that everyone is laughing at. You miss the train because you did not hear it. It’s all these things that start to snowball, but if you are partially still hearing, then it just might not be enough of an issue for you to go ahead and learn sign language, because you are not integrated in the Deaf community. Each of the problems—along with, say, if you’re part of the queer community, too—it can be almost too much.

Trench and button-down by COACH.

MLM: I am just taking it all in. When you were talking about the intersection of challenges that you and other members of the Deaf and hard-of-hearing communities face, I got curious about what helps you counteract depression or feelings of hopelessness that may come up.

GOC: I think happiness is a daily struggle. I do not feel the need to pretend that I am overflowing with an abundance of joy and happiness when I am not. And as queer people of color, we are taught that in order to be palatable, we have to be outwardly joyful. We are more likely to be accepted and loved and integrated if we are on-demand quirky. These days, if I am having a bad day, I am going to tell you because telling you is going to make me feel like I am communicating. It all comes down to language, the ability to empathize with and understand one another.

———