Word on the Street: Robert Montgomery

London-based, Scottish artist Robert Montgomery occupies a delicate space between street art and academia. Educated in the Situationism and Marxism, he took these texts at their word, and brought his slyly political, text-based art to the public sphere. His simple, graphic poems have since been plastered, often illegally, over advertisements and billboards internationally. Tomorrow, Montgomery will invade a new commercial space, the Dior Homme Pop-Up shop in Soho, with a 2009 piece, WHENEVER YOU SEE THE SUN REFLECTED IN THE WINDOW OF A BUILDING IT IS AN ANGEL, which was selected by Dior’s menswear designer Kris Van Assche.

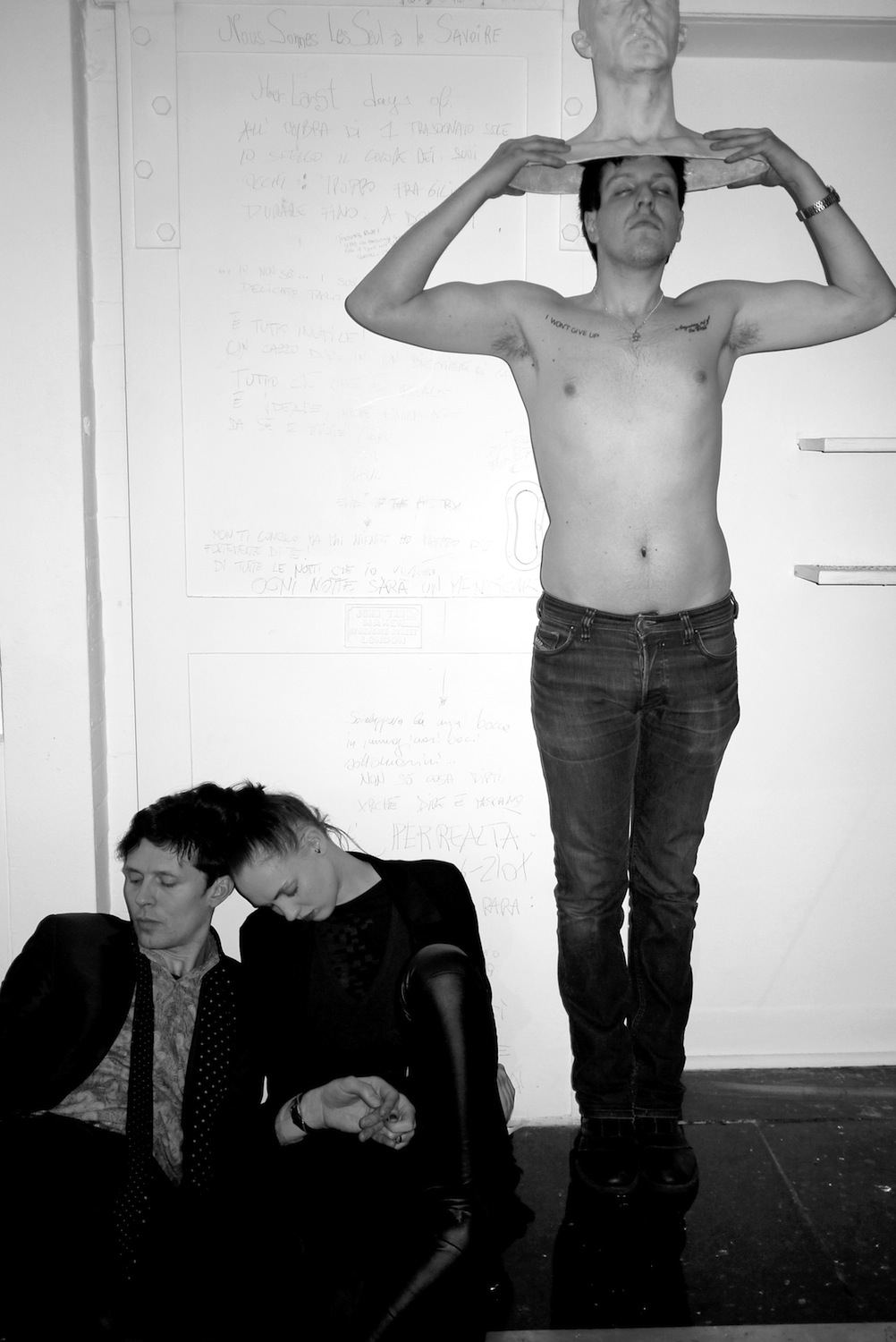

We recently caught up with the artist to discuss the work, his relationship with the understated, quietly rebellious Belgian designer, and the time his girlfriend discovered a 22-year-old woman with Montgomery’s art tattooed on her arm.

ASHLEY SIMPSON: Can you tell us a little bit about your background and how you got involved in the Situationist tradition?

ROBERT MONTGOMERY: I grew up in the central belt of Scotland in the 1980s, my grandparents were miners and my father was a bank manager, and my parents (and my grandparents) believed fiercely in education, by which I mean I was lucky. I became interested in text-based art in the library of Edinburgh College of Art where I went to study, and I discovered the Situationist tradition because I loved Roland Barthes and Jean Baudrillard’s books. They are both good writers, they are very funny sometimes, and they keep aesthetics connected to real life and to politics. Next in that canon you have to read Deleuze and Guattari. Then I found Guy Debord, who writes beautifully and has higher ambitions. And then I started to do my own poems on the sides of buses and on walls with spray paint. Obviously my own work comes from a conceptual art tradition, but I love the graffiti artists, and I feel spiritually closer to them than to most contemporary art; they make the city a free space of diverse voices and we shouldn’t get all cynical about them just because Banksy made some money. I collaborate sometimes with Krae, who is an old school east London graffiti writer.

SIMPSON: We’d love to hear about the piece for the Dior Homme shop. When did you originally create it?

MONTGOMERY: It’s a really simple piece actually, it just says, “WHENEVER YOU SEE THE SUN REFLECTED IN THE WINDOW OF A BUILDING IT IS AN ANGEL,” and it’s made of 12-volt LED lights that you can run off solar power. It is about trying to find a sense of the sacred in the everyday, a sense of God in the mundane. It seems to me it would be good for us to do that right now

SIMPSON: How do you think the commercial—and specifically high fashion—context affects the way the work is viewed and interpreted? Can you tell me about your relationship to Kris and the fashion world?

MONTGOMERY: I don’t know Kris personally yet, but I feel a close connection because both of us are working with Barbara. Barbara Polla for me is one of the great, and too unsung, heroic figures of contemporary art in Europe in the last 20 years. If you look back at what she’s done with Galerie Analix-Forever in Geneva, she’s given so many first shows to artists who other gallerists don’t understand for another five years—Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Mat Collishaw, Vanessa Beecroft, Miltos Manetas, Martin Creed were all shown by Barbara at the very beginning. Martin Creed told me Barbara gave him his first real solo show outside of his small circle in London and that that show gave him a really important sense of confidence because it was somewhere else and he knew she was showing him just for the sake of the work, and not for any other agenda. Barbara shows my work because she loves it, she loves the poetry and the fact that I work in the public space, and I believe these are her same links to Kris: she loves his poetry too, and he also works in the public space, although in a different way than I do—he does it as a designer. I will know more this weekend when I finally meet him!

I’m not avoiding your question on my relationship to the fashion world or my work being shown in a fashion setting. My work’s most often seen in the streets on billboards. I don’t know if it being seen in a shop is any much different. Anyway I think Kris’s thing, his aesthetic and his positions, and Dior Homme as a whole is kind of an unexpected countercultural project within the massive machine of global brand high fashion, redefining ideas of masculinity.

SIMPSON: Is there a setting that you feel is most impactful? A public place that you would really like to exhibit your work that you haven’t?

MONTGOMERY: The street is the most impactful for me really, always, and the Internet. I guess I’d like to sell some more light pieces so I can rent some more billboards; that’s my only ambition in life really. Then I’d like to save up some money so I can buy a very simple wooden house, and then after that I’d like to start buying billboards. I’d like to buy a bunch of billboards in different cities so we owned them and I could give them to Occupy to tell the truth with.

SIMPSON: What’s the strangest or most surprising space you’ve shown your work?

MONTGOMERY: Tattooed on the arm of a 22-year-old hairdresser from Culver City I think. Lucy, who’s my girlfriend and makes my work with me, follows how the poems I write get posted by people on Twitter and from a Thursday to a Sunday on a Twitter trail she showed me THE PEOPLE YOU LOVE BECOME GHOSTS INSIDE OF YOU AND LIKE THIS YOU KEEP THEM ALIVE travels out into various communities of people, communities way beyond the contemporary art audience, and by the Sunday night a girl in California gets it tattooed on her arm and then posts that back on Twitter.

SIMPSON: A lot of your pieces, including the one shown here, include religious references. Can you talk about this?

MONTGOMERY: [laughs] Yep, I am really interested in who owns ideas of religion. What if I say I’m a libertarian, socialist, Occupy-supporting, anti-war, Christian? Is that a controversial idea? I don’t see anything really in the original semiotics of Christianity, in the specific parable of the radical socialist Jew from Galilee who becomes the hero figure in the Homeric-word-of-mouth-gossip-novel that becomes the Bible that should make that a paradox. What if I say that in my view about the least Christian thing you could do is what the Republican party are trying to doing again now, which is try to take charge of the richest country in the world and then deny the people of that country free access to free healthcare and free education and start more wars. Free healthcare and free and equal education and peace are about the only things I passionately believe in, and I think if you don’t believe in those but you go to church on Sunday then that’s hypocrisy.

SIMPSON: What are you working on now? Any summer plans or upcoming projects?

MONTGOMERY: I’m making some billboards for the garden of Tempelhof Airport in Berlin. I’m having some trouble writing them though because the site is so historically charged—it was the Nazis’ airport, and when the Red Army liberated Berlin, they drowned the last of the Nazi command in the basement. Then it was the US Air Force base during the Cold War. I’m trying to write about it so I don’t either ignore the histories of the place or be over-simplistic about it. Berlin seems like a place of healing to me though: you have both the Holocaust Memorial and Hiroshima Strasse side-by-side there. You have the whole last century libraried and you can see exactly what we did. Now there’s lots of artists and musicians moving there because they can’t afford the rent in London and New York, and they’re having children and making it a gentle place. It seems to be a place of hope now. The project is curated by Manuel Wischnewski from Neue Berliner Raume; it opens July 6, and the next day is my birthday.