What’s in the Bag: The Sculpture of Christopher Astley

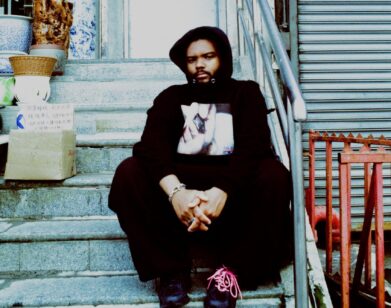

GERONIMO, 2010. COURTESY THE ARTIST

In the decade or so since sculptor Christopher Astley began working with bags and poured concrete, he’s become a connoisseur of prosaic containers. Astley loves those oversized Chinatown shoppers made of a synthetic weave (“I like the texture of them a lot—they become like canvas”); he notes the merits of plastic trash bags for how they easily they “smush” when filled with wet cement. The clear, sturdy plastic of bedding cases is another favorite material, and appears patterned with rainbow ducks in the form of a Dooney & Bourke purse in Geronimo (2010), his new show at BravinLee Programs in New York. That bag in particular was nicked from Astley’s wife, Teen Vogue editor-in-chief Amy Astley.

“She has a lot of good bags (brought home from work) that I kind of pilfer,” Astley said, at his Chelsea studio Wednesday afternoon. “She doesn’t know a lot of the time and my daughter’s always, ‘Don’t do it, Dad! She’ll find out about that one.'”

Astley casts concrete forms from bags (and on occasion, boxes) that he’s found, made and altered. Filled with wet concrete, then sometimes suspended from a forklift in Astley’s studio, the bags bulge and break; the artist then stitches them back together and paints on the resulting forms, emphasizing the points of strain.

“The bags tend to do what they want to do,” said Astley, who look to challenge the pre-planning that he says is too prevalent in large-scale outdoor sculpture. “I’m not the world’s greatest craftsman, and I don’t try to be. So because of that, things don’t work out in a predictable way and I kind of keep that. It’s important to me.”

Each form exists as a stand-alone piece, but Astley also arranges what he calls his “tough little characters” into grouped works that heighten their surprisingly human aspect. For “Geronimo,” Astley has stacked 28 forms on top of and against each other, forming a wall that resembles bodies huddled and climbing over each other. Most of the boxes and bags were originally square or rectangular in shape; the cement filler and Frankenstein re-stitching disrupts their once rigid geometry.

In a last-minute edit to Geronimo made earlier this week, as Astley was transporting the sculpture to BravinLee, he removed two forms that had given the piece its name. On one end of the wall, the two now-excised forms created a figure that had a “little leer, this little grin on its face.” On the other end, the form perched on top resembles a “cubist bull head.” Inspired by a book on the Apache leader that he’d recently read to his daughter, Astley saw in his piece an aspect of the Geronimo legend, who was said to charge into opposing throngs with just a hunting knife. Astley sees the work as a figure running from a raiding Geronimo, or Geronimo himself taking off with his bags of loot.

Astley also translates his sculptures into other media. He began making photographs and paintings of the sculptures as part of the process of thinking through the original works. Now a number of these exercises have become artworks on their own. Poster-size printed photographs of sculptural work are tacked up on the walls of Astley’s studio. The individual forms in the photograph of Groan Blind have been cut out, and each piece curls up away from the wall–a gesture which is also sculptural, Astley pointed out. He’s currently working on fitting a canvas print of Swelter (2010) into a structure, then covering it with resin and fiberglass to create a kind of “armor” that bulges out like the forms captured in the photograph.

GERONIMO OPENS TONIGHT, 6–PM. BRAVINLEE PROGRAMS IS LOCATED AT 528 WEST 26 STREET, STE 211. HE WILL THEN SHOW WORKS AT GROAN BLIND, ON VIEW IN A GROUP SHOW CURATED BY BETH DEWOODY AT SALOMON CONTEMPORARY IN EASTHAMPTON, IN JULY.