Notes on Sue Tompkins

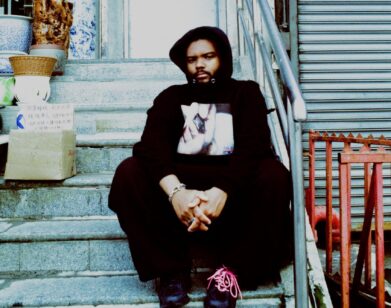

“I probably protect myself by not asking myself too much,” artist Sue Tompkins says when we meet her in Lower Manhattan. “I don’t analyze too much, because then I’ll question, ‘Why do I write down all of these random little phrases?'”

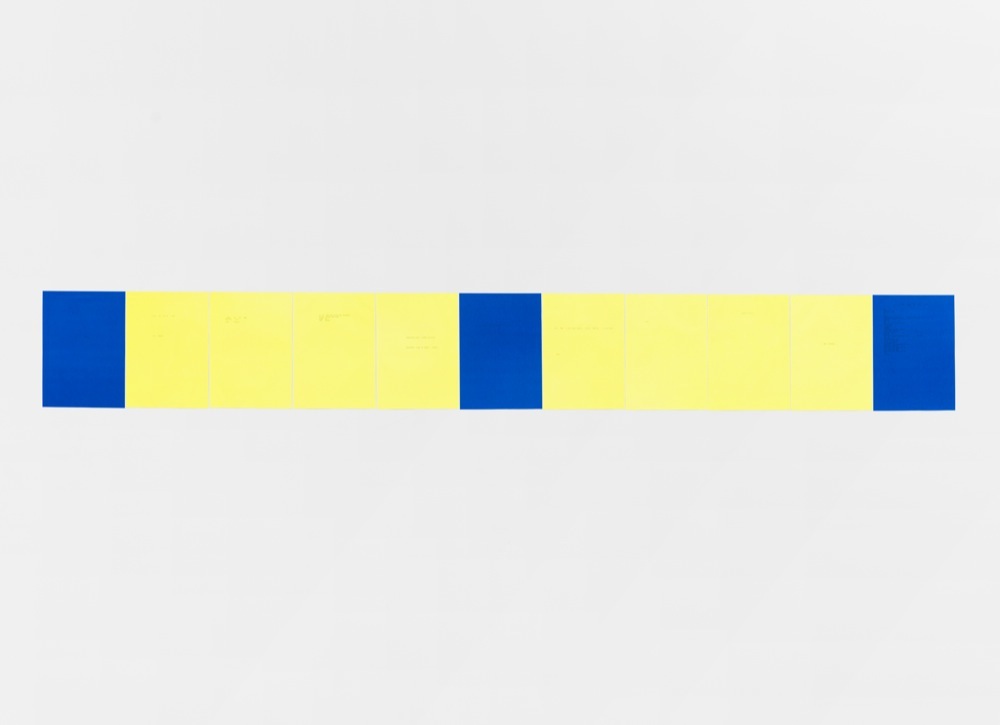

The random phrases to which Tompkins refers eventually compose her performances and text-based works, which are now on view at Lisa Cooley in New York. The British artist uses a typewriter to deliberately space and cull together phrases like, “Can we,” “Get born out,” and “Come on.” Through repetition and re-contextualization, attention is drawn to what the phrases mean, and more so, what they lack. The title of the exhibition, “When Wayne Went Away,” furthers these notions, evoking thoughts about who Wayne might be, as well as what happens to him and the viewer when he disappears. Tompkins continues, saying it’s like, “Has the right person walked out of your life and you’re like, ‘Yay!’ or has the wrong person walked out and you’re gutted? It sounds extreme, but I’m trying to suggest that in the title.” Small, abstract paintings and three draping pieces of chiffon, each adorned with one zipper and safety pins, accompany Tompkins’ text works. During the opening weekend of the show, she also gave two live performances, arguably the most well-known aspect of her practice.

Following graduation from the Glasgow School of Art (where she is still based), Tompkins joined the now-defunct indie rock band Life Without Buildings, where she says she truly found her voice and ability to perform. “I was allowing myself to sing and speak and write for the first time,” she recalls. “I hadn’t really had that much purpose before.” Upon its collapse in 2002, she began performing as a sound- and vocal-based artist on her own. She has now shown and performed throughout Europe, in cities such as London, Oslo, and Copenhagen, but “When Wayne Went Away” marks Tompkins’ debut U.S. solo show. We met her at Lisa Cooley, when she was installing the works, to learn more.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: Can you tell me about how this show came to fruition?

SUE TOMPKINS: Lisa came to Glasgow to visit me about a year ago and she mentioned having a show then. It was finalized at the end of last year, and I arrived yesterday. It’s such a basic thing, but I’m one who needs to be in the space [for] a sense of place and order. It’s crucial. I have a mixture of text work, painting, and performance. The two live performances are both different. It’s quite nice to do two different ones rather than the same one.

MCDERMOTT: Do you usually do the same performance repeatedly?

TOMPKINS: The most recent one is Like Saki, so there is some natural leaning toward wanting to do that one very often. The performances have a bit of a life and a time scale to themselves, but because it’s back-to-back in New York, I can’t do the same one. Very often they’re in different cities or different places, with different audiences, so I can. The way I perform or the setup is always same—just me and a microphone and the text—and they usually have some relation of how physical that stack becomes. When I’m editing it together, the density of the papers is an indicator to be like, “You need to stop.”

MCDERMOTT: I read that you just write everything down in the moment.

TOMPKINS: Yeah. I started using Notes [on my iPhone] but I do a lot of hand written notes. It’s a very slow, accumulative thing. Sometimes I think of phrases or questions or melodies, but they’re pretty complete and stay the same. When I go into the editing process, I re-look at the original intuitive thoughts and then it becomes the written performance or text work. Because they look quite big there’s this assumption that there isn’t much editing, but that’s a huge part of it.

I’m interested in really particular details, ideas, thoughts, and emotions, yet it’s defused with performance, where you can play with hiding things, or be more confrontational about something shielded. There is this process of layering in performance. For me, there’s the certain focus points that come out, which could reference a song or a pop disco, or something really abstract. It’s not totally fulfilling or complete, but rather an ongoing incompleteness. I’m really interested in the audience’s relationship with myself, and my relationship with them.

MCDERMOTT: Do you ever personally interact with your audience?

TOMPKINS: That happens a lot at the end of a performance. Recently I’ve thought about bands or performers who appear from nowhere: You come out of the greenroom in this secure little unit, then you do this thing and you’re shielded from everybody. I’m thinking of brilliant people, like Mariah Carey, who have no interaction. They interact with the audience at the time of the live thing but there’s no build up and there’s no afterward.

MCDERMOTT: Could this come from you being in a band and having the experience of not interacting?

TOMPKINS: Maybe. I think it’s that mix of the art scene and music scene. They’re really quite different, and I suppose my own work crosses over both. At an opening, you’re standing around, surrounded by art, you’re meant to be looking at it but you’re not—you’re socializing, you’re drinking, you’re doing whatever you want—so it feels quite fluid for me stand with a friend or stranger and then pull out of that crowd for a performance. Obviously something’s happened, I’m different off- and on-stage, but there is no “off- and on-stage.” It’s a common ground. Being on the same level as everybody is really important to me. I’m trying to do really basic stuff like communicate, convey, talk, see, and invite joining and intimacy. What I’m trying to do is attach. It’s not about being separate.

MCDERMOTT: Growing up were you interested in performance? Did you perform as a kid?

TOMPKINS: No. I’ve got a twin sister who’s an artist and growing up I was always “the loud one.” She’s not actually quiet at all, but I would rather fill a gap with chatter and she would just let a gap be. So there was no inclination to actually perform.

MCDERMOTT: So when did you start performing?

TOMPKINS: The first thing was private and when I was at art school. It actually came out of sheer, “Oh my god, I don’t know what I’m doing!” I was in the painting department and I wasn’t painting. I struggled with not knowing what to paint. So I used to go to the library and get a huge pile of books totally based on what appealed to me [aesthetically]—all art, art theory, and fashion. The library had these little study rooms and I used to go in with these books and a Dictaphone. It was a way of recalling experience. I don’t know how it became externalized, really, because it became an internal enjoyment. I would record intuitive comments about covers, pages, things I didn’t like, things I did like—just these snippets, edited things that I could expand and repeat. It was quite similar to the way the work is now.

MCDERMOTT: Do you remember your first performance?

TOMPKINS: Yeah, I remember I had accumulated six- or seven-hours worth of Dictaphone recordings. It wasn’t deliberate or intentional, but I just kept doing it. A couple of years later, after art school, I was in a group, a sort of collective of artists, who were friends from Glasgow. We used to put our processes together. My sister would make paintings, and the others would make installations. My contribution was sound recordings. Eventually it moved from recording this intimacy, me and the books, to a performance at Transmission Gallery. That was the first time I actually stood in front of an audience. I actually read sheets of paper and the only difference is that now they’re more fixed. There’s this start and finish, it has this book-y form, whereas early performances I walked around with my microphone and threw the sheets of paper away.

MCDERMOTT: I want to ask about the hanging text works. Usually you print on white paper, so why did you decide to use color for this show?

TOMPKINS: For years I’ve used that [white] paper. It’s so subtle. I really love color and I wanted to make something that isn’t very subtle. They’re done on a typewriter, so I might do one four times; it’s about the spacing. I’m more conscious when I know they’re going to be seen by someone else, whereas in the performance, it’s just me that sees it, so I’m much more casual about how it’s written. But on these [hanging] pieces it goes the other way. It’s very deliberate if something’s spelled wrong or if it’s really tightly spaced. I was actually thinking about abstract painting with these brackets of color. They have lots of different references and these references actually come from the performances I’m doing.

MCDERMOTT: And the title of this show comes from a performance, right?

TOMPKINS: Yeah, I like the way it sounds out loud. I was thinking about this abstract person who sounds like a man but could be replaced by anybody. “When Wayne Went Away” is about loss, or missing, gaps, separation. At the same time it could be about “dot, dot, dot,” what happens after, what does it suggest? There’s a lot of suggestion in my work. Not a lot of answers. [laughs] Just a lot of “dot dot dot.” I think of it as freedom.

MCDERMOTT: So let’s talk about the paintings, because I honestly didn’t even know you exhibited paintings.

TOMPKINS: I’ve really only been painting in the past three or four years. I could count the amount of paintings I’ve shown, and it might be about 10. They usually have words on them, but for this show there was a shift. I thought there’s going to be a lot of language with the performances, the text works, so looking at these paintings, they are actually quite blank. They’re much more about surface. I was thinking about color and mess, and then I wanted to put in words—one has an E—but there’s this wanting to put in, and actually taking out. These are much more empty. There’s texture and color and surface, but there’s not much content. Hopefully there will be some sort of relation between texture, surface, language, and what’s missing.

MCDERMOTT: What have you been reading or listening to recently that has really stuck in your head?

TOMPKINS: It’s really random. I’ve been reading this book, which I was attracted to by the title, by a Russian guy about TV and politics in Russia and Putin called Nothing is True, Anything is Possible[: the Surreal Heart of Russia]. It’s about corruption in Russia, how everything is available but it’s all mixed up. Then, The Modern Institute in Glasgow always gives us really great Christmas presents and they got me The Selected Poetry of Pier Paolo Passolini. I really like that, but again, it’s about [visual] attraction. One side of the page is in Italian and one side is in English. I like not understanding. I know bits of Italian, but I find it exciting to look at it and be like, “I don’t know what this is, but I like it.” Music, I have a very wide taste. I like actual songs and bands, but it’s usually parts, like the production, the bassline, the drums, that I’m really attracted to. I listen to it repetitively.

MCDERMOTT: Do you listen to music while you work? And do find that lyrics sometimes end up in your performances?

TOMPKINS: Sometimes I start with music on and then I get distracted because I’m working to a different rhythm; I’m not working to myself. So, I don’t have music on when I’m working. Once I sang part of The Beach Boys’ God Only Knows. I thought, “Most people know that phrase, even if they don’t like The Beach Boys.” You can play with that and sort of annoying people—there’s a real fine line between repetition being really exciting and offering up change, or being more drony and trancy and almost going nowhere. I ended up singing “God Only Knows,” slightly changing the words and going on a little bit too long. I suppose I’m interested in boundary. How long can you expect people to stand there?

MCDERMOTT: The National played one song for six hours at MoMA PS1 a few years ago.

TOMPKINS: I like that. You just go somewhere else in your head with that because it’s going on and on and on. My recent performances have been about 20, 25 minutes long, which seems quite a good length. I’m not really interested in making someone endure a performance or stand there for too long. I like to think about the length.

“WHEN WAYNE WENT AWAY” WILL BE ON VIEW AT LISA COOLEY IN NEW YORK THROUGH MARCH 27, 2016.