Mike Mills

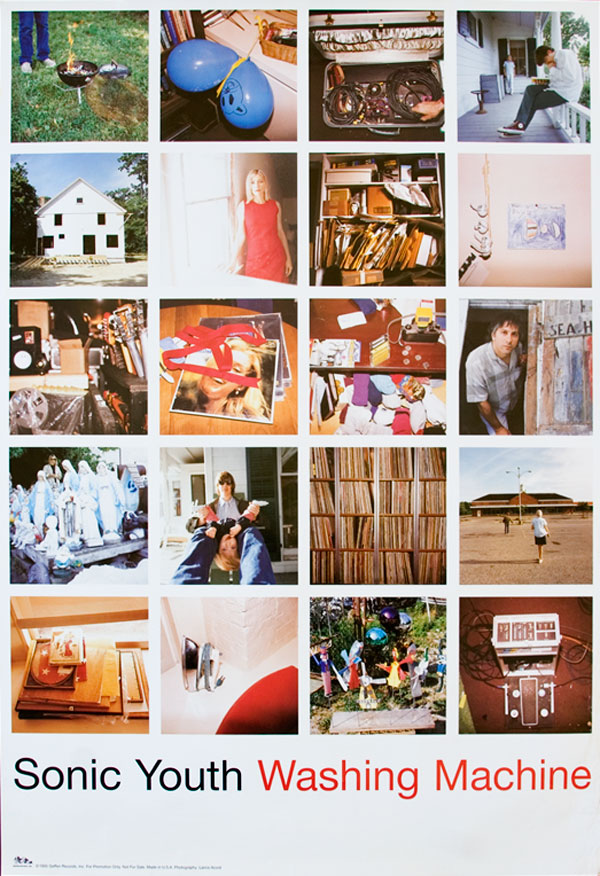

Mike Mills is a California-based artist, graphic designer, and filmmakerâ??a Renaissance Man if there ever were one, although he’s less interested in mastering different fields than he is in putting them all to his various purposes. Graphic design is generally considered secondary to the material it packages, but for Mills, the album art he’s done for Pulp, Battles, Sonic Youth or Blonde Redhead and his lookbook photographs for designer Susan Cianciolo stand alongside his feature-length films as part of an ongoing biographical project. His new book, Graphics Films, collects all formats in one place. It’s published with Damiani and Alleged Pressâ??naturally, as Mills is a longtime participant in Alleged Gallery, the legendary Downtown New York space run by Aaron Rose and Brendan Fowler from 1992-2002. Rose and Fowler still collaborate on ANPQuarterly, which has not infrequently featured Mills. Brendan is a jack of his own trades, as publisher, gallerist, performer, and an artist: He’s coming to New York the New Museum’s generational survey next month.

This isn’t Mills and Fowler’s first interview, but that doesn’t make reflection any easier. Mills says of his earlier work, “You’re always trying to wear the cool clothes and looking back you realize you didn’t even have your clothes on. No wonder everyone was giving me weird looks!” Upon the publication of Mills’ new book, Mills and Fowler are reunited by telephone. (LEFT: MIKE MILLS AND ELMO)

BRENDAN FOWLER: This is the second time I’ve interviewed you?

MIKE MILLS: Tilda [Swinton] used to use our dialogue to practice her American accent, because we had such weird Cali talkâ??it was totally “Like, dude, and totally.”

BF:Â It was also five hours long and like a therapy sectionâ??

MM: That was the one in the hotel.

BF:Â So this is the third time! What was the second time?

MM: It was before Thumbsuckerâ??was it for Interview? No, it wasn’t, but I can’t remember what it was. It was a little piece in the front of some magazine, some article about living in LA, you know, asking, “How can you possibly live in LA?”

BF: We did this five-hour interview for my book, which I was going to do with Alife. And then Alife was sued. The whole thing got put on ice. But that was the ice breaker. That’s how I got the whole back-story contextualized. So to that end, today we’re talking about the book. One of the great successes of the book is that it isn’t arranged topic by topic or genre or medium. It’s totally broken up.

MM: I was stuck with this quandary of, “How the fuck do I organize all this different work?” And it’s a fair amount of work.

BF: How many years of work is it?

MM: More than I want to admit. More than 10. It’s from the midâ??90s to now. So ten years, a very long ten years. That’s two years in vampire life terms.

BF:Â Almost two-and-a-half in vampire life terms. Let’s be honest.

MM: I said to myself, “I have to make this make sense to people, but this isn’t how my life makes sense.” These artist monograph style-books are usually chronological or they’re broken up into chapters by different mediums. I wasn’t very excited about that, but I was marching forward in the direction of a normal monograph.

BF: Those traditional categories didn’t make sense with your working practice. (LEFT: ED TEMPLETON IN DEFORMER, 2000)

MM: Sometimes you start a project and you think, “Oh, I just have to fit into a machine.” But I talked to Colleen Corcoran, a designer who worked with me on the book. She said, “You never present your work that way, when you talk at Cal-Arts or when you talk anywhere, you always say that’s the same issues and themes that come out in different stuff, so why don’t we organize the book that way.” It was really nice to have her eyes look at it from a distance and she made a stab at organizing things thematically. And I was like thank God, that’s such a relief. That is really how things work in my brain.

BF:Â For sure. Â

MM: People always ask me how I make sense of working in all different mediums or categories, how works? For me, really it’s the same issues that have been rubbing against my sensitive parts for years. [LAUGHS] Over and over again, I’m trying to express or communicate these big and small struggles to the world, and really to myself. Being a good Hans Haacke student, part of his influence on me is that there’s no difference between a gallery show and a film-or even an ad and a T-shirt-in terms of cultural legitimacy. They’re just different contexts in which to have some sort of communication. So hopefully the book presents it that way.

Â

BF: I’m glad to hear you say that it’s hard to describe too. I feel like we’ve been friends for so long and I’ll always hear that. “Oh Michael Mills, he’s the graphic designer guy” or “Oh, he’s the filmmaker.” Like whoa he does all this other stuff too.

MM: I’ve had one previous girlfriend, who, before we went out someone was like “Oh Mike Millsâ??this or that.” And she was like, “That guy, he just has it so easy. He just thinks he can drop in and do this or that.”

BF: But if you really had it easy, you wouldn’t be doing all that stuff.

MM: I would just be doing one thing and my life would be so much easier. But it’s not really the way I live. But I do think that it all comes from watching TV.

BF: Ok.

MM: When you’re a kid and Scooby Doo is your favorite thing in the world, and your favorite character is on your lunchbox and on your T-shirt, and then also in a comic book then also in a movie something like that. That seems like how the world is working-how the world is integrated. In some ways it’s my six- or eight-year-old brain trying to play the game or trying to react to how the world is. Then it’s like Charles and Ray Eames; they were like that. I like how they like disrupted our adopted ideas of high and low, important or unimportant, of serious entertainment. Or Fischli and Weiss, where each new piece of theirs wants to sort of blow up their artistic identity, explode the confines of a “career.”

BF:Â How do you mean? (LEFT: SONIC YOUTH POSTER, 1995)

MM: To make it more subversive and disruptive and exciting and real. I as “Whoa, they did that? How did they do that?” I remember Hans Haacke showed us their film, “The Way Things Go,” the sort of mousetrap film when I was in college.

BF: When you went to college at Cooper did you think you were going to any one thing in particular?

MM: No, and that’s why I went to Cooper. Because I kind of had a sense that somehow I knew I wouldn’t be able to do one thing. I was in a band and I thought that was going to be my biggest thing. I thought I was going to be a professional skateboarder or in my punk band. Both failed. So when I was 18 like my life had already passedâ??

BF: You felt like you peaked.

MM: Those were two things that I really wanted, so I tried to make it work. Cooper is one of the only colleges where you don’t have to declare a majorâ??at RISD you have to declare a major by your second year. And then it’s a pretty narrow thing of illustration or sculpture. All those categories are just careerist, bourgeois, capitalist vibes that you have to fit into. They aren’t really about creativity. By then I had read enough Bauhaus stuff. The Bauhaus was totally against that. Bauhaus is totally against the idea that a painting is real and a chair is utilitarian and not as important. At Cooper you didn’t have to declare a major and I picked the school largely because of that.

BF: It worked so perfectly then.

MM: Kind of.

BF: Well for a while you worked for a design firm.

MM: I worked for M & Co. for not very long, for less than a year. I worked for this place called Bureau, which was Marleen McCarty and Donald Moffett. They were artists: Marleen was having shows at Metro Pictures; Don too. They were in Gran Fury, but they also had this design thing.

BF: You couldn’t necessarily do it that way today.

MM: A lot of people were trying to rock the many-career thing. The work that they did at M& Co., they weren’t slumming or shitting where they ate: It was serious design that they didn’t hide and it was part of their overall practice.

BF: That’s a good survival strategy, if you just want to do creative stuff to do-

MM: We left cooper in the late 80’s. It was Mary Boone and SOHO was at its peak. We knew a lot of people who where breaking Julian Schnabel’s plates or painting David Salle’s paintings. We were disenchanted and that scene seemed so horrendous-and the opposite of being creative and being weird. So a bunch of us got into graphic design, not to be in that exclusive world but to be in the public. To get a poster on Broadway was the goal and the museum wasn’t the goal. We were young enough then to think that would be totally satisfying. It wasn’t a way to pay for your art thing; it was to replace the art thing. To work in the public sphere seemed more ambitious project than working in the art sphere.

Â

BF: How long did it take you to want to get back to the art sphere? Did you do commercial stuff first?

MM: I did record covers, but right away-right after that I met Aaron Rose and that was totally a sideways hit with a car. Because there was a gallery but it was so unprofessional and so out of the art rhetoric and so uninterested in gallery sales creating wealth. It didn’t have anything to do with that. It was a weird accident: He [AARON??] was living around the corner and he had a skate show and I went to that and met him and then we became friends. So we had a show there and it felt so like I was part of a community. It was so small and nice it didn’t feel part of a career.

BF: At what point did you decide you wanted to make movies?

MM: I was 27-and if I were in college I would have said, “Oh, it’s so hard to make movies and I don’t know how to do that.” But I did like that it’s very public and it’s considered in the entertainment sphere. There’s more opportunity to surprise your public and it’s more emotionally based than critical. I was 25,6,7, and I see Thin Blue Line a film by Errol Morris and it’s very graphicy, and not like a normal film at all. At the same time I’m watching Jim Jarmusch and just because the films are so lo-fi and the acting is so-it’s great acting but it’s not that cathartic acting where you fall into the character. I relate to that much more than I would a Hollywood film. I started doing videos as a way to try and learn how.Â

BF: That’s where the videos came from-trying to get ready for the film stuff.

MM: It was a pipe dream at that point. Videos were exciting in their own right. I was into the Eames and they did those great short films. The big dream was to be able to expand it, but I would never have told anybody because it just seemed so pretentious and potentially not going to happen.

BF: That’s a good route. You did the short first? Well you did the documentaries.

MM: I did the short about Dave skateboarding, then I did Deformer and then I did a documentary about Air touring and I did Paperboys. All along while I was doing videos and ads I was doing longer pieces and more personal pieces.

BF:Â Thumbsucker was a total labor of love. Seven years of work, all told.

MM: MM: Six, seven, depends on when you count the end. It’s still going. Films are tricky because for years you’re getting told you’re about to make it and you’re about to be busy for four or six months or you’re about to be on tour for press. But these things tend not to happen, and meanwhile you’ve said “no” to many things cause you thought you were going to be busy, for years, for years this happens. That’s something that I learned on the first film that I have not done on the second film. The other way film can just dominate your time and identity is that they get so much more press. Films just automatically have a larger audience. And people in general kind tend to think a feature film is the most important thing I’ve doneâ??and this works on your brain, until pretty soon I start feeling I’m not doing anything real or serious unless I’m doing a film. But of course, that’s just a little dangerous lie.

Â

BF: This time around you’re working on a film and you’ve been having a lot of waiting. But you’ve been doing other stuff. You’ve had two, three shows this year?

MM: I ended up doing a feature length documentary while I was writing it. I’m also trying to slow down in my own life and enjoy sitting more, which is getting easier. I’ve definitely been less beholden to the film gods. Waiting for an actor or a particular financier and it can go on for months and months. I’ve still waited more than I ever wanted to, but I think I did a little bit better this time.

BF: You’re at the mercy of all these forces.

MM: People ask “How does doing a film compare to doing an ad?” Well, when you’re doing a commercial you don’t have sell tickets. You have a captured audience. Which is actually completely rare and great, it gives you a lot of freedom. When you make a film, you have to do advertisements for the film.

BF: In doing the book and revisiting these two and half years of work and things, did it feel cathartic?

MM: I had to find stuff. Luckily I kept all my discsâ??I had to buy a Syquest machine. I have a lot of flat files, but I just stick shit in there and never look back. I had to go look back and it wasn’t totally pleasant. But one it’s really nice to have everything in one place. It’s a tremendous hit of Xanax on your soul. I’ve said it a million times to the press, but looking back at everything, I see yeah these themes are running through the whole all the time. That was weirdly both embarrassing and reassuring that there’s a me in there.Â

BF: Did you see instances where you were posing a question that a later work answered?

MM: Yeah totally. When you’re in your twenties, its so easy to pose one-off questions about yourself or the world that you don’t feel the need to answer. When you’re 400 years old, you’re more willing to get in there and wrestle with it and not just do a drive by.

BF: Are any of them answered definitively at this point?

MM: No, but I have always talked about loneliness and sadness. At the beginning it was a mystery to me, But now I feel like I know a whole lot about it. [LAUGHS] Why I felt that wayâ??years of therapy later I know what I’m talking about and I still want to talk about it. At the beginning of my career I would do a poster with a dead bird that said “Sad,” on it. So it goes from that one liner to Does Your Soul have a Cold? [2007], which is a feature-length documentary about depression and totally getting into it as a cultural historical event. So that shows you how it grows. [LAUGHS]

Mike Mills Graphics Films is now available. On April 2, Mills will sign copies of the book at the opening of LA Art Weekend, at the Purple Lounge at the Standard, Hollywood. At 7:30 PM he will screen films at the Hammer Museum, to be followed by a conversation with Kate and Laura Mulleavy. RSVP required for both events.