Ryan McGinley

In 2003, at the age of 26, Ryan McGinley had his first major solo show in New York—at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Today, after more than a decade of the art world strategizing and promoting young artists as instant masters worthy of career-size retrospectives with what is often still embryonic material, that fact may not ring as particularly astonishing. But I remember the opening night of that show in the uptown Breuer building, passing through the gallery alongside so many downtown friends-all of us still struggling with our art and lives and wallets in the city—and the strange swell of pride we felt that night for McGinley’s antic, over-the-edge photographs hanging in such an esteemed institution. It was an exhilarating, hopeful feeling that bordered on validation. One of us—through hard work, a refusal to bend to etiquette, and an ingenious eye for his own surroundings—had made it. It is difficult to imagine the careers of many of the artists who sprang from McGinley’s orbit—several of whom appeared in his early photographs, like Dan Colen and Dash Snow—without McGinley’s encouragement and success. You rarely get to pick the artistic pioneers and figureheads who come to represent your time or generation, but McGinley had captured—gorgeously, hypnotically, unflinchingly—the wonderful, doomed wilderness of New York and youth that we knew and believed in as our own.

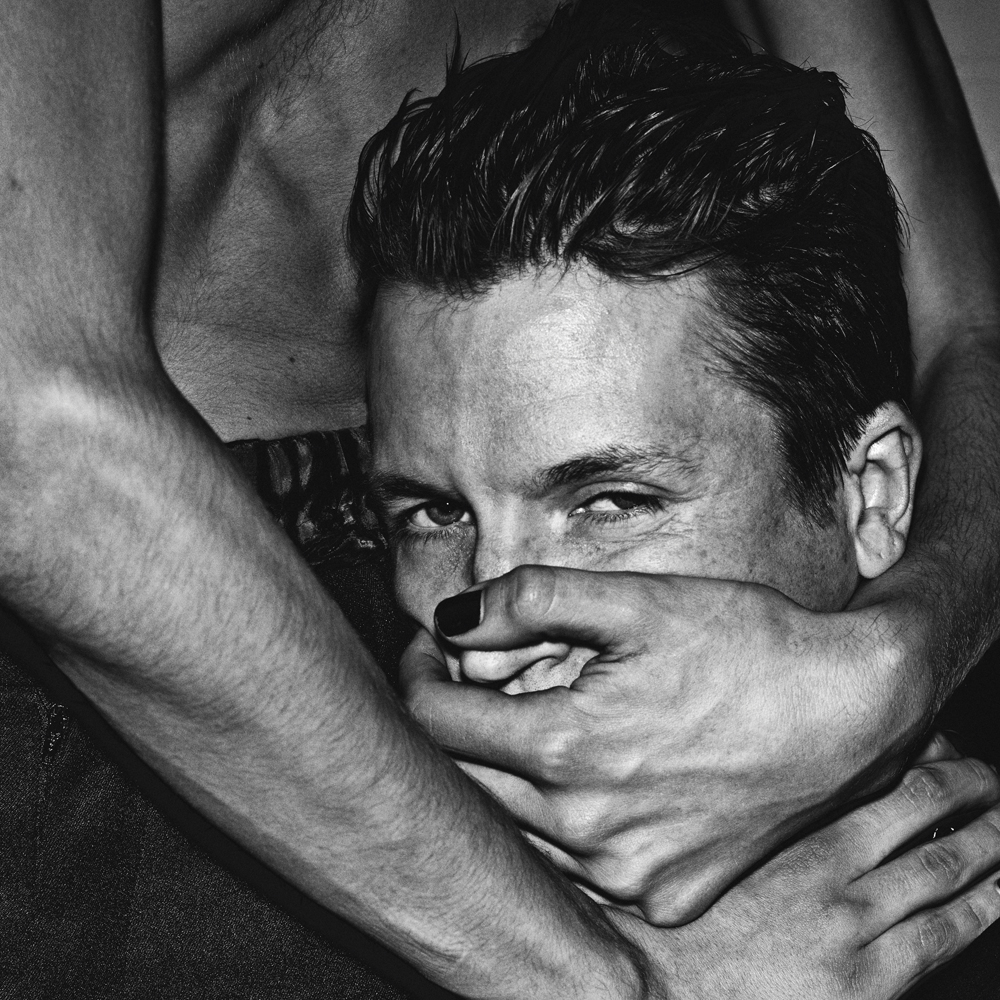

Of course, the photographic work of the New Jersey-born, New York-made artist had its historical antecedents; those range from Larry Clark to Nan Goldin, both of whom also brilliantly managed to create radical social tableaux with still images that seemed soaked in the madness and euphoria of their moments. But for us, it was McGinley’s prints that got to the heart and the heat of a giddy, semi-lost generation caught in the aftermath of the AIDS epidemic, in the era of 9/11, and in the increasingly policed, gentrifying urban sprawl that no longer safeguarded individual freedoms and dizzy misbehavior. Behavior is really the crux of much of McGinley’s output: How do we behave in the intimate spaces we create with friends and lovers, on rooftops or behind locked apartment doors, beyond the lens of judgmental eyes, in the safety of other oddballs and rogue performers like us? McGinley’s subjects, even when clothed, feel stripped, and because of this, they are at once beautiful, frightening, and honest. Today, we are highly attuned to the fact that cameras are all around us, constantly monitoring our behaviors and canned reactions; but for a time, it seems as if McGinley’s camera created a temporary, portable free zone in a post-Giuliani universe where personal conduct was allowed to run wild. McGinley offered a stage without any need for staging or rehearsal; the results could be perceived as anti-selfies in their celebration of more authentic selves. And if any viewer found the conduct portrayed in the work “perverse” or “disgusting”—vomit, cum, blood, drugs, blow jobs, bruises—it only indicated the social hygiene instilled in such a viewer’s prudish sense of humanity.

This February, the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver will open “Ryan McGINLEY: The Kids Were Alright,” an exhibition of McGinley’s early photographic archive, complete with some 1,500 Polaroids never before on view that the artist took in downtown Manhattan during his years in art school. A corresponding monograph is out simultaneously from Rizzoli. In these early images, we see an artist building his visual vocabulary and testing out the contours of his aesthetic and style. More than mere juvenilia, these images stand as a testament to McGinley’s ability to draw out his subjects’ personalities and turn the camera itself into an active participant in all manner of intimacy and play. (I can personally attest to McGinley’s appreciation of play; I distinctly remember being at the East Village bar the Cock in the early 2000s, when McGinley planted his Yashica T4 camera in my hand so I could take a photograph of him with the priapic, nude go-go dancer on the bar.) McGinley, now age 39, recorded a time in New York that no longer exists, but unlike many photographers, he did not let his first successful chapter define his career. Among other projects, he went on to create lyrical odes to travel and formal nude studies. Recently, his friend, the artist and filmmaker Mike Mills, met up with him in New York to talk about those young, uncertain years when he was finding himself as an artist and a man. -Christopher Bollen

RYAN McGINLEY: Where are you staying while you’re here?

MIKE MILLS: The Standard in the East Village. It’s like I open the windows and I’m looking at Cooper [Union].

McGINLEY: [laughs] A trip down memory lane. You went to Cooper, right?

MILLS: Yeah. I always kind of dissed it and never did any alumni stuff. The students were rad. The organization itself was like going to the Port Authority. There was no love.

McGINLEY: That’s the thing about Cooper; it has no structure. A lot of artists need structure.

MILLS: But there could be a little love, not just, “Fuck you.” But I was there starting in ’84. My first year, one kid shot another with a BB gun. And the reaction was, “Maybe you should go to a hospital … I think there’s one uptown.”

McGINLEY: Stuff like that still happens. This guy I used to photograph a lot got kicked out because he did a performance in class where he called his mom and told her he was committing suicide. And then he just walked out of class. I was like, “Wow.”

MILLS: We had some of that, too. There’s a fair amount of fighting among arty white boys. It’s a weird thing.

McGINLEY: Art school thugs!

MILLS: A lot of that’s coming out of pain and confusion, but not in a great way.

McGINLEY: Pretty much all of the work for this new book was made when I was at Parsons.

MILLS: When I was looking at it, I was tripping because I hadn’t seen many of your Polaroids before.

McGINLEY: I’ve never shown the Polaroids.

MILLS: That’s what I thought. And when I was looking at them, I was thinking, “This stuff is so friendcentric. And deeply intimate. What’s it like for you to look at these now? Because New York is such a different entity today than when I was running around Ludlow or wherever.

McGINLEY: Well, the cool thing for me about moving to New York was that I got to create a new family. I was growing up in the suburbs; I was one of eight kids. So I did have a community when I was younger, but all of my brothers and sisters were older. Basically, my mom had seven kids in seven years, and then she had me 11 years later. So when I was born, my oldest brother was 18. And my youngest brother was 11. By the time I was 7 or 8, everyone had moved out. I went from being with ten people all the time to being an only child. It really freaked me out. And then when I was a teenager and realizing I was gay, my brother was dying of AIDS. He came back home to live with my family. This was before AZT. He died—the worst. And since I wasn’t out to people, I was living this lie, you know? I couldn’t wait to come to New York to reinvent myself.

MILLS: To come out, too. You weren’t out to your family at this time?

McGINLEY: No.

MILLS: Not even your brother who was dying at home?

McGINLEY: Well, no. I thought that he, his boyfriend, and all of the gay guys he was around—who helped raise me—were all dying. At the time, I just associated being gay with having AIDS, because the only gay men I knew were all dying of AIDS. You just turned on the TV, and everyone was dying of AIDS. This was like ’92, ’93, ’94.

MILLS: When you say these adult gay men helped raise you, what do you mean? Like your brother’s scene?

McGINLEY: Yeah. When I was young, before he got sick, I would come into the city to visit him. He went to art school at SVA and did odd jobs. His boyfriend was a Barbra Streisand impersonator—as a full-time job.

MILLS: That’s a fun job.

McGINLEY: I remember before his boyfriend would perform, my brother would sometimes do a number as the Wicked Witch of the West.

MILLS: Did your brother turn you on to all the things that were going on in the gay community?

McGINLEY: Yeah, he turned me on to art. Because I was pretty Irish Catholic Jersey, the middle of the line. We grew up in a pretty upper-middle-class neighborhood, but when there are eight kids, we were told we were near poverty. Taco Thursday nights and fish on Friday because we were Catholic. There was no luxury. I never got on an airplane until I was 18. We drove everywhere. My dad was like, “Waste not, want not.”

MILLS: What did your dad do?

McGINLEY: He was a traveling salesman for Owens Corning fiberglass.

MILLS: My mom was a traveling saleswoman, among other things. And my sisters are ten and seven years older than me. So I know what you mean. But to be the eighth kid, that’s old-world shit. [laughs]

McGINLEY: I know. I think about it a lot now. My dad was in the Korean War. He got shot seven times. He had seven bullet holes in him. And out of his troop of 35 guys, he was one of nine guys that came back. And when he came back from that he had seven kids in seven years.

MILLS: One for each bullet hole! Was your brother out to your parents before he got sick?

McGINLEY: No. I mean, he was so flamboyant that it was just obvious. And the day that he graduated from high school, he moved to New York City. It was the same way with me. I knew my ticket out of the suburbs was art school, so I worked really hard to develop my portfolio and get a scholarship. Parsons gave me a full ride, so I was like, “Okay, I’m making it to the city.”

MILLS: You needed that. If you didn’t have the full ride, you couldn’t have done it.

McGINLEY: No. Because art school is so fucking expensive. [laughs]

MILLS: I was such a fuckup. I wanted to be a professional skateboarder, and I was very far from being that. I wanted to make it with my punk band, and I was very far from that. I just didn’t respond to school. And then all of a sudden, I was like, “Skateboarding and the punk band didn’t work out, what am I gonna do?” I was like, “I can draw!” I just started drawing my brains out. And that was the plan—or the third plan, really—to get me out of Santa Barbara. But I think I had a much easier time. I can’t imagine being gay went down well with Irish Roman Catholic, New Jersey vibes.

McGINLEY: It was never really discussed. Like, even to this day, my mom will ask me about my boyfriend and say “your friend.” And I’ll say, “You’re disrespecting me. He’s not my friend; he’s my boyfriend. He’s much more than a friend. You have to stop calling him my friend.”

MILLS: To this day. Wow.

McGINLEY: And she’s like, “I’m sorry.” But that’s how it went down then. Like, if my brother ever brought anybody home, it was his “friend.” Whereas all my other brothers and sisters, if they brought somebody home, it was their boyfriend or girlfriend, and it was taken more seriously. I should preface this by saying that I was never raised with anybody telling me that gay was bad. I was never told, “Fags are going to hell.” You just didn’t talk about it.

MILLS: How old were you when you started visiting your brother in the city?

McGINLEY: 5 or 6. This was in the ’80s.

MILLS: So we crossed paths. [laughs] Do you think anyone sensed that you were gay when you were a kid?

McGINLEY: No! Nobody. But when I told my mom, she said, “I knew.” And I said, “How did you know? When?” And she said, “I knew when you were in high school, and bottled water had just come out. You came up to me with a bottle of Evian, and you said, ‘Mom, bottled water is the best! I love it so much.’ I knew you were gay at that moment.”

MILLS: [both laugh] That’s hysterical. Bottled water was your tell. I should be super-gay by those standards. What art did your brother turn you on to before you went to Parsons? What were you looking at?

McGINLEY: He definitely turned me on to Keith Haring. He was a fan of what people were making downtown—Basquiat, Warhol. And then there were the heavy hitters I was looking at, too—Pollock, Rothko, Picasso. And through my family, I was turned on to all of the religious painters. My dad sort of fancied himself a painter at one point. And we had these pictures at our house that he painted, like Bob Ross-style pictures of dogs running through the forest. Everyone was always like, “Your father is very artistic.”

MILLS: Did he support that artistic side of you?

McGINLEY: They were supportive. And from a young age, I was always the kid that won the supermarket contest for a Smokey Bear drawing. I was voted most artistic in school. Stuff like that.

MILLS: I did the yearbook. And when I graduated from junior high, people would line up for me to do band logos. I could draw the PiL logo perfectly.

McGINLEY: In high school, my art teacher really helped me develop. We got super-close. And she took me under her wing because my brother was dying then. I almost had to repeat a year because I was at home with him most of the time, kind of nursing him and making sure he didn’t kill himself. She just let me be in the art room a lot.

MILLS: That was an intense time for you, not just dealing with growing up, but being there for your brother.

McGINLEY: Yeah. We used to have to put a chair in front of his door so he wouldn’t leave his room at night to go upstairs to grab a knife to stab himself. Because he tried that. I remember one time I was working at the public pool: I came home and he’d drunk, like, five bottles of wine and had taken all of his medicine at once. It was so weird. I couldn’t touch him because I didn’t know if the wine was blood. I called an ambulance, and they pumped his stomach. It was rough, dude.

MILLS: That kind of experience makes me see how you’ve become so totally out in every way emotionally. Your photos represent that. They have this kind of openness. You include yourself. You don’t hide behind the camera like some photographers do. And that’s really vivid in your work. Your love and interest in people is really front and center. There are other photographers who’ve taken pictures of subcultures, but that work is much colder and sometimes almost meaner to the subjects. I never get that vibe from your photos at all. Sometimes you are having sex with your subjects, but even when you’re not, you kind of are. You’re really involved.

McGINLEY: Yeah, there’s a heavy intimacy.

MILLS: Do you think your openness and willingness to talk about everything and being willing to share it and that sort of desire for intimacy has anything to do with the time you spent with your brother?

McGINLEY: Yeah, totally. Because it was such a secret in the suburbs. When I had to wheel him around in a wheelchair through the neighborhood, we weren’t allowed to tell anybody he had AIDS. We told everybody he had cancer because we were worried that people would egg our house or something; that people would retaliate against us. So I think from that secrecy and from my own personal emotions of knowing I was gay, I was holding in these two giant secrets, holding them in so hard, that when I came to New York and found my scene—which is all the people in the new book—I was able to unleash all of that secrecy. Discovering all of these really awesome people was just the best. And that spiraled into being like, “I’m not going to hide behind anything. I’m going to put every aspect of myself out into the world and try to convey it through photography.” Actually, I didn’t study photography at first. I went to school for painting my first year, poetry my second year, graphic design my third and fourth year, and photography my fifth.

MILLS: So it was at the end of all those years at Parsons that you shifted?

McGINLEY: Yeah. When I first started at Parsons I was really into graffiti and skateboarding. The first year was transitioning out of that and realizing I had to dedicate my life to something else. I kind of had to put down the skateboard. From 8 to 19, I was skateboarding every single day. That was my life. I worked at a skate shop. I watched skate videos. Then I realized, “Okay, I got to tone this down and take this art thing seriously.” I think the driving force when I moved to New York was the fear of going home with my tail between my legs. Because a lot of people, even my parents, thought, “Art school, I don’t know. We’ll support you but the success rate for artists is really slim.”

MILLS: I got that talk, too.

McGINLEY: I think I was just fucking scared. I put all of my time into art because I couldn’t go back to Jersey and work at Starbucks. Now I look at these photos from that time, and there’s so much energy in them and so much adventure. It was so good for me, because I met a lot of people when I moved to New York who were gay and my age, and they were alive and thriving. That was the first time I really had a peer group. I sort of had an identity crisis when I first came out. I didn’t have a community of artistic people I identified with because I was coming out of skating and graffiti, which is really—

MILLS: Homophobic.

McGINLEY: Yeah. Or just hetero.

MILLS: Not the graffiti scene as much, but the skating scene is straight-up homophobic I would say.

McGINLEY: I guess you’re right. So finally I met Earsnot. I knew him from skating in high school, and I would always seem him at Astor Place. Then someone said to me right when I came out, “Earsnot’s gay.” I literally couldn’t believe it, because he was so tough. So I went out looking for him and hunted around for a few days, and I finally caught him at Astor Place. I was so scared to ask him, but I just went up to him. He was like, “What’s up, Ryan?” And I was just like, “Um, are you gay?” He’s like, “Yeah, man. I am.” It was like a religious moment, like I had found somebody who skated, who did graffiti, who was into Wu-Tang Clan, into the same stuff that I was into …

MILLS: And it sounds like he didn’t have any shame about it.

McGINLEY: No. I mean, he had his own life. He was homeless at the time. He had run away from home. He boosted. He stole for a living. He was living on the street, sleeping on the subway, stuff like that. He had his graffiti crew called Irak. That was Earsnot’s and Dash’s crew. That’s how I met Dash Snow. And from there, I met all these people. That’s when I really started to feel good about myself and feel like I had friends I could be honest with and that were into the same things I was into. I didn’t have to be friends with people who were into pop music. [both laugh] I’m trying to think who the pop stars of that time were—Britney Spears? I just didn’t identify with that.

MILLS: I was never in any graffiti scene, but people I know who are in it tell me it can be very exclusive—or at least not very inviting. Like, “You’re not legit.” What was that scene like? From the outside looking in, it seems like you guys were all so nice to each other.

McGINLEY: I saw Earsnot fight a lot of people on the street. That was his thing. People would be like, “Yo, you’re a faggot.” And he was so big and strong that he’d fight everybody, and he would always win. Then he would say, “You got your ass kicked by a faggot. Go fuck yourself.”

MILLS: How did they know he was gay?

McGINLEY: Because he was out. It was just word on the street. People just knew. And I think the Irak crew were the most up around the city at that time, so graffiti people were like, “Who the fuck are these kids who are just tagging everything every single night?” They really became super well-known in the graffiti world. And that was at the time that I started taking photos and publishing them in magazines and books. And it sort of grew into a legend. There were stories in Dazed & Confused and Vice about this crew with the gay leader. Their shenanigans and adventures got sort of mythologized, maybe through these photos.

MILLS: How did the Polaroids happen? Because that happened before you started shooting Irak.

McGINLEY: My Polaroids came out of graphic design. When I was in high school, I used to make these silkscreens with this little Japanese machine that I bought at Pearl Paint called Print Gocco. You make this silkscreen at home with it. Then in college, all my friends were graffiti writers, but I never wrote graffiti. I wanted to participate and do something cool on the street, so I’d make these portraits of people. I’d isolate them on a white wall, make a silkscreen of it, and do these portraits in bathrooms and all around. That’s how I started the Polaroids. I photographed a bunch of my friends against a white wall, so I could have a clean background for the silkscreens. I did maybe the first 20 or 30 for these silkscreens. And then the silkscreens kind of died out because I didn’t have much of a life in crime as a graffiti writer. But that’s how I got into photography.

MILLS: Do you remember your first camera?

McGINLEY: I remember in Big Brother magazine, there was an article that Earl Parker wrote about the Yashica T4. It was like, “The T4 is the best camera. Send me some money so I can get a new one.” That magazine was my Bible at the time, so I got a Yashica T4. And that’s what all these photos are shot on.

MILLS: I still have mine in my garage.

McGINLEY: It is such a beautiful camera.

MILLS: I looked through the essays in the book, and what I found impressive is how obsessive everyone says you were about taking pictures. How you’d just wake up and start shooting, how frequent it was and how you made it safe for everyone. You just did it all the time and really integrated it into your own life and the life of your friends. The consistency was part of the success.

McGINLEY: Most of these photos are pretty documentary. I’m a fly on the wall. They’re just what was happening around me at the time. I never really set too much up back then. But I did need some sort of structure at first in order to be able to shoot my friends, just to have some control in saying, like, “Okay, every time you come over to my apartment, I’m gonna take your photo.” And it was that thing of “Stand up against the white wall.” That sort of opened the door to be able to take all the rest of the photos, if that makes sense.

MILLS: Yeah, I know what you mean.

McGINLEY: I was scared to do set-up shoots with people because that felt too real to me—like, I don’t think I really owned being a photographer at the time. If you asked me then if I was a photographer, I would probably say, “No, I’m a painter or a poet,” because that’s what I was studying at school. But somehow the repetitiveness of shooting those Polaroids was one foot into being more professional about it.

MILLS: I can totally see how the Polaroids opens the door, like, you come in the door, you get a Polaroid. Were you shooting every day?

McGINLEY: From ’99 to ’03, basically until my first show at the Whitney, I was out every single night, and I would shoot, like, ten rolls a night. And the Yashica was so perfect because it was so small, it would just go in my pocket. I didn’t have to be the photographer with the camera around his neck. I would throw a few rolls in my socks and go out and just shoot. When I was in art school, the photo kids were separated from the rest. If you did sculpture or painting or graphic design, you were all taking the same classes, but the photographers just went straight into photography. I had some friends who were in photography. And I was always like, “Whoa, what’s up with that?” The thing that really got me was, one day, my friend took a photo of me, and it ended up in zingmagazine. I was like, “What the fuck? She just took that photo, and now I’m in a magazine. This is crazy.” Then she blew it up, made a poster-size print of it, and hung it up at Parsons. And I was like, “You can make posters?” Growing up, my room was covered in posters. I was like, “I want to make posters.” So I asked her to show me how. That was the thing that really got me. I was studying graphic design at the time, when negative scanners and all that stuff was coming out, and you could do it all in your apartment. So I would shoot, make contact sheets, scan all the cool negatives, and make all these zines and books of my photos to give to my friends. I was really into zine- and bookmaking from skate culture.

MILLS: I remember I was out with Andre [Razo] and Athena [Currey] at some bar on Second Avenue, and you came up to me with a book you made.

McGINLEY: That was my handmade book. That would have been around 2001. I hope you still got it. That’s a good one.

MILLS: I do. We didn’t know each other, and you came up to me. You were very sweet, you said something nice about my work, and you were so frickin’ enthusiastic in a totally charming way. I was like, “Who is this person?” And then I loved the photos immediately. I would never have the bravery to do that. Like, my punk rock vibes, you can’t do that for some reason. I was truly impressed, and it just suited your soul so perfectly. It was just honestly you. And it goes hand-in-hand with your photos.

McGINLEY: I was definitely ambitious about giving the book out. And I knew you were part of Alleged Gallery. Alleged was my church. In, like, ’95, I was skating at the Brooklyn Banks, and Mark Gonzales was there, and we were like, “Holy shit, it’s the fucking Gonz.” And then he was like, “Oh, dudes. Come with me! I’m going to look at some paintings!” He brought me to Ludlow Street. And I think it was the David Aron show actually. I was like, “Oh my God, skaters are artists.” Before that, I hadn’t made the connection between skaters and artists. Artists were in MoMA. Then I realized my best friend’s sister was an intern there. She would sweep the gallery. That was sort of my in. When I moved to the city, I would attend every Alleged opening. I started to learn about everyone who showed there—you, Barry, Ari, Harmony, Terry, Simone Shubuck, Susan Cianciolo. I saw that show you did, “Hair Shoes Love and Honesty” [1998]. I was like, “I don’t know what I’m watching or what these people are talking about, but I really like this.” So I started to look you up. You were designing for all the bands I was listening to. And I was really into X-Large and used to wear all of the clothing and go to the shop on Avenue A. I made the connection that you were that dude. So when I got some work together and made that book, I really wanted the people I admired to see it.

MILLS: I have a 4-year-old son, and I hope he’s like that. Because it’s just so right on.

McGINLEY: The cool part about New York is that you can do that. You can talk to all the people you admire.

MILLS: The punk scene I grew up with was somewhat snobby about ambition. You always had to shit on yourself. That was the m.o. It’s not really healthy. But so much has changed. Now when I’m in New York, it’s such a trip. Do these photos feel ancient like that to you?

McGINLEY: When this project came along and the museum in Denver asked me to do a show of my early work, it really forced me to go back and edit all the Polaroids down and dig into my archives and look for stuff. And there was a lot of stuff that I was scared to put out there. I was going through a tough time when I took them. We were all drinking and doing drugs, and it was very intense. And now, looking back, a lot of people died. A lot of my close friends have committed suicide or died of heroin overdoses. I guess coming out of that time where I was making work that was not thought out at all; it was just raw and was about what was going down.

MILLS: From my high school punk scene, so many people died. A surprising amount. I look back and think, “Oh, that was a time of wildness that helped us find ourselves.” But we weren’t as sophisticated as you guys in terms of drugs and stuff. Our drugs were pretty normal. Some people went all the way, and somehow in Santa Barbara in the early ’80s, they found crack and didn’t come back. When I look at all the wildness and feralness in these early photos, in a way, it’s beautiful—you all are just fucking beautiful. But there’s got to be that other side for you, too.

McGINLEY: Just being friends with people now for over 15 years, you realize what we all came out of. What we came out of was the intense feeling of growing up. It sounds kind of cliché, but it’s true. Every single person in these photos came out of some kind of an intense home experience. And what I really believe is that there are no coincidences anymore. That me and all of my friends in these photos are magnets to each other. You find the people that you need to find. There’s this gravitational pull. Whatever emotions you’re going through, you somehow seek out the people that are going through similar emotions or that maybe have something you need. But I also look back, and I think, “Holy shit, I was a fucking madman.”

MILLS: Totally.

McGINLEY: I spent all of my money on film. I remember I would do these set-design jobs or transcribe or just anything to get, like, a $100 check and go immediately to Adorama and buy expired film. I remember using my brother’s credit card at CVS all the time. He was like, “Why are you sick all the time?” Because I was buying Polaroid film. And I was like, “I just really needed a lot of medicine.” [Mills laughs] Right now I’m really trying to identify my obsessive behavior and to calm it down. Because this book has over 1,000 Polaroids, and that’s a really tight edit. I’ve shot thousands and thousands of Polaroids over the years.

MILLS: The book really gives that feeling of obsession.

McGINLEY: The thing about being a photographer that’s so cool is that you get to participate, but you also get to disappear. The camera is in front of your face all the time.

MILLS: As a normal person, I can be kind of shy and awkward. But when I’m directing, when I have a job, I’m like a super-lovey Italian person who will just come hug you all the time. I change a bit.

McGINLEY: A camera gives you a purpose. I also think a lot about control nowadays, and I really want to let go and just be more in the moment. The camera gives you some control. In a lot of ways I look at these old photos, and I don’t know if I would have been able to communicate with these people on this level if I didn’t have a camera. I think I would still be so shy. When I moved to New York, I was still in the closet. And when I got my first apartment, after the dorms, I moved in with this dominatrix. We developed a relationship, and one night, she said, “Let’s fuck.” I was like, “Uh … I don’t know, maybe not tonight.” And she was like, “Ryan, every guy in New York wants to fuck me.” [Mills laughs] She was like, “What’s wrong?” And I was like, “I don’t know.” And she was like, “You’re gay, aren’t you?” And I was like, “Maybe.” I called her recently and thanked her. We hadn’t spoken in years. I said, “Thank you so much for helping me. Because if it wasn’t for that, it probably would have taken me another two or three years to hook up with a guy.” She forced me to do it. She said, “We’re going out, you’re going to point to guys you think you’re into, and I’m going to sort it out.” In true dominatrix style.

MILLS: You’ve got to make this movie. First half is you and your brother, the second half is that. It’s fucking insane. But those stories are so beautiful. That she was giving you access to a braver, weirder world.

McGINLEY: She was just so nonjudgmental. That’s really the people I was looking for, and those are still the people I’m looking for.

MILLS: You mentioned that there were a lot of people in these pictures that have since passed away. Does it make you sad to see them?

McGINLEY: The person I think about most is Dash Snow. Because he was really into being photographed by me, and we had this relationship that was like artist and muse. It was awesome to find somebody who was so open and excited to having me document their life. I feel like my boyfriend at the time was always annoyed by my camera. He was always like, “Oh my God, put the camera away. Do we have to shoot every time anything happens?” But Dash was down. And since he was a graffiti writer, he was out every single night bombing. So I just followed him and his life, and we developed this super-close relationship. I think about him a lot, and now just really looking at all these photos of him as a young guy … I don’t know. I think about if he was still alive, what he would be doing. I see his daughter, and I look at her, and I can see him in her. I think about how much he influenced me. We really influenced each other. But he has his own style of photography. You can see just how different his world was in his Polaroids than my world. His was so much about darkness and despair. But in other ways, our work is similar. It’s like two different views of a scene. There are several of my early boyfriend in those photos. I just remember how excited I was to have a boyfriend and be in love and to document it. There’s a lot of love in those photos.

MILLS: That’s your thing. Often what’s going on is really rough, but it’s so sweet, too. Really, there is so much love coming from the camera.

McGINLEY: This book goes up until 2003 when I had my exhibition at the Whitney. That’s right about the time that my friends stopped being models for me. Partly that was because people started to get their own lives. This was some sort of Peter Pan art school period, where we really didn’t have any responsibilities. And it didn’t matter if you were poor or wealthy. None of that stuff comes into play until later. We were all really just operating on the same level. But then people started to become artists or musicians or gallerists. Like Dan [Colen] became a painter. And that’s when I started to hire people to be models. Because right after that Whitney show, I was like, “What am I going to do? I can’t just continue to be downtown shooting out and about at night.” I was trying to stop drinking and doing drugs. And I just needed to figure something out.

MILLS: That’s brave that you just tried to do something different than the thing that you were so rewarded for.

McGINLEY: It was hard, but there wasn’t any alternative. People knew who I was in New York. And it was also the rise of the internet and blogs. Everyone started to have a camera. That’s when I started to travel outside of New York and go into nature.

MIKE MILLS IS LOS ANGELES-BASED FILM AND MUSIC DIRECTOR. HIS NEW FILM, 20TH CENTURY WOMEN, WILL BE RELEASED AT THE END OF THE MONTH.