Anne Collier

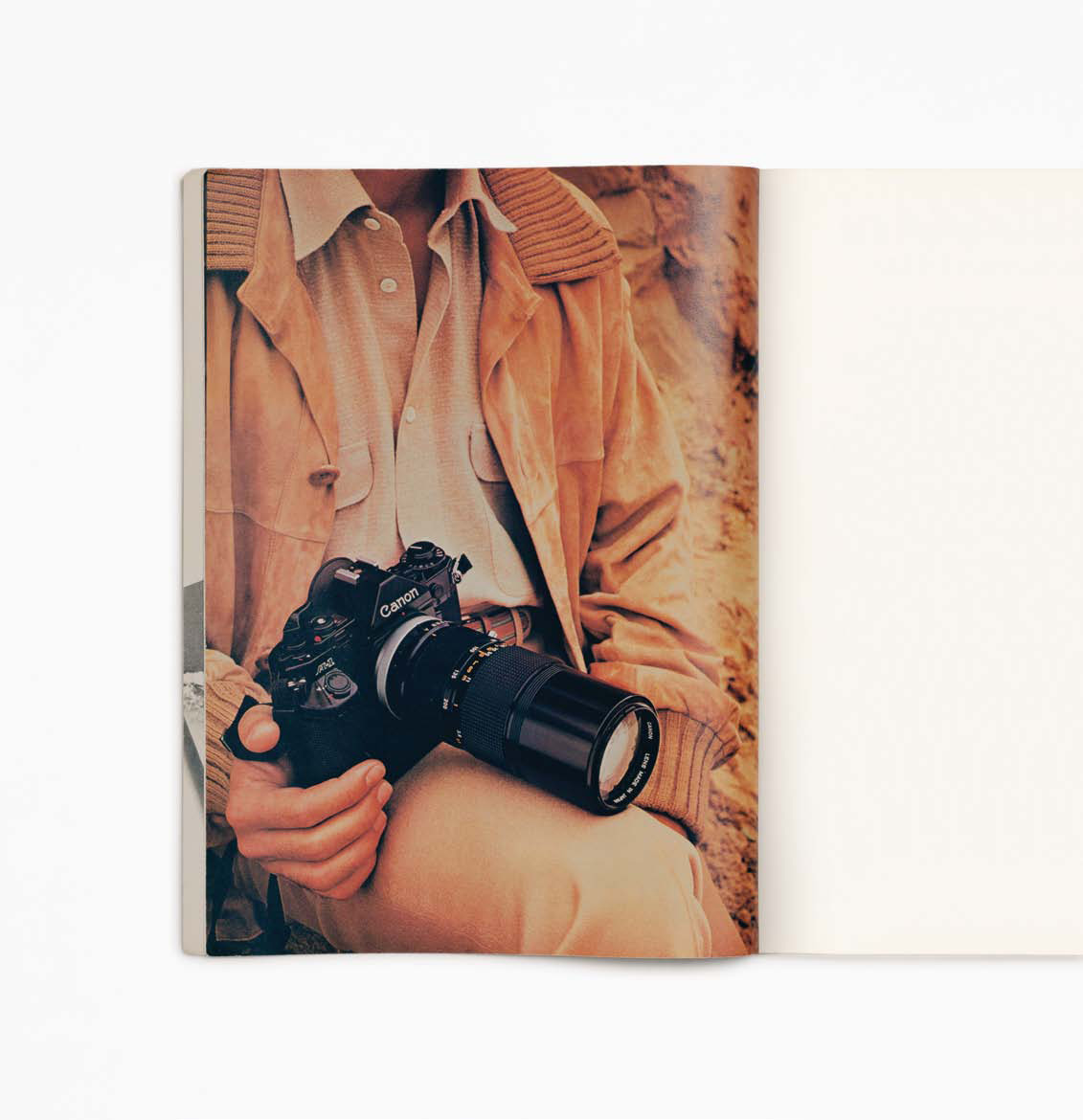

It is not a stretch to think of Anne Collier’s forensic photographic studies as excavations. Similar to the practice of an earthworks artist, Collier’s work involves digging through our cultural topsoil to uncover, reassess, and completely redirect the forgotten underlying images that inform how we’ve come to view the world. Her choice of material isn’t dirt, but it’s just as layered: old record covers, pin-up calendars, camera advertisements, fine-art nudes, pop-culture magazines, movie stills—a veritable recycling bin of mildewed 20th-century media ephemera. The 41-year-old Collier, who lives in New York, finds most of her material during record-shop or flea-market excursions, although eBay is also a reliable source. Collier typically isolates her chosen subject on a field of white paper and shoots it with her Sinar P2 4×5. Often, the still lifes maintain their bindings, ragged pages, or Post-it markers. Collier has a clear predilection for images that revolve around women, cameras, or some formulation of both. When asked why many of her sources are infused with a 1970s aura, Collier says, “The ’70s are interesting in terms of the moment when photography was being recognized as fine art. And artists like Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler were doing brilliant work. At the same time, in photography magazines, there is this casually sexist imagery about women and cameras.”

While Collier doesn’t think of her latest studies as autobiographical, and insists on their classification as still-life photography, theoretical collisions abound inside her quiet white frames: Her lucid, formalistic approach to shooting the material masks the highly subjective selection process; the use of discarded imagery created for a male audience gets rerouted as a double agent of feminist critique; Collier’s eye becomes the authorial eye, and the salvaged pop imagery exists almost as its own ghost or residue once its initial purpose has been lost to time. For her solo show at New York’s Anton Kern Gallery this month, Collier is presenting new work—including a series of 1960s travel postcards and shots of a female nude playing backdrop to camera reviews in a magazine (a Pentax K2 is described as a “bayonet” very close to the genital region). Nothing here has been taken out of context. In fact, it’s Collier’s careful preservation of context that keeps these subjects floating in a photographic purgatory—neither doomed nor completely saved, they await our judgment.