Lucid Dreaming with William Buchina

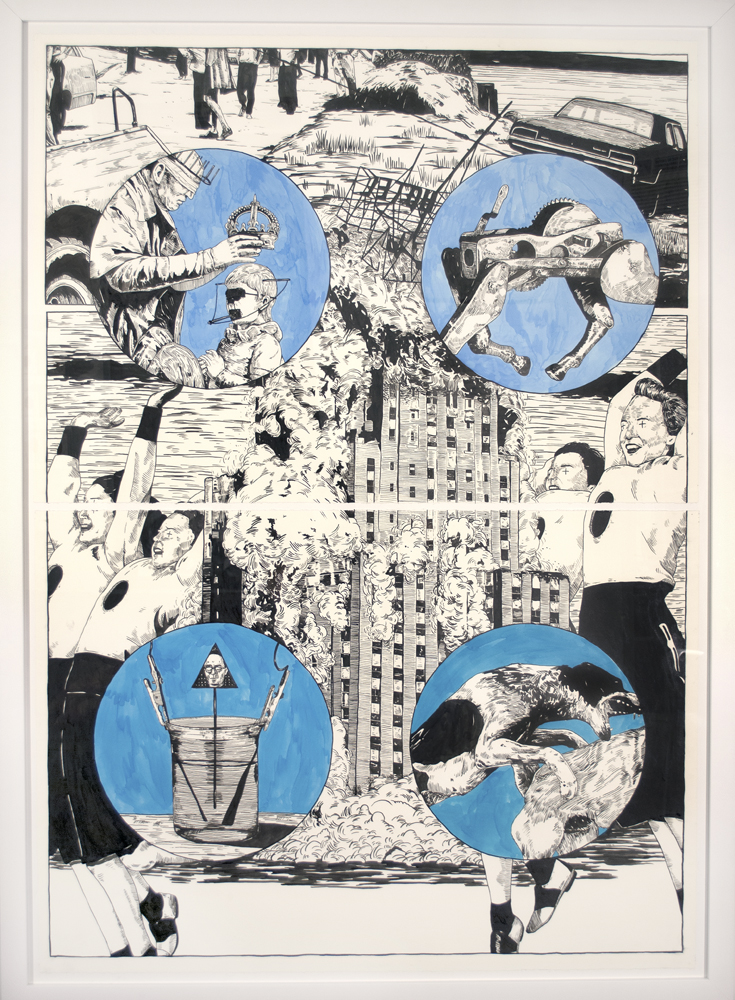

Take a scenic drive 30 minutes north of the “World Famous” Roscoe Diner in upstate New York, and you’ll soon find yourself amidst the rolling hills, silos, and cow-peppered milk farms of Treadwell, where the soft-spoken visual artist William Buchina has been steadfastly creating new works for his exhibition “Lower Than the Lowest Animal.” Opening April 4 at Garis & Hahn, the show features a collection of highly detailed surrealist paintings that evoke comparisons to M.C. Escher, Salvador Dalí, and Robert Rauschenberg. Each piece is a fractured glimpse into Buchina’s psyche, itself a treasure trove of occult imagery collected over the last decade and re-appropriated with the same eye for composition as Ray Johnson, Buchina’s favorite collage artist. Done in India ink, the paintings unfold like kaleidoscopic dreamscapes, with mysterious illustrated vignettes framed within floating circular windows that intercept the canvas’ harsh perpendicular lines. Taking Buchina’s style, subject matter, and comic-book panel composition into account, comparisons could also be made to Eddie Campbell’s stark line work in Alan Moore’s ambitious graphic novel from the early ’90s, the Jack the Ripper horror anthology, From Hell (Kitchen Sink Press).

Buchina speaks quickly, but with a hushed and somewhat indistinguishable accent, having traveled extensively across Europe and Asia before returning to New York from Istanbul in 2010. He shares his current studio—a towering, light-suffused red barn waiting for its water pipes to unfreeze—with his charming longtime girlfriend, the Turkish artist Sinejan, who moves through the space like a young and ethereal Maria de Madeiros, who beautifully portrayed Anaïs Nin in Philip Kaufman’s 1990 film, Henry & June. This is fitting, of course, as Buchina’s last show was titled, “Lust, Crime, and Holiness” after a passage in Henry Miller’s lurid masterpiece, Tropic of Cancer.

KURT MCVEY: Where did you get the title of the new show, “Lower Than the Lowest Animal?”

WILLIAM BUCHINA: All the titles come from books.

MCVEY: Was this also from Henry Miller?

BUCHINA: No, just the last show (“Lust, Crime, and Holiness,” 2013, Garis & Hahn). This time I was in Massachusetts for a friend’s wedding. I was staying at her mother’s house. I left the wedding early, went back to the house, and climbed up to the attic where I was sleeping. I came across this old book—maybe from 1910 to 1920—and it was about morality. It was more of an instruction manual, actually.

MCVEY: Do you remember the name of the book?

BUCHINA: No, the cover was ripped off, though it did have many great illustrations for each chapter. One chapter was called “Lower Than the Lowest Animal,” and it was about people who succumb to vice. Of course, a hundred years ago that meant having a couple of drinks or having sex outside of marriage, things like that. In any case, it was a very lofty guide, basically on how to be the very best Christian you can be. I saw, “Lower Than the Lowest Animal” and I immediately wrote it down, as I do pretty often with everything I read. That was almost a year ago, and I’ve been dying to use it ever since. I actually ran it by Max [Teicher, Buchina’s dedicated young art dealer, friend, and manager], and he was like, “No. Please. No.” [laughs]

MCVEY: I appreciate artists that “go for the jugular,” as I like to say. People like Henry Miller, for example. I also enjoy these really intense classical engravers, like Gustave Doré, who illustrated Dante’s Inferno, a text that is literally about exploring the deepest, darkest depths of the human experience. Like you, his attention to detail is impressive.

BUCHINA: Thank you.

MCVEY: You spoke about vice earlier, and I assume this is the case for many artists, but how much of your art is an outlet for the darker corners of your psyche?

BUCHINA: That definitely has a large influence on the things I choose to paint. I’ve always been like that, and it’s always confused people who know me or are very close to me. When I was a kid, I would draw extremely violent images all the time, but I was always very calm and lived a very happy life. I never showed these emotions any other way, just in my art.

MCVEY: You were talking about vice, what are some of your vices?

BUCHINA: Well, I’ve put some thing behind me, in my getting-on of years. [laughs] No, no substances or anything like that. Though I do like to read dark things.

MCVEY: What have you been reading lately?

BUCHINA: I’ve been reading a lot of science fiction, specifically works by Arthur C. Clarke and Phillip K. Dick, which I always thought I wouldn’t be into. I just read The Man in the High Castle by Dick. It’s about an alternate World War II outcome where the Axis powers win the war and divide America between them. I only now discovered how beautifully absurd these books are— just fantastic, in the dictionary sense of the word.

MCVEY: Tell me about some of this re-appropriated, occult World War II imagery in some of your work.

BUCHINA: Well, in high school, I couldn’t be bothered with reading books. I just didn’t care at all. After I graduated, my father was attempting to get me to read. Like many people’s fathers, my dad was really crazy about World War II, also he was of that generation. He’s 80 years old. For about three years, I read nothing but the World War II books that he had given me. I also watched pretty much every documentary there is on the war.

MCVEY: World War II still seems to have the most iconic imagery. It is by far the most cinematic war.

BUCHINA: Because things changed very drastically right after that. You never saw another horse in a war. Also, the technological leaps were just massive in scale. The whole war was massive. The uniforms were beautiful, a lot of the machinery, as horrible as it was, if not beautiful in design, was at least interesting to look at. So when choosing images to use or appropriate in some way, I do instinctually go back to that era. I’ve tried more recently to mix it up.

MCVEY: Nothing is a direct allusion. You give the viewer just enough to create their own narrative within this strangely familiar aesthetic. I wanted to tell you, your paintings kind of reminded me a lot of these dreams I’ve been having lately.

BUCHINA: Really? [both laugh]

MCVEY: It’s these images, within images, within images. Also, I always seem to be moving through a large, dilapidated, multi-room space, with this lurking threat of a potential global war or catastrophe on the immediate horizon. [laughs] Tell me, though, do you dream often? If so how much dream imagery makes its way onto the canvas?

BUCHINA: I do. The shame of it is, I do dream quite vividly, but as soon as I wake up, it’s already receding into the distance at a phenomenal speed. This is quite common, of course. Before I commit anything to canvas, there’s this long period where I just pour over all the images I’ve collected. So I’m constantly looking at this stuff, and it’s sticks with you and you wind up seeing it when you close your eyes. You see it everywhere.

MCVEY: I look at your work and I see a lot of Escher and Dalí. I also see some elements found in films by Alejandro Jodorowsky.

BUCHINA: That’s interesting. I did a commissioned piece a couple months ago that lifted an element directly from The Holy Mountain. That’s another place I get a lot of imagery—watching films. Have you seen the R. Crumb documentary?

MCVEY: Crumb? Yeah, it was great.

BUCHINA: He shows a photo album full of source material. He’s got tons of them. It’s funny. [points to an image of power lines on one of his pieces] He was talking about power lines, and he was like, “You can’t make this shit up. You need the source material.”

MCVEY: Are the power lines a direct homage to Crumb?

BUCHINA: I don’t know. Yeah. Probably. I have been collecting images for almost 10 years now, but I was always focused on the focal image, not the background. You never focus on the little details, like this thing [points to a power outlet in the corner of the room] with the rust and the missing screw. I couldn’t pull something like this from my memory and draw it well.

MCVEY: I notice a lot of these mundane, trivial objects as well, and this may be a little morbid, but it often makes me think of my own mortality. This one millisecond you take to look at an old insignificant power outlet in the corner of a barn in upstate New York is very much apart of my larger experience. Did you see Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life?

BUCHINA: I did, in the theater. It was very much like a dream.

MCVEY: The film ends on this seemingly random image of what looks like the Verrazano Bridge. It reminded me of drives I used to take as a kid upstate—not unlike the one I took earlier today—looking out the back window of my parents’ car and seeing all these things going by. I wonder, if your life was flashing before your eyes, moments before your death, how likely would it be that the last image you saw was something so random?

BUCHINA: I have really strange memories, and a very strange lack of memories, also. I search for things I maybe should have remembered—significant moments—but instead I remember these things that are odd in their nothingness. I remember I used to be obsessed with junkyards. I would beg my parents to stop the car so I could stare at these crushed cars. I don’t know why, but I once asked my parents if we could have a picnic in a junkyard. [laughs]

MCVEY: [laughs] What did they say?

BUCHINA: “That’s the stupidest thing we’ve ever heard.” [laughs] To me, they were so beautiful. For example, my girlfriend and I just bought this old used car, and I was joking with her that if we ever actually move up here permanently, I would love to drive that car way out into the hills behind our house and leave it there. [laughs]

MCVEY: Let it become part of the landscape.

BUCHINA: The grass grows through it, little animals get in there, and people hate it. They think it’s so trashy, but I think it’s really nice! [laughs] It’s open to interpretation. In a way, it’s similar to the narrative I create for strangers who drive by in their cars. Who is that? Where are they going? Will they have a baby in a year, or commit suicide in a week? I can make up anything I want. I don’t want to know the truth. I like confusion. In the few times I’ve shown, I’ve really enjoyed standing off in the distance and watching someone critique one of my pieces to a friend. I always think, “Whatever that person is saying, whatever they think, they’re right. They’re right.”

“LOWER THAN THE LOWEST ANIMAL” OPENS APRIL 4 AT GARIS & HAHN.