Gogy Esparza’s Novelty Act

Despite the universal appeal of the new beginning, few take proper advantage of the promise of a fresh start. Artist Gogy Esparza is the rare case who does not take his clean slate—or, in his case, palette—for granted. Hailing from the projects of Massachusetts, Esparza came to New York on scholarship to study art at NYU’s prestigious Gallatin School, leaving the dire straits of street life behind. Though his work—an assemblage of fine art, photography, and video—marks this departure through the proficiency of his technical ability, it remains shaped by the premature disillusionment of a boyhood survived in a world where crime and poverty ran rampant.

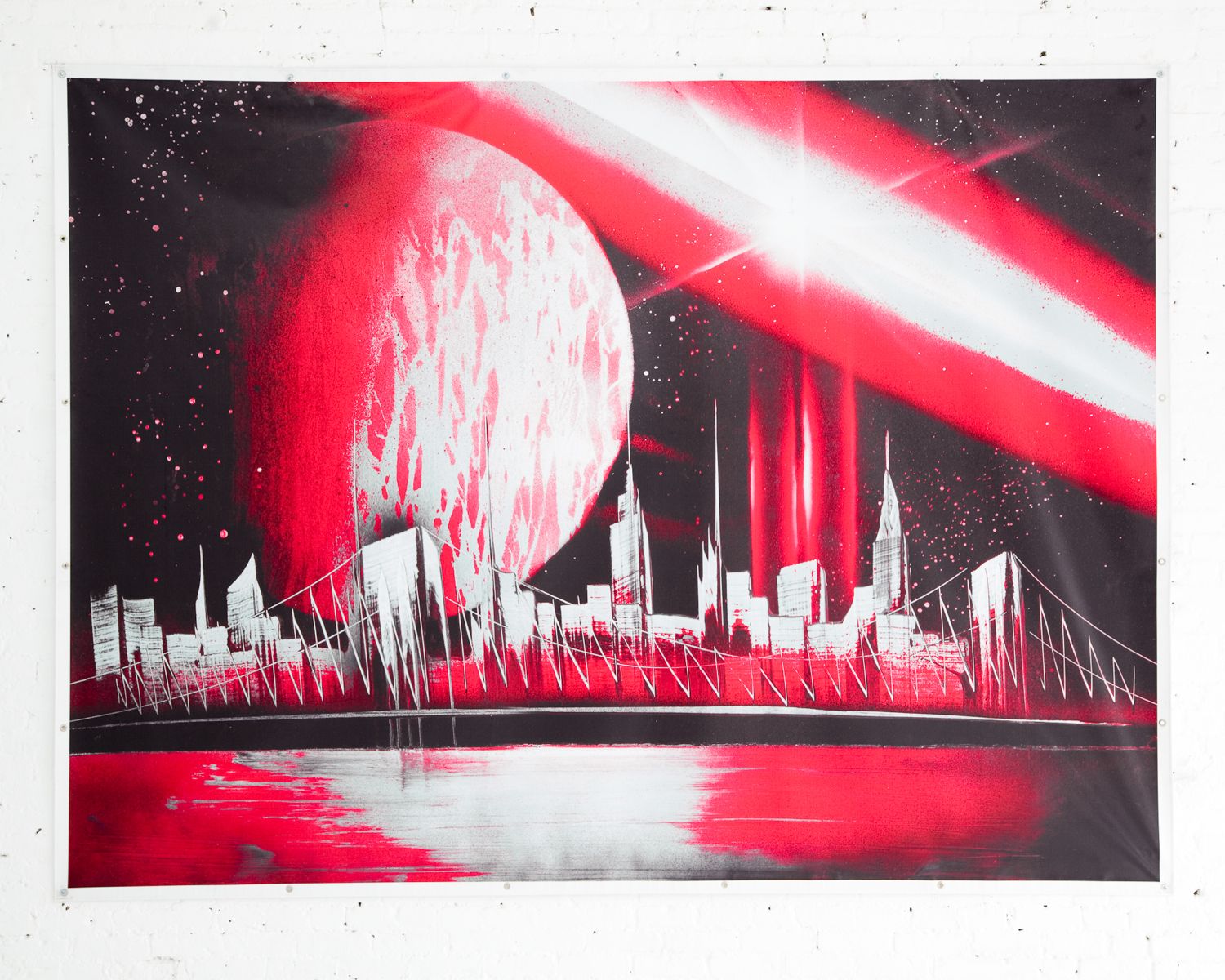

From photographs illustrating glints of vulnerability in the eyes of the seemingly most defiant men to his use of “temporary sculptures,” Esparza’s aesthetic affixes light to dark, showing just how closely tied the dualities of life can be. Today at Magic Gallery, his “NEW NEW” exhibition, with supporting work from fellow multipurpose artists Peter Sutherland and Maggie Lee, opens. It’s a show that seeks to hit “that sweet spot” between broken backgrounds and promising futures, while, most importantly, conveying the importance of appreciating the here and now.

This weekend, we met with Gogy at his new Chinatown studio to discuss what he could tell us about the show. “You wouldn’t believe what this place looked like a few weeks ago,” he said proudly, stepping into his freshly painted, all-white space. We took off our shoes. “It’s the new New.”

NOOR BRARA: How did you come to meet Peter Sutherland and Maggie Lee?

GOGY ESPARZA: It was super coincidental. I’m Ecuadorian, and we moved from Ecuador to Worcester, Massachusetts, which is a very big industrial town. My aunt has had a salon there for 30 years, where I worked as a kid. When I moved to New York at 17, I brought the trade with me, and started working at this salon on Essex Street called Frank’s Chop Shop. And it was the coolest, first of its kind, new-school barber shop where you could get perfect salon techniques done but still get a barber environment— sometimes guys feel intimidated by that, that super salon-y sort of thing. So I was working there and there was this store around the corner called aNYthing—”a New York thing”—that was this really downtown clothing line and lifestyle label, where Maggie was working. So I just met her there, kind of organically. And then when I was in school, while also cutting, I put together this self-published zine of photography. I actually ended up doing a show for it in Tokyo through these Japanese guys who I was cutting hair for on a photo shoot. I went there a few times to soak it in, and Peter was on one of the trips. He came to my installation and liked it. I will go on record and say that that man is The Man. He’s the Yoda.

BRARA: The Yoda! Yes. You can tell that from his pictures, in how he’s able to capture these sublime moments in nature. Especially in how he renders sunlight. It’s like he’s always looking to photograph a feeling instead of just an image.

ESPARZA: Totally. He’s like the Phil Jackson Zen Master, you know, he sees it all. So, for him to see something in me has been one of the highlights of my life so far. He’s seen me through everything, from then to now. I think the key to anything is being really observant and immersing yourself in the energy of everything, and I try to do that whenever I’m around him. So I reached out to Peter and I told him what I was working on, and asked him if he wanted to do a show with me, and he said, “Yeah, definitely.” It was the same with Maggie.

BRARA: So it was your idea and they kind of jumped on board. What came first for you, the theme or the work?

ESPARZA: Probably the work. I think they knew emotionally and in my soul where I was at the time. “NEW NEW”—it’s a completely white space, it’s a brand new start for me. It’s my own individual venture. I mean, I don’t want to throw this in people’s faces, but my family’s not from here, and they’ve been working in factories for 12 years, busting their asses to put me in a good position. I don’t take that lightly at all, so I tried really hard, and Peter and Maggie knew that was the energy I wanted to bring in. They had their own mediums they were working with at the time, so they started tailoring their work around my theme. I sort of want the whole thing to be a surprise, so I won’t say too much, but it’s all about where we’ve come.

BRARA: You’ll each be showing several mediums since all of you are multipurpose artists—you photograph, do zine work, sculptures and installations. Can you tell me a little bit more about the specific content that these forms address?

ESPARZA: I grew up in the projects of Massachusetts, which was actually really diverse. There were a lot of Latinos, African-Americans, Vietnamese, and Chinese, and it’s not as segregated there the way New York is. So I grew up in a melting pot, but it was essentially in the ‘hood, I guess. And all of my work references that. It’s in my soul, and a lot of Catholicism and spirituality is part of that, too. For me, it’s been my agenda to make sure that I speak to what I know. I feel like the culture that’s taken from the streets is always appropriated in so many ways, either by people that don’t really live it or understand it. A huge part of the point of this work is to pay the proper homage to that culture, but then to elevate it to the presentation I think it deserves.

BRARA: Yeah, I think urban life is often sensationalized in art, and I didn’t really see that in your work. It’s a much more straightforward and critical presentation. I was also thinking about the title of your show, and this sort of American culture cliché and obsession we have with new beginnings. I was wondering if you thought about how your work plays into that larger life theme, and if you think people can truly have new beginnings.

ESPARZA: I definitely think they can. But, without saying too much, here’s an example of the paradox of that: the sculptures that I’m doing are temporary. They fade away. They won’t last past the opening. So I think I’m quite aware of how life works, and how temporary or fleeting newness, and success can be. And some of the work speaks to that. I have ice sculptures, and they crystalize a certain moment and kind of energy for me, but then I know that that moment will dissolve. That’s part of the process; light eventually gives way to dark times, and you have to face them. The ice melts.

BRARA: That’s so interesting, to use ice to literally convey ephemerality.

ESPARZA: And I think that’s why I’m so keen on staying true to what’s real. I of course have certain benchmarks that I want to pass and dreams of where I want to be as an artist, but I’m still cutting hair downtown—I haven’t given that up. And so, in addition to the art crowd, a lot of people that are coming to the opening are people whose hair I cut for an hour every day, who really know who I am and vice versa. That’s the energy I’m bringing, and what I place emphasis on—you have your dreams, but you’ve also got to value what grounds you.

BRARA: Right, it’s optimism and realism, side by side.

ESPARZA: Yeah, and I think that’s in my photography, as well as Peter’s. You know, you see the optimism, but at the same time it’s very cognizant of the fact that we should live in the now. So, we’re very similar in that way. He’s from Colorado, and his work is also about capturing the hardness of where you’re from, but he also shows how beautifully that can be done. He’s always on the road traveling with his wife, seeking out these ethereal moments in the natural world, finding those visceral spots of light in life’s darkness. And he’s so positive and he believes in them, but he also knows it’s part of this larger thing. And I think Maggie is really good at doing that too. Her work is feminine and can be seen as dainty, but it’s still got that tinge of aggression and understanding.

BRARA: One of the things I noticed in all of your photography is that none of you seem to try to force meaning or purpose into your images. You’re more concerned with taking an honest picture of whatever’s right in front of you. An example that comes to mind is the picture you took of a guy sitting on a motorbike with sunrays in front of him. Instead of trying to shoot from a different angle, you put them center stage, and what you’re left with is only the outline of his silhouette—his image and expression have been entirely blocked off by sunlight. What was the message behind that?

ESPARZA: That body of work was kind of a lead-up to what this show will be. It all ties back to the subcultures within the ‘hood that are completely misunderstood from the outsider’s point of view, who doesn’t really understand the souls of these men. For most, you can’t ride a dirt bike on the streets of New York without a helmet, doing tricks, going 60 miles per hour, dodging the cops and making lots of noise. But for these men, it’s a release, a sense of rebellion that’s entirely theirs. And what they do on that bike is magic. They’re driving on these unpaved roads, wanting to get faster and more cunning. They do wheelies, they wave and yell, and they have this style that’s beautiful and ballsy and it’s a big “fuck you” to whatever’s going on around them. And I was attracted to that, because a lot of times that’s the same type of show my work is about. I captured that style because it’s also mine —a love glimmers and glints and bravado, everything that’s part of that brash ‘hood life glamour. I love it.

BRARA: So, it was sort of like a salute.

ESPARZA: Right, to aspects of that whole culture. I think the assumption is always that, with guys on the street, they have nothing and then they go out and waste their money on material things; a pair of sneakers, or jewelry, or new clothes. But the thing is, we don’t know anything else—our world is confined to that 10-block radius. Therapy isn’t really something that’s written into that way of life, so the thinking is that, I can go and talk to someone for three hours, but it might not do what I want it to—or I can buy something and drive around looking fly, and that’s guaranteed to make me feel better. And that’s what my work addresses with respect to these guys: you’re so hurt and torn up by all the negativity that you have to show what you have, you go to what you know. And it’s sartorial, that you have to display yourself in that way. You might be poor, you might be down and out, but you can’t look like you are. And while I’ve left all of that, it’s still very much part of what I can identify with, and I don’t really want to let it go. So yeah, this is my new beginning, but it’s tied to its context.

BRARA: It’s about where you’ve come, without having abandoned your former life or identity.

ESPARZA: Exactly. And I’ve worked a lot on the polish and presentation of that, because I didn’t know how to cut and map prints and frame them or produce a sculptural piece before school. There are rules to everything, and the work needs to be presented in a certain way to be alluring to an eye that can distinguish between just “hipster, art-school kid work” and what can actually be shown in a gallery. So I used those skills to capture my stories.

BRARA: Can you tell me just one of the stories?

ESPARZA: Okay, okay. Going back to that whole material culture thing: When my brother’s daughter was born, he would buy her a new pair of baby pink Timberlands every time her feet grew—she was his inspiration, his new beginning. He spent all that money, but we had life again and we had hope. For one of my works, I froze a pair of baby pink Timberlands in an ice cube, and placed them on top of a pedestal. So that’s part of the show that speaks to that message—it’s that amazing moment there, but then it fades and you have the memory. That child is my life, she’s my re-birth, and a lot of the work is about honoring moments like that.

BRARA: And that’s really the theme to me. It’s not necessarily about brand new beginnings or starting over, but chasing those little seeds of life and making them count. What’s the takeaway of the show, in a nutshell?

ESPARZA: I think it’s really about taking life as it comes—I’m a dreamer, and there’s always going to be both good and bad, I’ll always waver between who I am and who I was, and in a way the show is sort of about reminding myself of that. Right now, it’s to celebrate the moments of new, the moments of now, where I am and what I came from.

“NEW NEW” IS ON VIEW AT MAGIC GALLERY, 175 CANAL STREET, FIFTH FLOOR, TONIGHT, MARCH 19, THROUGH APRIL 18.