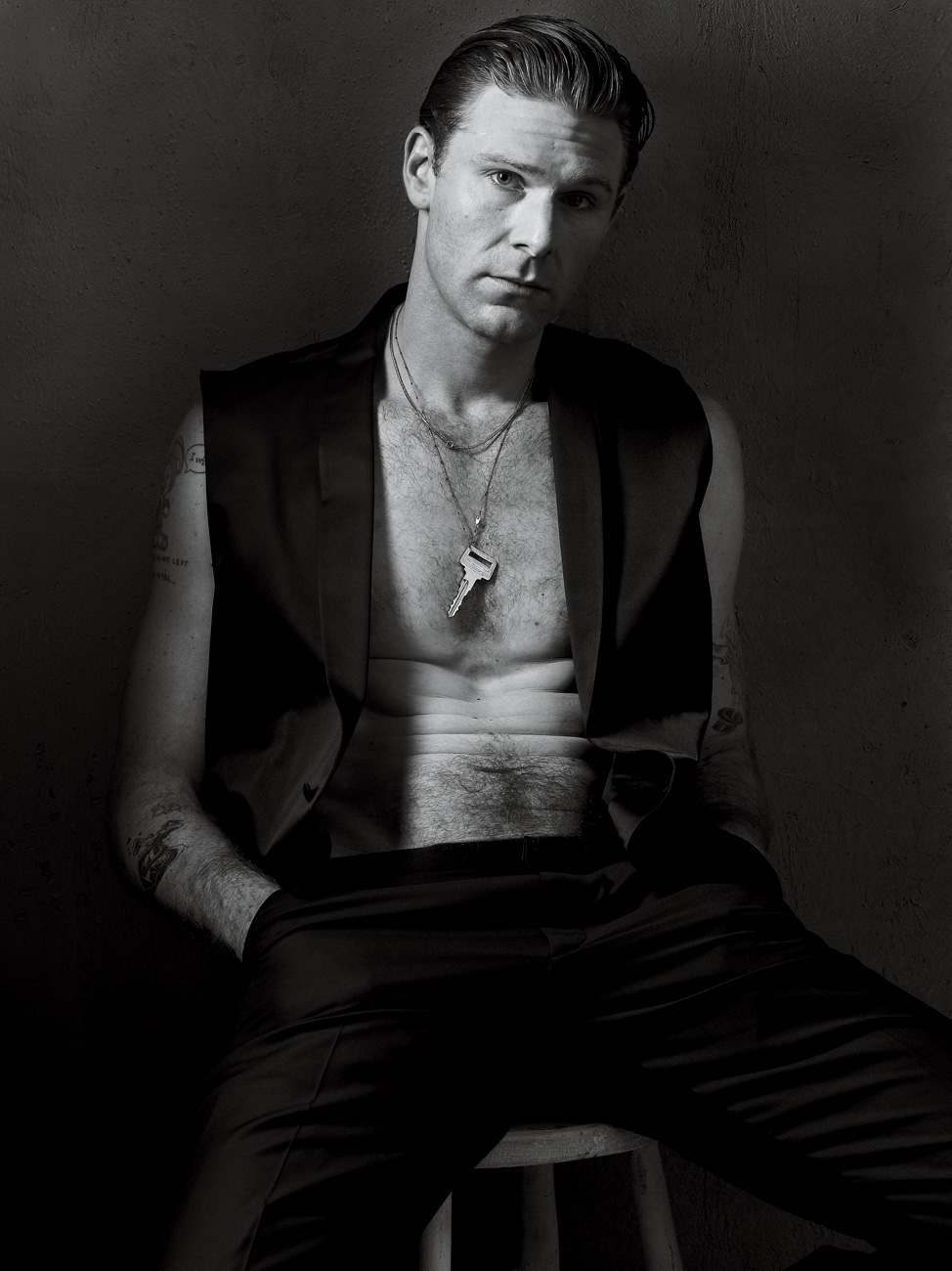

Dan Colen

In the disjointed art community of the early 2000s, there was one scene of brash, energetic young artists that emerged in downtown New York City and ended up defining the decade. For a while that group—at least from the outside—was spearheaded by photographer Ryan McGinley, whose early reportage photos of Lower East Side friends and dirty, young ne’er-do-wells perfectly captured the vibe and destructive glee of it all. As the decade progressed, other artists from this pocket of close friends surfaced: Dash Snow, Dan Colen, Nate Lowman, Aaron Young, and Agathe Snow, among others. On the outside, they seemed to trade primarily in nihilistic urban imagery, much of which they picked up from the skateboarding and graffiti communities, and critics were quick to peg them (and occasionally write them off) as heterogeneous inheritors of punk, Semina, Basquiat, and a ’90s mix of DIY and shock art. But the reality is that each of these artists was developing a style, technique, and an aesthetic direction that was entirely his or her own. Dan Colen has come out of this now legendary scene to become one of the most accomplished and promising multimedia neo-pop artists of his generation. He started out by producing a series of photo-realist paintings at his studio in the back of his grandfather’s antiques shop in Flatbush, Brooklyn, populated by magical fantasy characters. Another series of paintings featured Disney-style burning candles, where the smoke emanating from them contained disarming messages. He went on to explore spray paint on canvas, chewing gum as an abstract technique, and paint made to look like bird droppings. Now he’s mining the psychological joy-and-sorrow stimuli of confetti. Confetti suggests a party that is still going on, but for Colen, now 31, the endless party—with its wild nights, fast friends, and heavy toll of drugs—is largely over. In 2007, Colen and Dash Snow famously created the installation work NEST out of shredded phone books in Jeffrey Deitch’s SoHo gallery. At the opening, a party ensued that suggested the good times had just begun. Very few who attended could have guessed that they would end two years later with the tragic death of Snow, who overdosed last year after a long, hard-fought battle with heroin addiction. That loss was a hard blow to friends and artists in downtown Manhattan and no doubt had a sharp effect on Colen. But the New Jersey native has grown up on his own, and his work has matured to the point that he needs a sober focus to bring it forward.

This month, Colen, who first showed with Rivington Arms and is currently represented by the Gagosian and Massimo De Carlo galleries, will open an as yet untitled solo show at Gagosian in Chelsea, on view from September 10 through October 16. The event is quite a leap for a guy who once had to crash on McGinley’s beanbag chair when he visited the city before moving here in 2001. The show promises a mix of paintings, sculptures, and installations, including an upside-down half-pipe and the precise refabrication of all the bikes outside the Hell’s Angels’ club on East 3rd Street—knocked over Pee-Wee Herman–style. McGinley visited his childhood

friend Colen in the Tribeca studio he shared with artist and occasional collaborator Nate Lowman, just before his move to a larger space to prepare for his biggest show yet.

RYAN McGINLEY: I don’t really know where to start because I have so many memories of us together as kids. The first memory I have of us talking about art was when we were teenagers in the parking lot of that place where we used to play pool every night in New Jersey. I had my portfolio for Cooper Union in the back of my hatchback and I showed it to you.

DAN COLEN: I remember that. You made that painting of a computer-head guy.

McGINLEY: The computer-head guy was pretty good. I just told Chuck Close about that painting because it almost looked like one of his paintings.

COLEN: I remember that time really clearly because we were one year apart, like 16 versus 17, and you were already thinking about your future. You had a portfolio and I didn’t yet. But it’s funny because we never really went there before that moment. It was like, Oh, you got a portfolio? Now we can talk about art. Like, I wasn’t just going to show you the drawings I made of naked ladies.

It’s SUCH a WEIRD SELF-CONFIDENCE that an ARTIST HAS—to CONCEIVE of this THING that SERVES NO FUNCTION and SAY, ‘I’M GOING to REALLY WORK HARD FOR it and GIVE IT and IT’S JUST GOING to MATTER to PEOPLE.’ YOU REALLY HAVE to BELIEVE it ALL ON YOUR OWN. Dan Colen

McGINLEY: It’s so crazy to think that was already 15 years ago. That’s a 15-year dialogue about art—the longest dialogue on art I’ve had with anybody. In doing research for this interview, I went through all the art you’ve made over the years. I kind of stopped thinking about the art and started thinking about all the memories—where I was in my life when you were making your bird-shit paintings or your first baseball diamonds at RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] or the one that said “Jack.” And I thought about what I contributed, like when I’d come back from my road trips and bring you all those missing-persons or missing-cat posters and how those posters ended up on your rock sculptures. I almost started crying the other day when I saw one of those rocks at the Dakis [Joannou] show at the New Museum. I was standing there looking at every single thing on it—like I remember that day you wrote that person’s name with gum. It was an intense experience.

COLEN: That rock sculpture was from the show in Berlin [from the show No Me, September 2006]. That was such an awesome trip, but it was definitely the last of those trips. It was like we were burnt-out on being kids, but we made it work one last time. That piece is called Nostalgia Ain’t What It Used to Be, and it’s such a sentimental piece.

Dan Colen’s To Be Titled, 2010. Photo: Rob Kassabian.

McGINLEY: I remember that trip to Berlin. I remember going to that apartment that Javier [Peres] rented for everybody, and we all stayed up all night doing drugs. Neville [Wakefield] and I had made a plan to go to the art fair the next morning, and I got in a car with him at 10 a.m. after not sleeping and had a complete panic attack.

COLEN: [laughs] I remember you talking about that.

McGINLEY: We literally pulled up to the art fair and I immediately left, hyperventilating in another cab on my way back to the house. I was just trying to hold my shit together so bad, like totally feeling that at any moment I could have told the cab driver, “Take me to the hospital.” I slept for two days straight and then woke up to go directly to the airport back home.

COLEN: Is that when you were having a lot of panic attacks?

McGINLEY: No, there were just way too many drugs. It was crazy. I don’t think I drank that whole summer, and then suddenly just coming to see you and Dash [Snow] and Bruce [LaBruce] and everyone else, it was complete peer pressure and party antics.

COLEN: But you made up your mind before you got there, man. [McGinley laughs] It wasn’t peer pressure. We all came so ready, remember? You showed up . . .

McGINLEY: All right, next question. I wrote down a bunch of different memories. Like I remember when you threw that wood plank through a restaurant window at that Visionaire party in the Meatpacking District [2001]. All the people at V were calling me the next day asking if you were my friend, and I denied everything.

COLEN: [laughs] That’s a real night from my memory. Nobody knew who we were. We’d go someplace and you’d say, “I’m Ryan McGinley,” because you had already gotten such a head start. It’s weird to think about that time when we were all like, “Is Ryan going to take us?” Or, “Ryan, you’ve got to get us in.” And then we’d all destroy the party. We’d ruin it. But I remember that night because I had a real bonding experience with Dash. He was just like, “Oh, this guy’s like that?” And it was so crazy getting chased by all the models.

McGINLEY: I remember Chris Bollen, who is at Interview now and arranged this conversation. He worked at V then, and he was the first person to call who actually had my back. He was like, “Don’t worry about it. But I’ve got to know for my own sake.” And I was like, “I don’t know who that guy was. I think he came with Bruce LaBruce.”

COLEN: I’ll tell you what happened. None of us really smoked weed at that point anymore. But suddenly these people came up to Dash and me and said, “You guys have to leave. You were smoking weed. You were hanging by the bathroom.” And we were like, “No, we weren’t.” It went back and forth. They were really adamant. So we left, but we started to smash all the martini glasses.

McGINLEY: I remember I was in the bathroom and heard all these glasses break.

COLEN: That’s probably why we were lingering outside—we were waiting for you. I remember Ivana Trump was there. It was one of the first fancy parties I ever went to. Ivana Trump was wearing stilettos with diamond straps around her ankles and I don’t know why, but it suddenly felt so right smashing martini glasses everywhere. We ran out and then Dash and Agathe [Snow] started getting in this crazy fight. Dash took Agathe’s keys and threw them up on a nearby rooftop. They were fighting, so I picked up this piece of wood and was just like, “I’m gonna throw this through the window.” I dragged it a block and a half, and they were like, “No, don’t do that.” And I said, “Fuck those motherfuckers. We didn’t smoke weed. We weren’t smoking. Fuck them.” Then there was a whole male-model chase, which was the craziest thing ever—10 male models chasing me through the streets of the Meatpacking District for like 10 blocks.

McGINLEY: This leads into my next question about all of your misadventures. Talking about Ivana Trump, I feel like you’ve had so many interactions with celebrities and they’ve all been bad. Keith Richards almost tried to kill you, right?

COLEN: [laughs] I mean, I used to kind of go for it, right? Like, I’d be the one who would say, “All right, there’s Kate Moss. I’m going to try to make out with her.”

McGINLEY: And that didn’t go down well. What about Tom Ford—trying to make out with him?

COLEN: Not just trying to make out with him, but then touching his hair. He didn’t like that.

McGINLEY: That’s a no-no.

I NEVER USED to RESPECT the IMPORTANCE of a HEALTHY LIVELIHOOD. It DIDN’T OCCUR to ME to LIVE HEALTHY. I DIDN’T SEE ANY BENEFIT IN it at ALL. It WAS ALL ABOUT BREAKING, DESTROYING, and BURNING SHIT DOWN. I DIDN’T REALIZE that I WAS BURNING MYSELF DOWN. Dan Colen

COLEN: It’s such a paradox. You come from this place where you want fame; you don’t want to be bourgeois, but you want to be successful. You want to be accepted, but you also want to be going against the grain. You want to be on the outside, but you want to be on the inside. There are all these gestures that I used to go through . . .

McGINLEY: Everything and nothing.

COLEN: Everything and nothing. But it’s such an immature thing because really what you want is acceptance, and you want to pull it off in your own way. It’s almost premature to be doing things and then simultaneously as an artist illustrating them. I’m glad I was that guy rather than anyone else, but I like how I function better now—stick to my own business, do what I do.

McGINLEY: When you first moved to New York, you lived with me on 7th Street. Where was your first studio?

COLEN: I had that little studio on top of the antiques store. It was tiny—only one painting fit. I worked on the chest painting the entire time. Then I moved upstate because I couldn’t build anything in that studio.

McGINLEY: I thought you went upstate because you couldn’t focus in New York and you needed to get away from everything. Because that’s the reason I made photos outside of New York. If I had to stay in New York to do what I do, I just couldn’t do it. Too much of my concentration has been broken.

COLEN: It was about that, but it was also definitely about wanting to experiment with what happens when I go to a place where I can only work, where I have no other options. I work a lot, as you know. When we were living together, I’d come home at four in the morning and then we’d stay up until six, go to sleep, and then we’d wake up and go back to work. Some nights I’d come home at two and we’d party until six, but we always worked. I think it was really important that I ran out of space in that first studio. There was a woodshop upstate, and I could build new stretchers there.

McGINLEY: I remember you going crazy upstate.

COLEN: Yeah, I was. You know what I remember? I remember you calling to tell me about the Whitney [Museum, 2003] show. And I remember you left me a message and were like, “I’ve got something fucking crazy, man.” I was kind of going crazy already, but for two months up there it was so inspiring. I remember I was sitting in the woods and you called and said, “I got a show at the fucking Whitney!”

McGINLEY: I remember you were like, “Yeah, right.” You know, my first trip outside of the city was to come visit you upstate when A-Ron [Aaron Bondaroff] organized that van trip. I moved to New York in 1996, and that was 2002. Until that trip, I never really left New York. You couldn’t pay me to leave New York. I was so into the city. I wanted to be here every second I could. But going upstate and seeing everyone out of their element—just putting a whole group of people somewhere new and seeing what happens—was really eye-opening. That was the first time I ever used fireworks in my pictures. Dash brought those fireworks.

COLEN: Do you remember how you got me naked, and we went on the four-wheeler. That was horrible!

McGINLEY: I loved the studio you moved into after upstate—at the antiques store on Coney Island Avenue. I remember the first time I went there. They had beautiful antiques, not just junk, but pieces of art. You’d wander through the entire store with costume jewelry and lamps and vintage paintings, and then your studio would be in the back filled with all of these photo-realistic paintings that you were working on. Just having to trek all the way out there was so bizarre.

COLEN: It was almost out of some weird child fantasy movies where the door moves and you are transported to a magical world. It was fortunate for me that my grandfather had that antiques shop, and I knew I wouldn’t have to pay for a studio. But also I have to give the credit to its location. I had to go out there, and nobody would visit. And if anyone did, it was so exciting. I have vivid memories of Dash coming out there and you coming by and scooping me up at night. But those paintings [Seven Days Always Seemed Like a Bit of an Exaggeration] were about solitariness. And I never would have started that found-paintings series unless I was living amongst them in that store. That was a special place.

McGINLEY: It’s tied up with your family. Everyone always says they have a crazy family. I thought mine was pretty eccentric—until I met your family. You have the enthusiasm and intensity of your father, the eccentricity of your aunt and grandmother, and your mom kind of holds it all together. I remember the first time that I met your aunt, she pulled up in an old Mercedes, and the entire car was filled with junk, from action toys to TVs, jewelry, and scarves. There wasn’t a spare inch in that car except for the driver’s seat and the passenger seat for your grandmother. And then your grandmother got out and she was wearing a Tina Turner wig and a Robert Mapplethorpe leather-daddy hat, and her dentures were half out of her mouth. Then it struck me, “Oh, it makes sense.” The larger picture of who you are came together.

COLEN: For all the drama we all have with our families and all the tension and hostility, I couldn’t have done this without my family. Being the people that they are—they’re crazy—made it possible for me to be crazy and to live a lifestyle of my own design. They made it possible for me to walk down the street and make my own decisions every day, you know?

McGINLEY: I saw a guy on the street the other day, and he was just some random weird New York dude, and he was wearing this shirt that said I do whatever the fuck I want. That’s the best shirt I think I’ve ever seen, because I really feel like we’re so lucky to do whatever we want. That statement speaks to me in so many ways. But I can’t imagine having the dad that you have. In the sense of being an artist, he’s the greatest dad ever. I appreciate my family—

COLEN: Your family is crazy, by the way. But our families are as different kinds of crazy as possible.

McGINLEY: It’s just that I can’t talk to my family about art. It’s not their thing. But it’s amazing you have a dad who you can talk to about art in such a profound way. I was thinking of all the letters he writes you.

COLEN: He still writes me a letter every week. I can’t keep up with him. The other day he said, “I’d like to come to your studio where I could just have it to myself and sit there and take some notes.” I said, “Take notes on what?” He said, “On your paintings.” He also said, “Listen, it’s really important that when your show’s up at Gagosian I have my own time in there.” I said, “You can have as much time as you want.” Obviously he can, but you know he’s going to demand to shut everything down to get his own time in there. He got such a late start in his own art it was hard for him to make a career out of it, but thank god for me, you know? It was nice to have those discussions with him. I remember some basic art lessons he gave me early on. In high school he would show me Monet, Manet, Picasso, Matisse. But I didn’t know much beyond that. I went to college not knowing who Matthew Barney or Richard Prince was or any of this shit. My dad brought home Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly books. We were so busy skateboarding I didn’t have time to get too interested. But I remember him saying, “All these people talk about these two guys being the greatest contemporary artists. I’m not going to like them just because people say so. But I’m going to bust my ass trying to see what they see in it, because they’re getting so much out of it and I want to have the same experience.” He had the vigilance and the belief that art takes patience. It worked for him with Jasper Johns, but he never got there with Cy Twombly.

McGINLEY: My father taught me about supply and demand. We used to watch the stock market. He also used to force me to play tennis.

COLEN: Oh, my dad forces me to do a lot of fuckin’ things.

McGINLEY: Most of the e-mails I get nowadays are from students who ask me how I got my start. In truth it’s from having a really supportive family but also having a good patron who will help you—like financing all those early trips I took. When you were starting to show with Javier [in 2004], you approached him in a really businesslike way. You said, “Listen, I need money. I need you to support me, pay my rent, pay for my supplies, and in exchange I will make these paintings for a show.” I think that’s an important lesson for young people who want to be artists: You have to find someone who believes in you and who will help you find that time where you don’t have to think about a job but just making work. If I didn’t have those people in my life, I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in.

COLEN: That was some shit I learned from you—because you hustled in a very specific way. And that call I made to Javier was a really crazy call. People don’t make calls like that. But you have to go for it. You have to carve out a way to make this fucking possible for you—which has a lot to do with not having a job, right? We both needed nothing in our own way. We needed to be able to give it everything. It’s such a weird self-confidence that an artist has—to conceive of this thing that serves no function and say,

“I’m going to really work hard for it and give it and it’s just going to matter to people.” You really have to believe it all on your own. And then you need this other guy, who’s like, “Yeah! You’re gonna do it. And I’m gonna help you.” You had Jack Riley [an early patron of McGinley’s], and I had Javier. You need to be able to focus on your work. You can’t go and bust your ass at some shitty job all day and come home and try to make art . . . You gotta put all your heart into it.

McGINLEY: I remember talking to Jack Walls [artist and longtime boyfriend of Robert Mapplethorpe] at some point . . . I feel like he was our godfather and gave us a lot of advice. He said to me, “I knew that you and Dan were going to make it when you guys decided not to become barbacks.” He said, “If you’re an artist, you have to be unemployable and you only can make art.” One of the first paintings you made in college was for Jack Walls, right?

COLEN: Definitely. Jack is so important to our history. I remember making that baseball-field painting in college and getting an inkling of what I wanted to do. Then I came home that summer thinking I’d go back a lot more ready. That’s when I met Kunle [Martins] and Jack. You and I had lost contact for a period of time, and you had gone out and met all of these different people. Your life just expanded. And that’s when I found out that you were gay. [laughs]

McGINLEY: I thought you knew! And that’s when you found out!

COLEN: I feel like we were in Cherry Tavern, and I was talking about Kunle and someone said, “That guy’s gay.” I was like, “What? That’s crazy.” I was just so innocent. And I said something to you like, “What’s up with girls?” And you were like, “What are you talking about? I’m gay, man.” I said, “Wait, what?” For me it was like, Whoa, we grew up together, we were doing the same shit. We’ve come this far sharing a path that’s so similar. That was a big juncture. It was like, “If he’s gay, I might be gay. I probably am gay. What’s the difference? He’s Catholic and I’m Jewish.” Spending that whole summer hanging out, I even had that period where I wished I was gay. “This gay shit seems dope. I don’t know how to deal with girls, and these guys are all buddies, and they’re fucking, and they’re having fun.” I sweated it. But when I went back to school, I was like, “Well, I’m just this middle-class white Jewish guy.” I feel like I got plenty of things to make art about that, right? But at the time, I thought, Why can’t I make art about being gay, about being black, about identity, about all these things? And I went back to school and I made that stuff that was a weird exploration of homosexuality. They’re paintings about men. That was the first body of work I was proud of. I remember thinking, This stuff is legitimate art. I came out of school and I sold those, and for a while it kept me from having to find a job.

McGINLEY: You know that we lived together for 10 years? A decade. It’s crazy. First I lived on Bleecker Street and you used to sleep on that big yellow beanbag. And from there we lived on 7th Street together with all the things that went down there. Then eventually we shared a studio on Canal Street. That move really helped me, and that’s when business took off. So many things changed. But what I’m trying to say is that I miss hearing your feet in the morning. You dragged your feet in a certain way and I would think, Oh, Dan’s up. Now I have my own apartment with no other roommate, which has always only been you.

COLEN: If I wasn’t sleeping on 7th Street, I was sleeping at Jack’s or Dash’s—people that I met through you. I felt like you were taking care of me the whole time, showing me the ropes. I’m glad I did that one thing where I got Canal Street for us. That was my one contribution to a grounded lifestyle.

McGINLEY: What about showering? Are you showering these days?

COLEN: I’m pretty clean. I mean, so much shit has happened in the last year that it’s pretty crazy. It was a profound thing to move out from you on Canal Street because I felt like, “I’m leaving Ryan. I’ve got to figure out how to be a grown-up.” So now we live alone, but I miss so much of it . . . The relationship that roommates share—even just sharing a studio. Now I’m moving out of the studio that I share with Nate, and I’m going to be on my own in Tribeca. For a while Nate and I were trying not to leave, but it ended up happening in a really beautiful way. I’m excited about the move. I need a space to myself. My work needs it.

McGINLEY: What work are you making for the Gagosian show? What are your plans for filling up one of the largest gallery spaces in the city? Are you gonna have a skate ramp?

COLEN: Yeah, I’m gonna have a skate ramp.

McGINLEY: An upside-down one?

COLEN: Yeah, an upside-down one. But deciding and committing to do the show at Gagosian was a process of so many years.

McGINLEY: Since your bathroom show at Gagosian [Potty Mouth Potty War, 2006]. You had a show in Larry Gagosian’s bathrooms. And what’s even crazier is that he has, like, 10 bathrooms at that gallery?

COLEN: I think I used five of them.

McGINLEY: Even Wal-Mart only has one bathroom. I always liked that show. I visited it a few times, and I tried to use every bathroom that your paintings were in. That was really important to me to pee in every toilet or, like, try to take a shit in every one of them.

COLEN: I used that photograph of yours for the flyer for that show.

McGINLEY: Oh, yeah. That was a photo from Dash’s house of you peeing into my mouth.

COLEN: Yeah. But it’s funny because I didn’t meet Larry back then. Larry had no interest in getting to know me. He had no clue who I was.

McGINLEY: You never met him at the bathroom show?

COLEN: I met him the opening night. What was more exciting was that it was the opening of David Smith that night, and except for me and a few friends, no one had any clue that my bathrooms were opening. I think he just let some kid do something over there that didn’t take up space in his gallery. It’s funny all of these years later that I’m doing a show at [Gagosian] 24th Street. It took me a really long time to get comfortable with that, you know? It basically got to the point that the show I wanted to do in New York turned into this thing I couldn’t imagine doing anywhere but 24th Street.

McGINLEY: How did you go from doing all of those time-consuming candle paintings to doing the Holy Shit paintings? The paintings you had made before those were so labor intensive, taking one or two years to complete. Holy Shit has such a sense of immediacy to it. I remember thinking that sort of hanging out with Dash and all of our friends doing graffiti, that that immediate gesture of the hand might have worn off on you.

COLEN: I needed an outlet for something immediate. I made it in Paris after we all went over there. I spent two years in my studio making four paintings, and you guys were going to Paris for Agnès B., who didn’t have much interest in me. I was like, “I can’t get stuck in New York.” I said, “I have some paintings.” I just wrapped up some blank canvases and sent them over. They flew me to Paris, and me and Dash went to the hardware store. I had never even bought spray paint before. I did the Holy Shit painting in the courtyard right there. I brought it back to the studio in New York and didn’t think about it. But then I showed it to Javier, and he was psyched and brought it to Miami. Then I showed it to Neville two days before the show he was curating at Barbara Gladstone, and he put it in.

McGINLEY: Last time I saw you, you said you were going to quit smoking. Did you?

COLEN: Nate and I quit together. It’s been six weeks. We did the Allen Carr seminar, which tries to get you to understand why you smoke. And now I run and do yoga.

McGINLEY: Watching you smoke was one of the craziest things I’ve ever seen, because even though you smoked, like, two packs a day, it was like every drag was your last drag ever on the face of the earth. I’ve never seen anybody smoke like that, like you were smoking a crack pipe or something. Like you were trying to get to the last of the rock with the cigarette. It was fucking weird, man.

COLEN: My life is about deprivation right now. I felt like this was a good time to do that.

McGINLEY: So your life is a series of noes right now. Do you have some yesses in there?

COLEN: It’s everything and nothing. The noes and yesses are simultaneous. I feel differently now, and I’m excited about the project I’m working on. I’ve never been this excited about my work. McGINLEY: I’m excited that you’re alive and that you’re not dead. I thought you were going to die for so many years. Now do you feel like you’re going to live until you’re a hundred years old? I kind of feel like I will. That’s been a recent feeling.

COLEN: I wouldn’t be making this show if I were getting high right now. I’d be making a different show. I probably wouldn’t be pulling off 24th Street, but regardless, I would be making work. I don’t think it would be as good. The thing is, I never used to respect the importance of a healthy livelihood. It didn’t occur to me to live healthy. I didn’t see any benefit in it at all. It was all about breaking, destroying, and burning shit down. I didn’t realize that I was burning myself down.

McGINLEY: When I look at you now, I’m just so happy to have my friend with me, because I’ve lost so many people to heroin over the past few years. Through it all, you’ve kept your shit together with your art. You never stopped being prolific.

COLEN: So much shit has happened in the past year that I can’t really credit any one thing for the shift in my lifestyle. I found the desire to figure out how to live because I saw that my work was starting to suffer. I don’t know how I maintained my work. I let everything else fall down around it. It was the last thing standing for me. But I saw how distant it was getting, and my relationship with my work changed. The breaking point wasn’t just Dash or my health. In the end it was the way I was seeing that changed.

McGINLEY: Do you remember that intervention I organized for you? [laughs] That was really fun, man. I think I got your whole family together and all of our friends, and we all huddled in my side of the studio.

COLEN: I couldn’t believe that was happening unbeknownst to me.

McGINLEY: We were all huddling together and being like, “Okay, okay, sshhh, shut up, turn your cell phones off. Okay, is everyone ready? Is everyone ready to do this right now?” I remember looking in everyone’s eyes and staring everyone down, and I think your parents were already crying, and then I was just like, “Keep it together. We’ve got to do this,” and then, like, going into the kitchen and you just being like, “Oh my god! Seriously?”

COLEN: [laughs] Oh, my god.

McGINLEY: That was 2006.

COLEN: It was important. Obviously, I was really stubborn and not absorbing anything you guys were saying, but it resonated. It made an impact on me. I stopped doing heroin because of that intervention. I didn’t stop getting high, but I did stop using heroin six months later. It’s kind of like how I quit smoking. You get the information in your head that you don’t want in your head, and it gets stuck there—like having you guys do that. It stuck in my head, and it ruins it.

McGINLEY: You once said, “My work keeps me away from love.” I sometimes feel the same way. I feel many artists probably feel like that. What’s your interpretation of that?

COLEN: I think it’s the same way with our not having jobs . . . Basically we compromised on all the basic things that everyone else has. I think that people don’t have anything comparable to what we have with our work, except for a child or a spouse. We’ve always put our work first. And when you’re starting out, you do have to put all of your energy into it and make sure you have a place in the world, and you’re fighting to hold on to that. I needed to live how I have lived for the past 20 years to do what I do, to make what I make, to think how I think, to feel how I feel. But I’d like to experience as much as I can in my life. Love is important. I didn’t have the energy to be giving it to somebody else in a way that they deserved, and I knew that. So I’ve always been scared to go too far with somebody I care for because I knew there would come a day when I’d need to pick up and finish a painting for the next three months. That day is inevitable.

McGINLEY: Your new paintings, which include pictures of confetti, seem to me about celebration. And the idea of celebration resonates a lot in our lives as being these downtown crazy party kids and having celebratory adventures. The “hamster’s nest” that you did with Dash is definitely a celebration. The idea of fantasy and celebration are big themes in both our work.

COLEN: There’s something about the potential in confetti. There is a side that’s purely celebratory to it. In a way, those paintings could be pure abstraction. It’s lines of red and green and blue. But all of these mechanisms we have for celebrating are so double-edged. So much sorrow comes out of joy. I’m not sure where the paintings will lead, but I like the potential in them. It started when I was working with a gum painting that started to look like confetti—and it reminded me of a parade for JFK.

McGINLEY: I have a lot of remembers about you. Do you remember when I was on one of my trips and you had anal sex with a girl on my bed and there was shit on my bedsheets and I hung them up in your studio?

COLEN: Wait, those bedsheets exist somewhere . . . We could find them . . . I don’t remember, but you wrote something on them!

McGINLEY: Did you save it as a piece of art? I was so not psyched, but I wrote something really clever. What was it?

COLEN: It was so good. It was really clever, and somebody took them. I feel like Dash might’ve even . . . But there has to be a photograph of them somewhere.

McGINLEY: I also remember being with you on September 11. The night of September 10 we were out at a party at The Park for Marc Jacobs, and we stayed up getting high until 6 a.m. and then went to sleep. At 9 a.m. the buzzer was buzzing, and this librarian . . .

COLEN: I still sometimes see him in this neighborhood—

McGINLEY: He was crying. He said, “Oh, my god! The World Trade Center—a plane flew into it.” And you and I were like, “Listen, you just moved to New York. You’re from, like, Minnesota. Just chill. Shit like this happens all the time . . . ”COLEN: And then we went back to bed.

McGINLEY: But eventually we went outside, and we realized the tragedy that had happened, and we walked around. I remember being with you on the West Side Highway.

COLEN: We had our bikes.

McGINLEY: Yeah. I have a picture of it. I remember being with you on the West Side Highway and it was right after the second building had fallen, and there was an insane cloud of smoke.

COLEN: We went riding around that night with a bunch of people, and we had to snake to get closer and closer because all the streets were blocked off, and we were coming from the East Side to the center and went all the way around to try to get in from the south. And there was one fireman walking down the block covered in soot, and he was so spaced-out, like he was on another planet.

McGINLEY: In closing, I want to say that one of my favorite artworks of yours is the photograph of Garfield and his sidekick Odie in front of Stonehenge [Odie and Garfield]. I like it because it reminds me of us.

COLEN: That piece also makes me happy, in a really weird way. I always knew you liked it, but I don’t feel like too many people ever gave a shit. That work was solid, though. It holds its own. I think it’s been important in my development to have the freedom to say, “I want to put it in a frame and call it mine.”

Ryan McGinley is a New York–based artist whose most recent solo exhibition opened in the spring at Team Gallery.