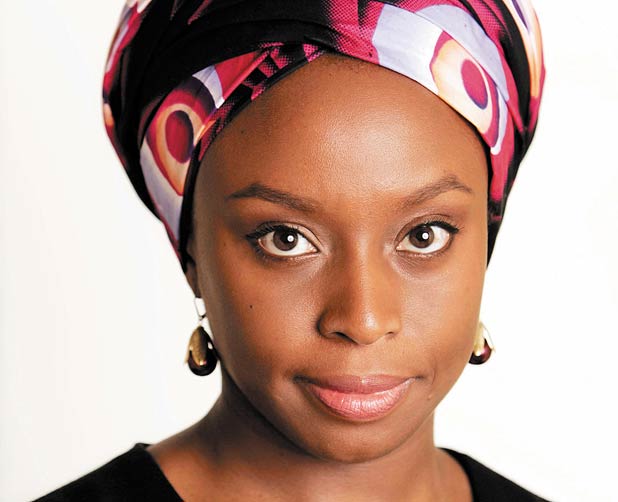

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Continental Divides

ABOVE: CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is not a writer at loss for a word, a thought, a next move. Her assured and humbling career owes to the continued spark of a lifelong curiosity with the people of post-colonial Nigeria. The author and 2008 MacArthur Fellow first attracted considerable attention a decade ago with her haunting debut Purple Hibiscus. Sophomore effort Half of a Yellow Sun confirmed early promise with prestige, all for which she is gracious and little for which she probably cares, really. Her unflinching, multi-arc redemption stories bridge the gap between Africa and the West, in a vein perhaps only comparable to that of the late, missed Chinua Achebe. Here is a precise author compelled and suspicious, like the great ones are, of lasting happiness on and off the page.

After two novels chronicling familial and political upheaval in her native Nigeria, Adichie goes abroad for her new book, Americanah (Knopf). The author’s fiercely clever stand-in, Ifemelu, follows the racial indignities she encounters as a college-educated African immigrant in the US with an uneasy return to Nigeria and her old flame, Obinze, now married and wealthy yet unfulfilled. Spanning the borders and histories between these two outsiders, Adichie defines the sum of disparate cultures with new clarity, while questions of identity and love remain elusive as ever.

JOSEPH KLARL: You and Ifemelu are both Nigerian writers, both Igbo, you both had fellowships at Princeton. Americanah even includes a meta-narrative of Ifemelu’s blog posts on American-Nigerian relations. How much of Ifemelu is you?

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE: I can write with authority only about what I know well, which means that I end up using surface details of my own life in my fiction. There are bits of me in Ifemelu, as there are in most characters I write. I find her more interesting than I find myself. And I don’t agree with everything she says.

KLARL: Many of your characters are defined by their unease with social pressures. Notably, Obinze hates the elitism and pretense that his wife enjoys, but even going back to your debut, young Kambili lives under the rule of her perfectionist Papa. How has this feeling manifested itself in your life?

ADICHIE: I think it’s possible to have been a happy child, as I was, and still question and push back with regard to societal conventions. I am a person who believes in asking questions, in not conforming for the sake of conforming. I am deeply dissatisfied—about so many things, about injustice, about the way the world works—and in some ways, my dissatisfaction drives my storytelling.

KLARL: With each of your novels focusing, in part, on social issues—Purple Hibiscus and fundamentalism, Half of a Yellow Sun and the Biafran War, Americanah and race relations—do you also feel a responsibility to educate as a storyteller?

ADICHIE: No. I think human beings exist in a social world. I write realistic fiction, and so it isn’t that surprising that the social realities of their existence would be part of the story. I don’t believe that art and politics or social issues must be separated. In writing about marriage, for example, money can be a big factor, and money is linked to earning, and earning is influenced by politics. Would the story of a marriage of a middle-class couple during the Great Depression be different from the story of a similar couple in boom economic times?

KLARL: After covering past and present Nigeria in your first novels, I wonder if there was a conscious effort to include a greater influence from abroad in Americanah.

ADICHIE: Each of my novels has come from a different place, and the processes are not always entirely conscious. I have lived off and on in America for a number of years and so have accumulated observations, found things interesting, been moved to tell stories about them.

KLARL: The dichotomy you describe between Princeton and Trenton in Americanah reminded me of Manhattan and the African community in the Bronx—how little neighbors, even in diverse cities, know of each other. Is it important as a writer to experience both Princeton and Trenton?

ADICHIE: I’m not sure. I’m equally interested in the writer who knows only one or the other. For me, it is important, on a personal level, because I am interested in many stories, in how people experience life differently.

KLARL: While Ifemelu is sympathetic to ostracized people, she also screens the names of African taxi drivers to avoid awkward encounters with fellow Nigerians. Though American prejudice toward Africans is readily apparent to you, do you find new prejudices of your own developing in America, specifically toward native Nigerians?

ADICHIE: I think every immigrant group in a new country has strong inter-group prejudices as well as connections. There are Nigerians who have become friends of mine in the US and would never have been in Nigeria. And there are Nigerians in the US I am very keen to avoid as much as is humanly possible.

KLARL: Is your method of using non-linear narratives useful to you when writing about political turmoil? It seems to accentuate the fickleness of class, status, even country, by hinting at changes quickly and mysteriously.

ADICHIE: Yes, I like that reading.

KLARL: On that underlying uncertainty—in your books, the lavish Nigerian compounds of the rich are never as secluded and safe as they appear. Even characters living in them know this.

ADICHIE: I think the wealthy in Nigeria, particularly in Lagos, because it is the urban center, are aware of a certain precariousness in daily life, but not in a terribly ominous way.

KLARL: Are you an optimist?

ADICHIE: I am a strong believer in the ability of human beings to change for the better. I am a strong believer in trying to change what we are dissatisfied with. But I am also wary of excessive cheeriness, too much of what is often called “positive thinking,” because I think it can often become a way of not fully and honestly engaging with things.

KLARL: I’m reminded of the rains coming near the end of Purple Hibiscus, to bring new hibiscus flowers after so much grief. This was indicative to me of an endless cycle of peace and violence. How do you feel about Nigeria’s future and modern efforts toward democracy there?

ADICHIE: For me, the rains meant a sense of small hope for Kambili and her family. If you take a long-term historical view, Nigeria is a very young country. Democracy takes time to evolve. Nigeria was formed from a dictatorship—British colonialism—and underwent homegrown military dictatorships. Now, we are emerging. It is going as it should, in fits and starts, but it will evolve for the better.

KLARL: Having developed this new novel from a short story, and as a follow-up to your 2009 short story collection The Thing Around Your Neck, what is the continued appeal of short fiction for you?

ADICHIE: I love short stories, as a reader and writer. Some of my greatest pleasures as a reader have come from short stories. My friend Nathan Englander‘s recent collection is an example.

KLARL: What other authors—from both Nigeria and the West—should Americans be reading?

ADICHIE: There are many Nigerian authors whose work I respect—Gabriel Okara, JP Clark, Tanure Ojaide, Eghosa Imasuen, Lola Shoneyin, Chika Unigwe, Helon Habila, Uzodinma Iweala. And also too many non-Nigerians to name. I am presently reading and loving Meg Wolitzer, Tash Aw, Christopher Wiman, Emily Raboteau.

KLARL: Ifemelu dislikes the novels favored by her ex, Blaine, written by vain young men and filled with pop culture nuggets. Your writing is decidedly more personal, but you mention a lot of books—Jean Toomer’s Cane, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, William Faulkner’s Light in August, among others. Are you creating a path for your readers of what to indulge and what to avoid?

ADICHIE: I would never presume to tell people what to read and what not to read, although of course I would love it if everyone loved the books I love. For me, this novel is also about the love of reading, about the power of books. Obinze is formed by his reading, Ifemelu comes to love books and understand their power. Books became her consolation. So it’s less about creating a path for my readers and more about simply celebrating my own very personal love of books. I love Baldwin and Faulkner; I admire but don’t love Cane.

KLARL: Your last two novels have included characters’ blog titles, chapter outlines. Chinua Achebe’s famed Things Fall Apart ended with a proposed book title, too, but a sinister one: The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger. Considering the old phrase about history and victors, can writers use mass communication to take history back?

ADICHIE: Yes. Absolutely. History is always a contested space, and writers can claim their own portion of space by writing.

KLARL: After Achebe’s recent death, readers may feel you, as a prominent Nigerian author in America, bear some symbolic torch with his passing.

ADICHIE: I think the world lost one of the last truly great human beings, and I don’t often use that word, “great,” to refer to people. Achebe is the writer whose work is most important to me. His novels gave me permission to write. Arrow of God is a novel I can always depend on to give me satisfaction and pleasure.

KLARL: Chinua Achebe had his “African Trilogy.” At this point in your life, does Americanah feel like an ending or a beginning?

ADICHIE: Something scary about this question! Hopefully not an ending. But the true answer is neither, because I don’t think of my work in those terms.

KLARL: During your TED talk on “The Danger of a Single Story,” you spoke about the children’s books you enjoyed, how they inspired you to portray your own reality. Between those early stories and Americanah, what has kept you writing?

ADICHIE: Watching the world. Observing people. Reading. Dreaming. Hoping.

AMERICANAH IS OUT TODAY.