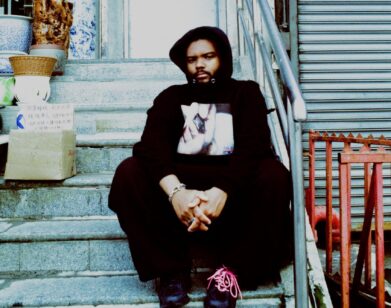

Discovery: Hugh Scott-Douglas

The characters in the 1920 silent thriller The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, in which the title character keeps a somnambulist captive in a cabinet to carry out murder in his sleep, spin hypnotically around a soundstage filled with painted set pieces. They walk up stairs and hallways and rooms as if the goal wasn’t simply seeking out a mysterious killer, but in the journey itself. Brooklyn-based artist Hugh Scott-Douglas has named his first solo show at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, for the movie, as a tribute to the circuitous nature of this odyssey [opens Jan. 12].

In his work in cyanotypes, laser-cut canvases and slide shows, Scott-Douglas begins with a patterned motif, which he threads through each of his different series. He begins with the cyanotype, an outmoded photographic printing process that relies on sunlight to create blue-toned images, to develop these patterns on a canvas. The original pattern is then scanned from the cyanotype, and laser-cut into another canvas. The laser-cut canvas is then housed in an upright, custom-built road case (the kind you might see holding a musician’s gear at a rock concert), which serves as a mobile frame on wheels. The cyanotypes are also the basis for a slideshow, where the blues are transferred into photographic gels that are cut into slides to play in a slide reel.

The remnants of this process—the cyanotypes in the road cases, the laser-cut canvases, the slideshows—are all gathered and displayed, creating a sort of real-time signature on the gallery, whereupon Scott-Douglas can gauge the work; because even then, the gallery is all a part of the continuous process.

AGE: 24

HOMETOWN: Cambridge, England

CURRENT CITY: Brooklyn

SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE: If there is a grand thesis to my practice, it draws from trying to negotiate the currency of image. It’s interesting to look at images that are both hyper-inflated and images that are deflated. I acknowledge cinema as the most inflated form of spectacle, and often draw from filmic examples, not so much for pictorial content of a film, but for the mechanics of the picture.

FRAMING THE FRAME: Mise en abyme is a simple phenomenon: things reflect in on themselves, or framing the frame. I was looking haphazardly on the Internet for examples from cinema that employ mise en abyme, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari comes up often in this regard. Its sets were all paintings on flat surfaces, so to create perspective everything was using a fictive pictorial space as the thrust. For the press release I’ve included a pictures of a door from the set, which carries on ad infinitum, black frame after black frame.

But also, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is hailed as the first film to use mise en abyme narrative, or a dream sequence. My interest in the film developed before I had ever even seen it. This body of work is not really about that film; it’s about the mechanics of that image—what gives that picture value.

RECYCLE, REUSE, RINSE, REPEAT: In the film, we have this sleepwalker, activated upon the opening of the cabinet. There’s something interesting about that relationship to narrative structure. In this show, the laser-cuts function the same way. They’re derived from files based on previously made cyanotypes that I’ve archived the image from. I see them as kind of “activating the sleepwalker” in the same way. There’s this dormant file, and then you open it up and put it in this case as a way of displaying it, and it comes alive again, which is a nice way of giving a second meaning to the laser-cut works. It’s reinvesting value.

DURATIONAL AESTHETICS: The road cases are about exhibition design, treated as a structure that temporarily accommodates the display of a work. They’re part wall, and they’re also part frame. It’s an accommodating structure. There’s something that makes them about their contexts. They have a life span in the same way that the cyanotypes do.

METHOD ACTORS: I would say if there’s any sort of covalent bond that brings me and who I would establish as a peer group together, it would be methodology. The methodology is part an understanding of a material process, part research, part independent interest, or independent lexicon. [Brooklyn-based artist] Ben Schumacher, who I have collaborated with—he’s an extremely close friend—he has a degree in architecture; that’s where he’s coming from, whereas I would say I’m much more interested in the mechanics of cinema. But he’s establishing a very similar studio methodology.

CHROMA CHAMELEON: A facet of my work is chromatic. The cyanotype plate sits in the parking lot in front of my studio for 15 minutes. There are environmental factors that change ad infinitum as time passes—UV shifts, cloud cover increases or decreases, the position of the sun in the sky is moving—so the chroma of each cyanotype is slightly different, or sometimes vastly different, than the last based on that process. I’m using a computer-driven approach to amalgamating the chromatic value of each cyanotype, by reducing it to its most generalized blue. I do that just as simply as using the color picker tool in Photoshop.

From that, you have this very unique color, because the RGB value is just a number, it’s infinitely varied. It’s unique. However, as a way of quantifying that value, I transfer the chroma to a cinematic lighting gel of which there are not as many blues as there are blue tones generated by the cyanotypes.

They’re never perfect. There’s always a difference. The way it’s quantifying or validating chromatic value became to develop a relationship to a readymade or a marketable product that is a lighting gel. I cut the gels up into 80 slides, and then give each one a time unit in the carousel of 11 and a quarter seconds, which culminates in a total time of 15 minutes. So it returns to the same amount of time that went into developing the color in the first place.

Scott-Douglas’s work will also be featured in the group show “Pattern: Follow the Rules” at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State, opening March 21, 2013.