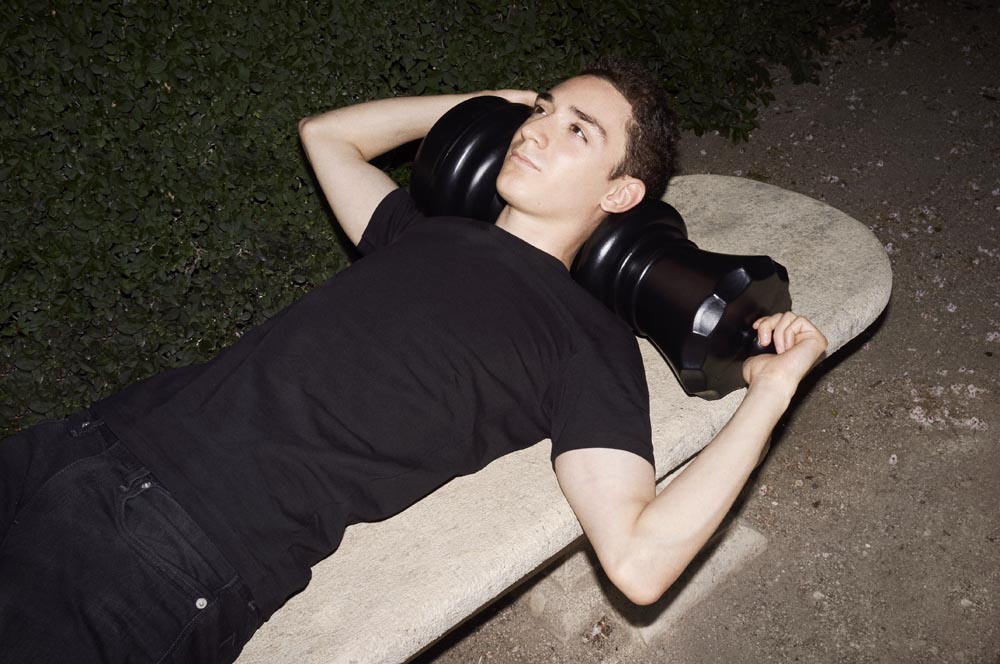

Fabiano CARUANA

Fabiano Caruana calls it a “nonviolent war game,” and he happens to be number two at it in the world. In the last few years, professional chess has experienced a youth explosion—not least of all because Norwegian champion Magnus Carlsen was a mere 19 when he ascended to world number one in 2010. But right behind him and closing in fast is an intrepid master at strategy who, at 23 years old, has won tournament after tournament and is the leading contender to become the United States’ first world champion since Bobby Fischer in 1975.

Caruana, serious and direct and showing zero arrogance considering the list of words that often circle his name—words like prodigy and genius, chess being one of the few realms where those designations actually apply—came to the sport the way most kids come to hobbies: an after-school program at the age of 5. “I was a decent student but had some disciplinary problems, and they thought that would help me out,” he recalls. Caruana, born in Miami and of Italian descent, played casually—international tournaments here and there—until the age of 12, when his family moved to Madrid. There, he devoted himself to chess full time. At age 14, he became a grandmaster. And while one assumes that Caruana must have been some sort of calculating supercomputer in teenage form, he admits, “I was never really interested in mathematics.”

Caruana, who considers Fischer something of a hero, spends much of his time training: “I like to play and practice and look at games that are being played every day.” He also keeps in physical shape, swimming, jogging, and playing soccer. Athleticism is a surprisingly crucial aspect of the game; when asked why chess has been dominated by younger players, Caruana speculates, “As physical fitness becomes more and more a part of chess, players are starting to realize that one of the strategies is to tire out your opponent. The trend is to keep pushing and try to make the most out of whatever slight edge you might have.”

This past May, after ten years playing for Italy, Caruana decided to switch affiliations and join the United States Chess Federation. The announcement caused a stir, with rumors of the superpower buying up top champions, but the young player dismisses the conspiracy mongering. “I have always felt like an American,” he says. “And I wanted to go back to the U.S. because I have family and friends there. When I changed federations in 2005, I was 13 and the chess scene in the U.S. was not as good as it was in Europe. Now it’s improved so much. It seems like the right moment to go back.”

As I spoke with him, he was preparing for a tournament in Norway featuring ten of the world’s top players—including Carlsen. “There’s pretty much only good relations between the top chess players,” Caruana says. But true to a man who has made a career out of thinking a dozen moves ahead, he adds, “Most of all, they’re competitors. Their job is to beat me, and my job is to beat them.”