Larry Clark’s America

LARRY CLARK IN LOS ANGELES, SEPTEMBER 2016. PHOTOS: CARA ROBBINS. GROOMING: BLONDIE/EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS MANAGEMENT USING KEVIN MURPHY AND MURAD.

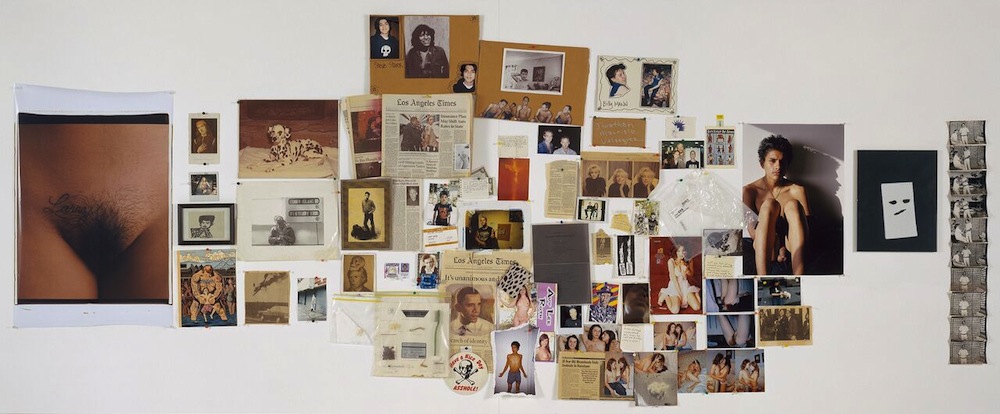

In 1995, Larry Clark cemented himself in America’s filmic memory with Kids, a stark tale of sex-, drug-, and angst-fueled adolescence. But his candid approach—at times brutal, always unshrinking—extends far beyond his directorial mode. In 1961, the Tulsa, Oklahoma native began taking his “first serious photos” (according to Clark) in his hometown, and in the decades since he has continually expanded the margins in which he explores “youth culture.” There’s Teenage Lust, a bound collection of intimate, nearly pulsating black-and-white portraits; Tulsa, a disquieting set of images (also in book format) haunted by the looming specter of abuse; and most recently, his never before seen “Heroin” series, a set of visceral, abstract paintings.

“DTLA,” the inaugural show at UTA Artist Space—presented in association with Luhring Augustine Gallery—recognizes each of these mediums and marks the largest display of Clark’s work in Los Angeles to date. It’s a fitting demonstration of the 73-year-old’s oeuvre thus far, revealing seldom seen works (including Tulsa’s 16-mm film counterpart) and new collages and paintings (such as the aforementioned “Heroin” works).

Days ahead of the show’s opening last weekend, Clark spoke over the phone with actor and screenwriter Owen Wilson about Kids, learning how to skateboard at age 50, Tulsa, self-medicating with speed in his youth, and more.

OWEN WILSON: Larry, I’ve got to tell you, I’m not just going to be throwing out softballs to you. This is going to be hard-hitting.

LARRY CLARK: Good, I wanted that. I’m a tough guy, so go for it. Don’t be embarrassed or shy about asking anything.

WILSON: Brace yourself. So let’s start with: What’s your favorite color?

CLARK: [laughs] My favorite color is green.

WILSON: Even though we’ve never really hung out—we’ve just barely met in passing—I guess we have a sort of funny connection in that our mothers are both photographers. My mom, [Laura Wilson,] she worked on that Avedon [series], In The American West.

CLARK: Mhm. [pauses] I would say of all the photographs I hate in the world, those I hate the most.

WILSON: [laughs] I know!

CLARK: The New Yorker asked Avedon to photograph me after I made Kids and I said, “Fuck no, man! I wouldn’t let that motherfucker photograph me for nothing.” And [Helmut] Newton had just moved to Monaco and taken all the contracts with The New Yorker, so Helmut photographed me in Cannes in 1995 and it was a full page in The New Yorker. It’s the best picture of me ever made, just brilliant, because Helmut was a brilliant photographer. But Avedon’s stories of all of the famous people, of Humphrey Bogart and all that stuff, were great. I, like everybody else, enjoyed that work a lot. And the photographs of his father dying I thought were powerful. But in In The American West he was making fun of people, that’s where it comes from. And I hated him for making fun of these people, man—just horrible, horrible photographs. His son said that his father was actually quite a shy guy and hardly left New York, and so when he went out to the American West it was like going to Mars for him. He was photographing people like they were from Mars. I thought he was out there goofing on those people, because if you look at those pictures they’re the most unflattering pictures of people. I could never make a picture of someone like that and show it, I would never do that. I thought they were hurtful. But when he told me about his father going to the American West and for his father—for Richard—it was like going to Mars and meeting these people were like meeting Martians, I at least understood more; I understood where Avedon was coming from, because I had no idea he was coming from that place. I was very happy to meet his son and have his son explain it to me. I still hate the pictures, but at least I know where Avedon was coming from.

WILSON: You talk about that feeling that that they were just out there goofing on these people, making fun of them, and one of the things that I really appreciate about your photographs and Kids is that there’s a generosity of spirit in the way you see those people. I know you worked with Harmony Korine a little bit on Kids, and [Korine’s] movie Gummo [1997] I had a problem with because I thought that was making fun of people. When you feel that—it sounds like you share that with me. It just makes you uncomfortable and it makes you feel like they’re treating people like freaks and taking away their humanity.

CLARK: Well, I’ve been a photographer for my whole life and I’ve done everything with photography that I felt I could do, and I always wanted to be a filmmaker. But I was always too fucked up on drugs to even think about someone giving me a couple million dollars to make a film. So I cleaned myself up and I decided I wanted to make a film. Most of my work had been autobiographical and I wanted to make a film about something that I didn’t know anything about. And I had two children, my son was about nine and my daughter was six, so I wanted to make a film about contemporary teenagers that had never been made before, a real film. When I was growing up, all the films about teenagers were played by Tony Curtis or John Cassavetes when they were 27, 28 years old. We would see these teenage movies in the theaters and I would say, “They don’t look like they’re my age at all.” So I wanted to make a movie that was real and I wanted to make a movie that wasn’t about me. I wanted to explore something I never knew anything about: contemporary teenagers. Visually, I thought the most exciting teenagers were the skateboarders. I started hanging out with the skateboarders for about four years, and if you’re going to photograph skateboarders you can’t run after them, you’ve got to learn how to skate. So at about 50 years old I learned how to skate, and skate fast enough to keep up with them and hold my camera. I skated with them for three or four years, broke my shoulders, and bombed hills that they wouldn’t even bomb, so I got a lot of props, a lot of respect from them. And finally after about three years they treated me like one of the skaters, one of the kids. They trusted me. They let me into this secret world that no adults are allowed into. No adults were allowed in that world, because you remember when you were about 12 or 14, you had a separate world with your friends that your parents, your teachers, nobody was allowed in except your buddies, right?

WILSON: Right. I grew up in Dallas in the ’70s, where it was really that your parents would open the screen door in the morning and you were gone all day just cruising around on your bike—looking for mischief. I always felt that Charlie Brown did a good job of that, that they never showed the adults, you just hear that “woh-woh” and that’s what it’s like being a kid—you are really removed. And that movie, you guys did a great job with that.

CLARK: Yeah, it was like the secret world of kids. I wanted to make a film where it felt like you were privileged—that you were eavesdropping on this world that there was no way you were going to have any access to except through my film. And my hanging out with these kids for three, four years—I got the idea for Kids all from true stories. The only made up part was Jennie, the girl who gets HIV from her first sexual encounter. Everything else in the film actually happened. I wrote a little two page treatment of the story: it starts here, it goes here, here, here, this happens, there’s a fight, this happens, there’s sex, and the parties, and then it ends. It was just a page and a half of the story, that’s all it was; then I was ready to make the film. But I didn’t want to make a documentary, so I had to add some kind of narrative. I thought back to the girl tied with rope on the tracks with the train coming, and that was the character of Jennie. … It’s just a day in the life, and the next day life goes on. I felt that the screenplay could only be written by someone from the inside—a kid. Because when I did my first book Tulsa, I was a kid in a secret world photographing from the inside. There was this New Yorker cartoon where the whole cartoon was a guy in hell with a camera taking pictures. And you can’t take pictures of hell from the outside; you have to be inside hell. So I thought, “Gee, I wish a kid could write this screenplay for me, but I don’t know any kids that are writers.” But I had met Harmony a year ago, and he was 18 and had just graduated from high school … and he told me that he wanted to be a screenwriter and make movies. A year later when I had the idea for Kids, finally, I called him up and—he had told me he had written this whole twenty minute screenplay—so I called him up a year later and said, “Hey Harmony, it’s Larry, I remember that little screenplay you wrote… ” He brought it to me and I read it and it was incredibly good. Most people that age would write a screenplay to please their teacher or to please any adults. Well, this screenplay was not going to please any adults. So I asked him to write Kids, and he said, “I’ve been waiting all my life for this,” and went to his grandmother’s house in Brooklyn and basically wrote the film in less than a month. And I shot the script.

People think the film is improvised, [and it isn’t] except for one little scene of the four boys on the couch. They showed up one night and I pushed them on the couch, and told them to start talking, and they were smoking weed and high as a kite. And they were 12, 13 years old. That’s in the film and that’s the only improvised scene. Every other word in the film is scripted by Harmony. He wrote a brilliant screenplay. But Harmony was a kid, he was kind of a mean kid, and he was entertaining because he was funny but he was kind of mean. When he made Gummo some of that meanness came out. … Harmony was young and being that young, it shows in Gummo that he is goofing on people, which I would never do. But Harmony is a brilliant screenwriter and did a brilliant job with Kids. And I love him, Harmony’s okay.

WILSON: For Kids, were there movies that you drew inspiration from? It sounds like you drew inspiration actually to make movies not like the ones you saw.

CLARK: Exactly. And if you’ve seen my books through the years, I’ve always been a storyteller. My first book, Tulsa, I wanted it to be a film. I wanted to make a film, but I couldn’t bring any outsiders in, and I actually went down in ’71 with a camera and sound equipment by myself and was going to try to make a one-man movie, which is impossible to do. I came back to New York and then I went straight back to Oklahoma with my Leica and jumped back into my old world, and finished the last half of the book in 1971 because I already had 1962 through 1968. I knew what was missing from the scene; I knew what I hadn’t been able to photograph before; I knew exactly the photograph that I needed. I didn’t know when they were going to happen, how they were going to happen, where they were going to happen, but I knew they were going to happen somewhere sometime and I was going to be there. I finished the last half of the book in ’71, ten years after I had started. I had never published a book; I was just practicing photography. The first half of the book is me practicing my photography and we were in these small rooms, it’s very intimate, and I had a 50mm very close to people. We were in these little rooms shooting amphetamine, it wasn’t even called speed back then, it was so early. And then later it turned to methedrine because they started making Desoxyn, that was pure methedrine in a pill. That’s what all the Andy Warhol people started doing back in the late ’60s, when all the speed freaks started and the word speed was coined.

WILSON: You have great titles. Did you come up with Tulsa, Teenage Lust, Kids, and Another Day in Paradise?

CLARK: Actually the title of Kids came from a writer who’s written a lot about art and he’s written novels; Jim Lewis, he’s an old friend of mine. And when I had the idea for Kids he came over and helped me write the treatment, the one and a half pages of the story. And I said, “You know, I’d like to make a 24-hour movie and have it be like a roller-coaster ride,” and he helped me put the treatment together that I gave to Harmony. And the title of Kids came from him. He said, “You should call it Kids,” and I said, “Why?” He said, “Because you refer to all of them as kids.” So I said that’s a good title. Tulsa was my title. Teenage Lust was my title. Another Day In Paradise was an unpublished manuscript by an ex-convict junkie named Eddie Little.

Eddie was an ex-convict, a heroin addict, and someone sent me his unpublished manuscript, which knocked me out. So I flew from New York to Sun Valley, in the hottest part of the year—it must have been about 120 degrees in Sun Valley—at the worst, lowest rehab of all time. This house full of ex-convicts, these big burly guys covered with tattoos that were either going back to prison or going before judges, so they were trying to clean up to go before judges. I met Eddie there. He had a lot of charges against him and he had to go to trial. And I went and met him and told him I’d like to option his manuscript and make a movie out of it; it hadn’t been a book yet. After I did that it was published as a book. But I took his manuscript and shot Another Day In Paradise and then made up half of it as I went along, so I completely fucked with his manuscript, because it wasn’t a screenplay. … I mixed myself and characters I knew from Tulsa with his characters from the Another Day In Paradise manuscript.

WILSON: How did you get the Dylan song, [“Every Grain of Sand”]?

CLARK: Bob likes my work and I just wouldn’t stop. We had 20 no’s and they wanted a lot of money and we didn’t have the money, and I wouldn’t take no for an answer. It’s a great, great song. It was my favorite song. I made a tape on a loop back then, because we had tapes, and I would play it in my studio over and over again all day long—like 200 times a day, every day. I wanted to do the film with that. … It took a while but I never give up; if I want something I do everything to get it.

WILSON: You said that in preparation to access that world of Kids you became a good skateboarder. Did you play sports when you were a kid? What did you want to be when you were a kid?

CLARK: When I was a kid, I wasn’t good at sports but I played sports. We used to play tackle football in the park every Sunday—really rough tackle football, dressed in our street clothes. Tough, tough, tough games. People were really trying to hurt each other as much as possible. You had to be fast because otherwise some shitty little kid… So I was tough that way, but I wasn’t like a real athlete at all. And learning how to skateboard at that age, [50 years old,] is completely crazy, reckless, and stupid. But I did it. I learned how to skate, I couldn’t do the tricks, but I could certainly skate fast enough. I could keep up with anybody and I could bomb hills and I could hide behind my camera. I had my Leica with me. And I learned how to fall so I wouldn’t hit my face. I was bombing this hill once, and I was with Mark Gonzalez, a really famous skater, and Mark wouldn’t bomb the hill. He said, “Larry don’t do it, don’t do it.” And I said, “Ah, fuck it.” And I jumped on the board and bombed the hill. But I forgot to tighten my trucks, man. And on the corner way down the hill, it was off of Sunset, it was by that club that Johnny Depp club—

WILSON: The Viper Room.

CLARK: Yeah, where Sunset goes straight down for a while—it’s almost an un-bombable hill. But I forgot to tighten my trucks. Coming about a quarter of the way down the hill, I’m getting the wobbles and the wobbles and the wobbles. So I prepared myself and I just said, “Keep your head up, keep your head up.” So when I went flying like superman I kept my head up. I skidded on my chest and my shoulders and my hand, and my hands were raw. I broke my shoulder, really fucked myself up. But I kept my head up, I kept my chin up, my chin or face never hit the pavement, so I was lucky in that way. I have mad respect for Mark Gonzalez and everybody like that. That was just stupid. I think I had taken a handful of Valium or something, drank a six-pack before, so I was probably fucked up when I did it, but it was pretty crazy. I paid the price of learning how to skate at almost 50 years old, to get to know these kids and make the film.

But no, I wasn’t like a great athlete. When I was a kid I was a skinny, scrawny little kid. I was the latest bloomer of all time. And I started like a maniac, I had ADHD but no one knew what that was back then in the ’50s. I was in the principal’s office, and I wasn’t a bad kid, I just couldn’t sit still. I was always vibrating. When I started shooting speed, amphetamine, when I was 15, almost 16, it actually calmed me down. Now they give kids speed for ADHD to calm them down; they give them Ritalin. I was over self-medicating back when I was a kid and didn’t know it. I would take a gigantic fucking shot of speed, or amphetamine, and in the Tulsa book you see guys flashing and rushing, running across the room. But it would just calm me down. All of the sudden I would be the most calm person. I would just watch for the next photograph.

“DTLA” IS ON VIEW AT UTA ARTIST SPACE IN LOS ANGELES THROUGH OCTOBER 29, 2016. FOR MORE ON LARRY CLARK, VISIT HIS WEBSITE. OWEN WILSON IS AN ACTOR AND SCREENWRITER WHOSE FORTHCOMING FILM ROLES INCLUDE MASTERMINDS AND BASTARDS.